Ms Jenny Cox, Director of Co-curricular and Partnerships considers ‘School life outside the curriculum, is it important?’

“I need 3 A*’s to get to where I want to be. That means more focus on work less time on other things.”

I’m sure we have all heard this or possibly said this at some time in our lives, particularly when we feel under pressure. I’m pleased to say that Wimbledon High bucks the trend with the approach that promotes work, work, and more work, as being the key to success. We see the drive to achievement as a more rounded and fulfilling experience. However, is everyone convinced of this?

Anxiety, self-confidence, motivation and concentration can play a huge role in our mind during day-to-day life. How we choose to deal with these can affect our well-being and our ability to function effectively. Cognitive anxiety can exhibit itself as Fuzzy Head Anxiety, sometimes also known as Brain fog anxiety, which can occur when a person feels so anxious, they have difficulty concentrating or thinking clearly. At times, high somatic anxiety can lead to sickness, upset and a lack of appetite. Whilst it is normal to experience occasional cognitive and somatic anxiety, especially during times of high stress, it important to have strategies to help us lift ourselves out of this, as the worries about grades, about covid and about not being good enough, are all very real concerns as we ease ourselves back into ‘normal’ life.

Look beyond yourself

It has long been acknowledged that acts of generosity raise levels of happiness and emotional well-being, giving charitable people a pleasant feeling known, as a “warm glow.”

In the Medical News Today, Maria Cohut (2017) wrote an article on how ‘Generosity makes you happier’. She reported on a study of forty-eight people, all of whom were allocated a sum of money on a weekly basis for four weeks. In short, one group were asked to spend the money and the other group asked to make public pledges and all participants were asked to report their level of happiness both at the beginning and at the end of the experiment. The results found that all participants who had performed, or had been willing to perform, an act of generosity – no matter how small – viewed themselves as happier at the end of the experiment. It is studies like this, alongside others, that convince us that our partnership and charities work, so heavily and generously invested in by our students, is vital to maintaining a sense of perspective and our sense of well-being.

Work hard and play hard

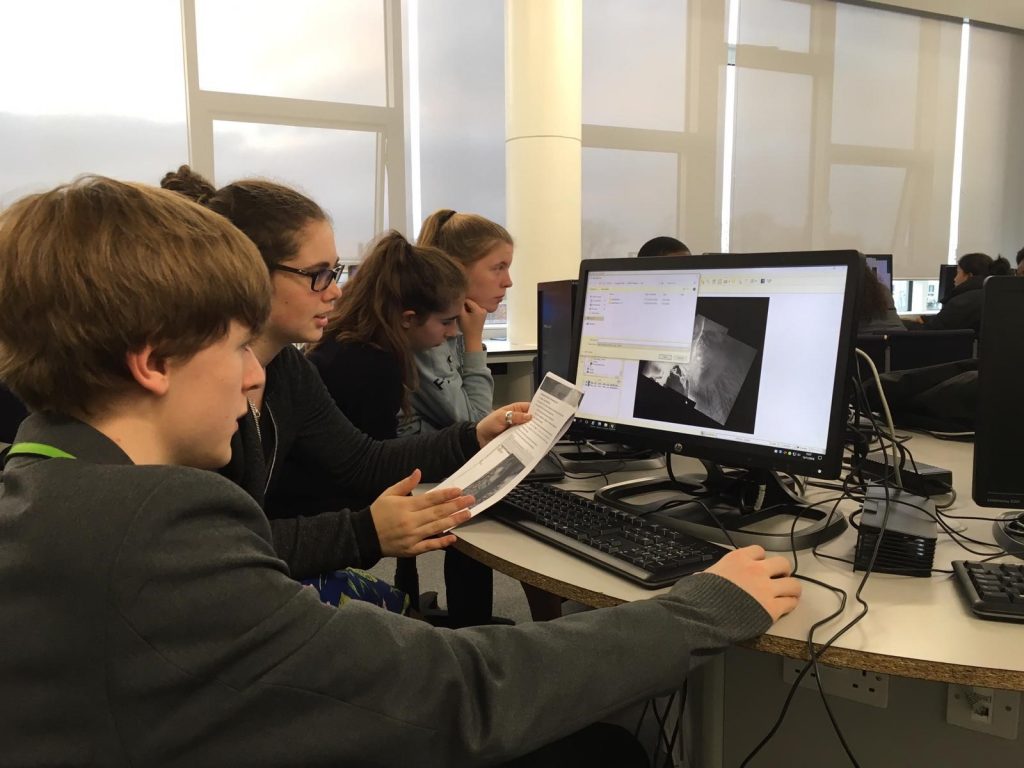

In 2020, 98% of the top ten highest achievers in Years 7, 8 and 9 at Wimbledon High took part in at least five sessions of co-curricular activities per week; is this a coincidence? Previous research has also revealed positive and significant relationships between higher physical activity and greater academic achievement (Chih and Chen 2011; Bailey 2006; Chomitz, Slining, McGowan, Mitchell, Dawson, and Hacker, 2009). There are a multitude of benefits to taking part in a balanced programme of co-curricular activities. Whether they are in school or externally organised, both appear to be hugely beneficial.

All the feelings of immersing yourself in the activities you love will again enhance feelings of well-being and start to reduce levels of stress, should they be high. The well documented moments of Flow (Csikszentmihalyi, Harper and Row, 1990) refer to those times when people report feelings of concentration and deep enjoyment. These moments maybe found on the hockey pitch, in orchestra, chess club, debating, GeogOn, Femigineers, whatever is your passion. Investigations have revealed that what makes the experience genuinely satisfying is a state of consciousness; a state of concentration so focused that it amounts to absolute absorption in an activity. People typically feel strong, alert, in effortless control, unselfconscious, and at the peak of their abilities. Both a sense of time and emotional problems seem to disappear, and there is an exhilarating feeling of wholeness. This can be controlled, and not just left to chance, by setting ourselves challenges – tasks that are neither too difficult nor too simple for our abilities. With such goals, we learn to order the information that enters our consciousness and thereby improve the quality of our lives.

Life outside the curriculum, is it important?

Evidence seems to point in the direction that a well-planned and attainable life outside the curriculum will enhance academic studies, promote feelings of well-being, and give a sense of perspective on day-to-day anxieties. Having said this, we have decided to research this ourselves. Look out for the opportunity to be part of a piece of research later this year, conducted by Ms Coutts-Wood and I, where we shall dig deeper into life at Wimbledon High. Specifically, we will be investigating the impact of our co-curricular and partnership programmes on academic progress and well-being.

References:

- Csikzentmihaly, M. 1990. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience, Harper & Row

- Bailey, R. 2006. Physical education and sport in schools: A review of benefits and outcomes. Journal of School Health, Vol. 76, No. 8.

- Chih, C.H. and Chen, J. 2011. The Relationship between Physical Education Performance, Fitness Tests and Academic Achievement in Elementary School. The International Journal of Sport and Society, Vol. 2, No.1.

- Chomitz, V.R., Slining, M.M., McGowan, R.J., Mitchell, S.E., Dawson, G.F., Hacker, K.A. 2009. Is there a relationship between physical fitness and academic achievement? Positive results from public school children in the Northeastern United States. Journal of School Health, Vol. 79 Issue 1, P30.

- Cohut, Maria. 2017. Medical News Today ‘Generosity makes you happier’