Director of Studies, Suzy Pett, discusses how the WHS English Department has started to decolonise the curriculum, including introducing a new A Level unit on postcolonial writers.

Rallying cries to decolonise the curriculum have been building for a while now. It is one of the most important conversations in education today and our recent alumnae have been vocal about it.

In a 2018 interview for Varsity magazine, Wimbledon High alumna, Mariam Abdel-Razek, speaks about her experience studying English at Cambridge. She says that, “sometimes it feels like I can’t be heard unless I’m shouting.”[1] In 2020, recent alumna, Nida, set up Wimbledon High’s first POCSOC (People of Colour Society). However, she emphasises that discussions need to be built into the curriculum, otherwise the “the burden is placed on the students of colour in schools to lead the conversations.” And, in a 2020 podcast at Oxford University, alumna Afua Hirsch raises the need to “[disrupt] the racket of positioning anything non-European as alternate”[2] as she discusses the role of the curriculum in structuring alternate worldviews and knowledges.

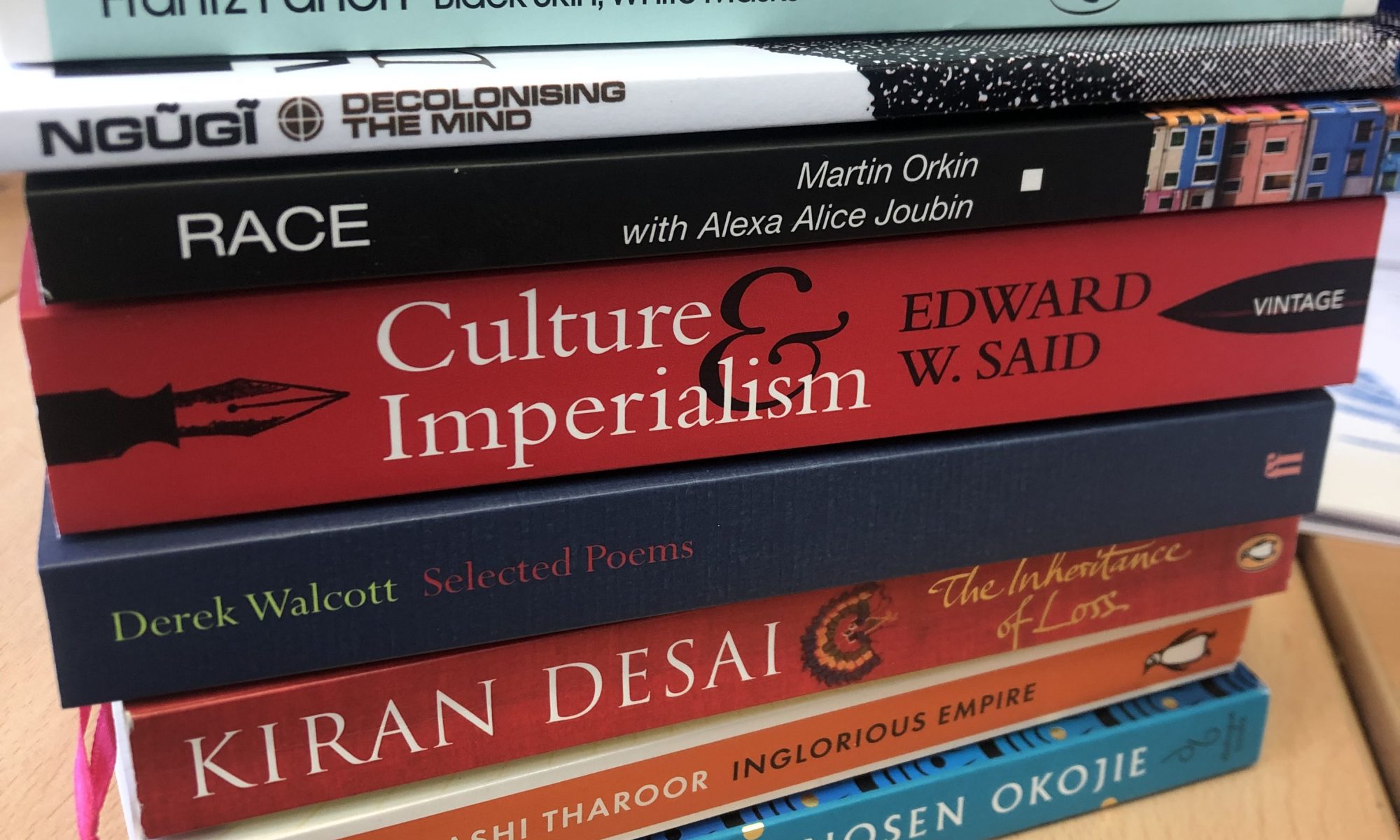

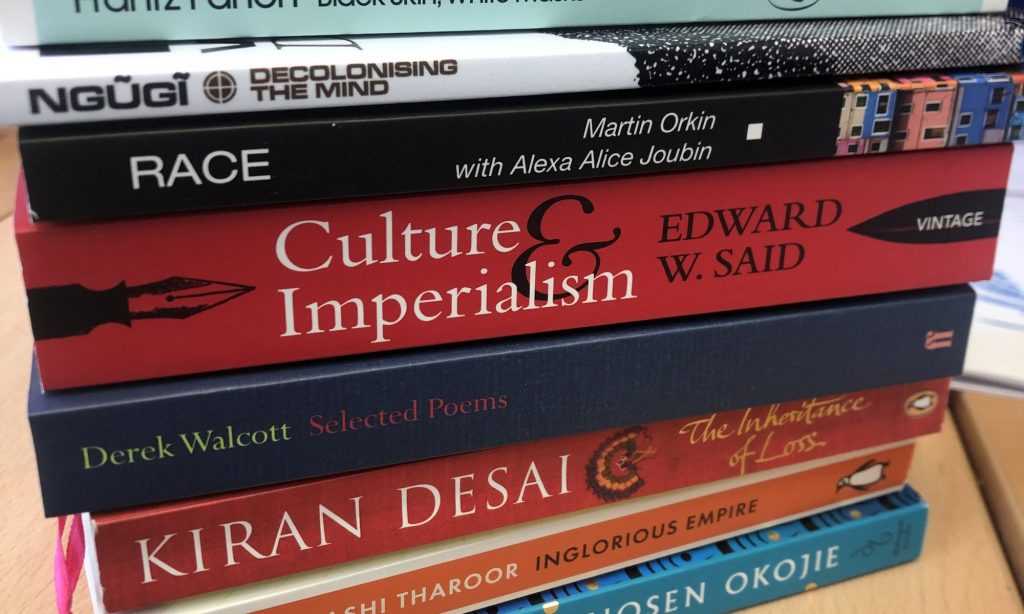

Alert to this vital dialogue and convinced of the necessity to make change, the English Department at Wimbledon High wanted to rethink the A Level course, among other elements of the curriculum. Our new postcolonial coursework unit explores the writers Kiran Desai and Derek Walcott. We are excited by the way our politically savvy students will respond and the impact it might have for them both as readers and citizens of the 21st century. The course carries with it weighty concerns that couldn’t be more important to our lives today: politics of power; societal alienation; belonging and dislocation; migration; diaspora; and identity. These are a complex nexus of issues that resonate for all of us in our lived experiences. This is a course that extends far beyond the A Level classroom, and as English teachers, that fill us with excitement and, to be honest, some nerves.

Our new course has been a year in the making. So, how have we gone about it and what are the issues at the front of our minds when teaching postcolonial literature?

- Naming the course

Whilst we are referring to our unit as ‘postcolonial’, this is a controversial term. Some suggest that it implies we have moved beyond colonialism, when clearly this is far from the case. Keen to learn from other educators, we set up a Zoom call with teachers in US. We heard it was for this reason that they had renamed their course ‘de-colonial literature.’ However, for us this is equally problematic. It seeks to politicise texts by non-white authors by positioning them as ‘writing back’ against colonial oppression. It risks distracting from the other aesthetic or experimental modes important to an author. Certainly, this was the view expressed by the brilliant writer Irenosen Okojie, who spoke candidly to our Year 12s and 13s last year about her experience as a black author. Alumna, Nida Ahmed, also suggested that the term ‘postcolonial’ risks singling out these groups of writers, signalling that they are ‘alternate’ to ‘official’ literature. Of course, these debates are all useful to have with our students. We are using ‘postcolonial’ not to imply that colonialism is a ‘completed’ act of the past. Nor does it suggest that the only intention of this literature and our reading of it is socio-political decolonising.

- Interrogating our own default settings: Unpacking our own ‘ways of reading’ the world/texts

As John McLeod writes, “the act of reading in postcolonial contexts is by no means a neutral activity. How we read is just as important as what we read.”[3] As individuals, we need to unpack how we are approaching the texts. If you think you are approaching the texts from a ‘neutral’ perspective, then you are aligned with the dominant white culture. This approach to literature maps onto our approach to ‘reading’ our world. Understanding our ‘default settings’ to texts and life is important, and so revisiting our own identities throughout the course is essential if our reading practices “are to contribute to the contestation of colonial discourses.”[4]

- Risks of intellectualising lived experiences

We were interested to read the article of Edinburgh lecturer, Michelle Keown, who works in a similar socio-economic environment to Wimbledon High. She warns that in a predominantly white context, reading about other cultures could become “a form of intellectual or cultural tourism.” The risk is that students use the texts “to learn more about other cultures, which bespeaks well-meaning, liberal sentiments, but also the highly problematic assumption that one can gain knowledge of a culture by reading [fiction].”[5] To avoid this, we will be asking students to actively engage self-reflexively with the complex racial problems seen in the texts: How do those social problems manifest within their own circle of social connections? Students need to engage with their immediate contexts. We do not want to “tinker around the edges” in our teaching of postcolonial fiction with students “[failing] to really connect with racism as something that impacts them.”[6] For us, it is important in our reading of postcolonial fiction that, through self-reflexive thought and criticism, the social problems are relocated from “over there” to “here”.

The power of this course is undeniable.

It involves a radical rethinking of our teaching practices and raises

far-reaching questions about what it means to ‘read’ English literature. We’re

intending to be bold and disruptive. In self-consciously re-examining how we ‘read’

literature, we are re-examining how we ‘read’ the world. By understanding the complex

relationship between text-reader-author, we can similarly hope to better

understand the complexities of our lived relationships.

[1] J. Chan, ‘Rethinking the canon: the burdens of representation’. Varsity, 16 November 2018, https://www.varsity.co.uk/features/16578

[2] Discussion: How does a curriculum introduce and structure alternate worldviews and knowledges? [online podcast initially held at TORCH], University of Oxford Podcasts, February 2019, http://podcasts.ox.ac.uk/discussion-how-does-curriculum-introduce-and-structure-alternate-worldviews-and-knowledges

[3] J. McLeod, Beginning Postcolonialism, Manchester University Press, 2000, p. 33

[4] McLeod, p. 34

[5] E. Denevi and N Paston, ‘Helping Whites Develop Anti-Racist Identities’, Multicultural Education, vol. 14, no. 2, 2006, p.70

[6] M. Keown, ‘Teaching Postcolonial Literature in an Elite University: An Edinburgh Lecturer’s Perspective’, Journal of Feminist Scholarship, 7 (Fall), 2015, p.103