Ian Richardson, Head of Computer Science, explores the value of leading student expeditions, and identifies how the adults leaders involved can catalyse the often life-changing benefits for students

For many years of my career, Marrakech has held a special place in my heart. I have loved accompanying students as they lead on through the chaotic noise and bustle of the Jemaa el-Fnaa, overcoming initial hesitancy to ‘master’ the art of bartering, and somehow managing to navigate their way around the maze-like multitude of ancient streets and passages. With the prospect of another expedition this October, I have been reflecting on how the adult leadership team maximises the impact of these personal development experiences.

What are the benefits of expeditions?

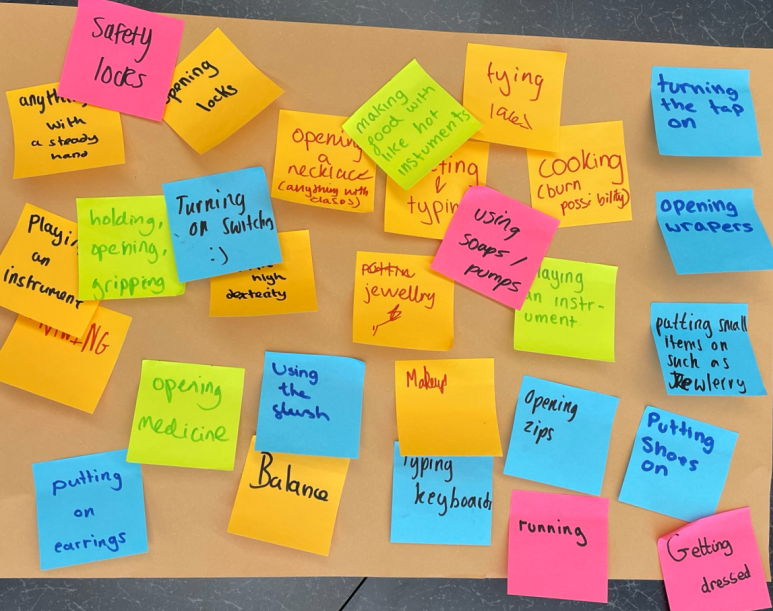

In order to understand the personal qualities of good expedition leadership, it is important first to consider why we take our students on expedition. In a review of current research into the impact of outdoor education on individuals, Heather Prince lists seven different themes for personal development of individuals on outdoor residential experiences[1]:

- Confidence

- Teamwork

- Life skills

- Intra-personal skills

- Independence

- Aspirations

- New opportunities/activities

Having accompanied various expeditions in my career, I have seen pupils’ personal development first-hand. Whether I have been on a Duke of Edinburgh’s Award expedition over four days, or an overseas expedition for a week, or a month, as teachers we are granted the privilege of watching our pupils “grow up” in a short space of time.

What personal skills do teachers need?

- Flexible thinking and embracing experiences: As teachers, we may have experience of educational visits, whichrun to fairly strict itineraries. However, successful expeditions are conducted more flexibly, with students taking control of parts of the itinerary. Accompanying adults should be comfortable in adapting plans and assessing risk dynamically to ensure safety. Often the most memorable experiences on expedition are those which the students discover by themselves unexpectedly. Accompanying staff are often asked to step outside their comfort zone and to embrace new experiences (memories of discomfort in taking part in traditional dancing in Borneo spring to mind): it is important that staff lead the way and participate in the experiences on offer, making it easier in turn for the students to follow.

- Control and decision-making: Over the course of an expedition, the role of the accompanying adult changes. At the start, leader input is frequent and directive; by the end, the student team should be functioning with little or no input from leaders. To return to the example of the busy markets of Marrakech, it can feel strange at first to turn to a group of pupils and ask them where they are taking you. Leaders should establish appropriate boundaries to ensure safety and allow the team freedom within those constraints. Empowering participants to make decisions is what makes the expedition such a powerful personal development experience and helps to develop teamwork skills.

- Cultural understanding: Whilst acknowledging the benefits of expedition for the participants, leaders need to be aware of and sensitive to the culture of the destination. This is true in both the more practical sense of keeping the team safe, acknowledging local customs and allowing team members to communicate, and in the sense of carefully selecting the lens through which our students view the country they are visiting. For example, for expedition in October, I have invited our pupils to learn from a muezzin what it means to give the adhan (call to prayer) and how it is performed. In this way, we can allow young people the chance to understand others with empathy and avoid imposing their own values on another’s culture.

- Empathy, understanding and authenticity: First and foremost, an expedition environment is one of challenge. Both the participants and leaders are challenged in different ways at different times in the journey. Young people may find the isolation of working in a team in a remote location difficult, whilst others are challenged by busy urban areas. At times, the teacher may be challenged. A good leader will acknowledge discomfort as an opportunity for growth and support all participants by creating safe space for reflection. Valuable opportunities arise to lead through vulnerability and to model resilience.

Conclusion

Following

the restrictions imposed on all of us through 2020 and 2021, we once again have

the chance to enrich the lives of our students through travel. Although only for

a relatively short period, an expedition can have a huge impact on everyone

involved and it is a real delight to be able to share a love for travel with

students once again. By developing the skills above, an effective leadership

team can take the expedition experience to a new level and maximise the

opportunities for development.

[1] Prince, H.E., 2020. The lasting impacts of outdoor adventure residential experiences on young people. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 21 (3). pp. 261-276.