This idea comes from Suzanne East, who I saw teach a great Year 12 Biology lesson this week. She told the story of when her son, Ted, dropped an entire box of peppercorns. To add extra impact, she proceeded to enact this with a large box of beads. Needless to say, they spread everywhere, much to the shock of the students. Of course, my summary of this lacks the real humour and panache with which this unfolded. However, this story was the starting point of much debate about whether or not this story acted as a reasonable model for the process of diffusion, or not. Their discussion was filled with scientific terminology and deep thought.

Suzanne’s anecdote about Ted used the principle that learning about complex ideas is itself a bit like understanding a story. Stories are not just for literary narratives but can be used to illustrate even the most complex and abstract concepts (e.g., math and science).

I really liked the process of Suzanne’s storytelling, because apart from being memorable, personal and fun, as a teaching and learning technique storytelling can:

- Organise information, developing a student’s schema and clear network of ideas;

- Incorporate cause and effect, helping students to consider causal links and thus aid memory;

- Have impact and therefore facilitate remembering;

- Enhance discussion and debate;

- Promote problem posing and problem solving.

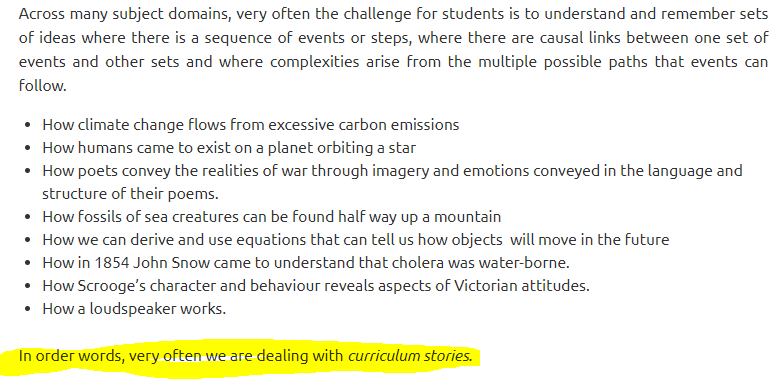

Here is a screenshot from Tom Sherrington’s blog ‘Great Teaching. The Power of Stories’ about this:

Tom Sherrington goes on to link to a video by Brian Cox, who is a master storyteller when he is explaining the workings of the universe. He weaves narratives, rather than starting with facts… just like Suzanne at the start of her lesson.

What stories could you tell?