Mr James Porter, Specialist English teacher and Experientia Scholarship lead, reflects on the first half-term of a radical bespoke curriculum project that aims to introduce the Upper Junior School girls to the concept of critical thinking and the art of Socratic discussion.

What does academic achievement look like in 2020?

Fionnuala Kennedy, Head, began this academic term with an address to staff in which she spoke of a ‘new epoch’ in education. In this time of truly unprecedented crisis the core business of schools has very much been thrust into the public spotlight, and, with circumstances necessitating a ‘back to basics’ approach, there is now a very prescient need to look closely at the fundamentals of teaching and learning and to ask – how can we do the basics better?

Nationally and globally, the lives of children have been turned upside down and the education community has been rocked by profound and severe crises, the implications of which many observers hold will be felt for years, if not indefinitely. Take this summer’s public exam fiasco and the ongoing uncertainty around this type of assessment as just one example of the domino-like impact that the COVID crisis will continue to have on the core components of the British education system. Naturally, this is leading to a renewed impetus in the search for change.

The need to explicitly address the social implications of the crisis in school planning is widely acknowledged. It is this principle that Barry Carpenter makes central in his proposal for a ‘recovery curriculum’ model for the Autumn term, which addresses the holistic development of pupils in response to a deficit that is perceived as having emerged during the period of school closure. [1]

However, there are those who propose that times of profound uncertainty be met with more divergent thinking that is far broader and deeper in scope:

In more turbulent times, a radical vision of education may emerge from cultural trauma, as it did in Reggio Emilia in northern Italy at the conclusion of the Second World War. A whole society pulled together in revulsion at the ease with which they had embraced, or tolerated, fascism, and vowed to raise young people who would not make the same mistakes. [2]

Further, a growing discourse in British education reflecting a broad spectrum of society has seen this crisis as the catalyst for their calls to end what they perceive to be an inherently problematic public assessment regime, the most eloquent of these coming from Michael Rosen in a letter to Gavin Williamson published in The Guardian. [3] Their calls to replace GCSEs with alternative models cite the established practices at Bedales School who introduced “richer, more expansive courses” that “encourage creativity, autonomy, and enjoyment of learning for its own sake” as a ground-breaking example of a successful alternative. [4]

While some have drawn equivalents, I am not comparing the gravity of our present situation with the fall of Fascism at the end of the Second World War (this weekend’s election result not withstanding). However, at no time since the Second World War has it been more important that we support the holistic development and emotional intelligence of our pupils through considerate planning that addresses emerging needs while focusing on the development of skills and maintaining disciplined academic rigour.

What is the Experientia Scholarship?

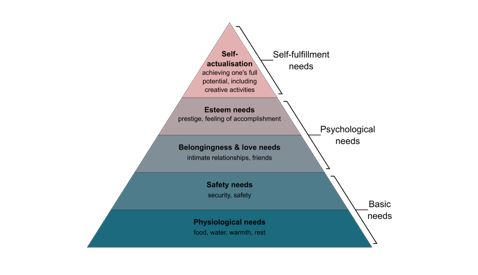

Inspired by dramatic developments in education and tasked with developing a radical new curriculum programme in the Upper Junior School, I wanted to address the challenges of 2020 and beyond by creating a programme focused on rigorous academic pursuit and the development of higher-order thinking. The programme also needed to be responsive to the needs of pupils through engaging, thoughtful, and sensitive planning that makes the habits of effective discussion and learning explicit, building on the psychological development model proposed by Abraham Maslow in 1943:

Since September, the girls in the Upper Junior School have been immersed in a bespoke curriculum programme which considers the contentious issues that affect our daily lives and introduces pupils to the concept of critical thinking and the art of Socratic discussion.

The Experientia Scholarship, which forms part of the weekly timetable for all girls in Years 3-6, exposes pupils to a range of learning experiences which challenge their view of the world. Comprising of a range of short courses, pupils explore elements of both classical ‘enlightenment’ and progressive ‘modernist’ units of study devised to grow cultural capital, cultivate divergent thinking and enhance preparation for success in a globalised and digital world.[5]

Underpinning this are three pillars which guide the ongoing development of the programme:

- Academia: A community concerned with the pursuit of knowledge, always seeking to find truth and assessing all available evidence to make logical conclusions that are not based on opinions or emotions;

- Fraternity: A feeling of friendship and support within our community, being kind and supportive, understanding that we never discount the person; we challenge their conclusions based on our understanding of the evidence;

- Culture: We learn about, respect and show tolerance towards all no matter their background, geography or beliefs. Understanding that high culture is not limited to high art, we embrace eclectic tastes across a broad range of disciplines, from Schubert to Stormzy.

Through weekly Socratic discussions based on a thought-provoking reading, pupils engage with a cycle of themes that introduce them to a range of critical topics.

| Experientia Scholarship – Autumn Term | |

| Year 3 | Has technology made life easier? Can machines replace human beings? |

| Year 4 | Does Hollywood need to change? Who makes the news? |

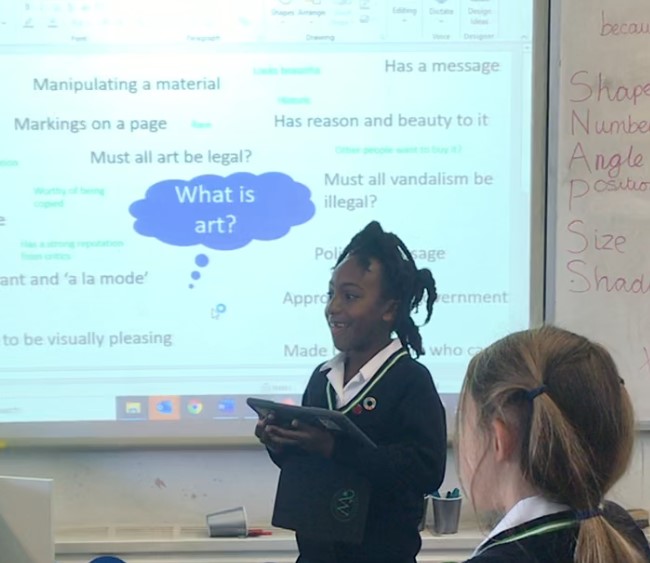

| Year 5 | What is art? Is art inclusive? |

| Year 6 | How much influence does the media have? |

The pupils reflect on their position throughout the discussion cycle and are encouraged to conduct their own research into the topics of discussion and to set their own questions for future discussions.

In the lessons, the teacher prepares discussion-based activities that ask a series of open-ended questions specifically targeting the different ways of thinking about a topic. Arguments are dismantled into their constituent parts which can then be evaluated, and the implications considered.

The benefits of the Socratic approach to learning have long been espoused by those who have studied it:

“[…]Within the context of the discussion, students listen closely to the comments of others, thinking critically for themselves, and articulate their own thoughts and their responses to the thoughts of others. They learn to work cooperatively and to question intelligently and civilly” [6]

The scholarship culminates in a formally assessed public speaking activity in which pupils explain and justify their thinking around the topic of their choice before being awarded commended, highly commended or distinction, aiming to reward metacognition and the process of learning rather than just linear attainment.

What have the lessons been like?

I will share one example of the impact that I have observed of the Socratic approach with a Year 4 group.

The first discussion in the Year 4 unit on ‘who makes the news?’ is an introduction to the concept of fake news and an examination of the people who could gain from spreading misinformation. In a follow-up discussion, pupils look at the idea of censorship and consider the occasions when they believe it is justified before reading a text about president Xi Jinping who, it is reported, censored Winnie the Pooh in China after memes emerging online mocking supposed similarities between them offended him.

The girls had decided that there are circumstances in which censorship is warranted. They gave the examples of internet blocking on their devices at school and people sending offensive messages as times when it would be right to censor. I was fascinated when the implications of their reasoning were applied to the example of Xi Jinping. While there was broad agreement that offensive communication should be censored, a vocal group of girls emerged who came to the conclusion that presidents, being in a unique position of influence and power, were to be treated differently than the general population, and in this case the rights for the people to criticise the president should be defended.

The ability of the girls to form critical connections when introduced to reasoning in this way was powerfully illustrated to me recently with the same group while watching Newsround coverage of Trump contesting the presidential election count. Pupils were immediately able to identify this as misinformation, and crucially were able to articulate the motivation for Trump to do so, as well as identifying the dangerous implications.

Teachers from across the Junior School have also commented on the impact they have noticed the Scholarship having in other areas of the curriculum. In an English lesson, Year 5 girls were able to articulate their thoughts around intrinsic gender bias and the etymology of words, citing the example of ‘female’ being the negative form of ‘male’, and explaining that this issue had been thrown up in discussion with Mrs Walles-Brown about whether art is inclusive.

I asked the girls to share their thoughts describing what their Experientia lessons have been like. This word cloud formed from their responses neatly summarises the general consensus felt after the first half term of the Experientia Scholarship in the Upper Junior School.

Further Reading

Carpenter, B., A Recovery Curriculum: Loss and Life for our children and schools post pandemic, Evidence For Learning [online], 2020, https://www.evidenceforlearning.net/recoverycurriculum/

Israel, E., “Examining Multiple Perspectives in Literature.” In Inquiry and the Literary Text: Constructing Discussions in the English Classroom, NCTE, 2002

McConville, A., Bedales: Rethinking Assessment [online], 2020, https://bigeducation.org/rethinking-blogs/bedales-rethinking-assessment-a-case-study/

Rosen, M., Dear Gavin Williamson, here’s how to avoid more exam catastrophes, The Guardian [online], 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/sep/29/dear-gavin-williamson-heres-how-to-avoid-more-exam-catastrophes

Wells, G., and Claxton, G., Learning for Life in the 21st Century, Sociocultural Perspectives on the Future of Education, Blackwell, London, 2002

References

[1]Carpenter, B., A Recovery Curriculum: Loss and Life for our children and schools post pandemic, Evidence For Learning [online], 2020, https://www.evidenceforlearning.net/recoverycurriculum/

[2] Wells, G., and Claxton, G., Learning for Life in the 21st Century, Sociocultural Perspectives on the Future of Education, Blackwell, London, 2002,

[3] Rosen, M., Dear Gavin Williamson, here’s how to avoid more exam catastrophes, The Guardian [online], 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/sep/29/dear-gavin-williamson-heres-how-to-avoid-more-exam-catastrophes

[4] McConville, A., Bedales: Rethinking Assessment [online], 2020, https://bigeducation.org/rethinking-blogs/bedales-rethinking-assessment-a-case-study/

[5] Boyd, C., Experientia Vision Statement, Wimbledon High Junior School, 2020

[6] Israel, E., “Examining Multiple Perspectives in Literature.” In Inquiry and the Literary Text: Constructing Discussions in the English Classroom, NCTE, 2002

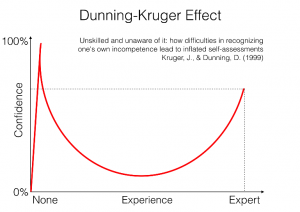

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If we consider the Dunning-Kruger effect (demonstrated on the diagram to the right) we might agree. The principle is that ‘knowledge without sufficient experience can lead to an overestimation of ability’. It is no surprise that Donald Trump has been nicknamed the ‘Dunning-Kruger President’ in articles by the New York Times, Bloomberg, and the Independent. I recall an interview where he tries to explain uranium to his audience:

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If we consider the Dunning-Kruger effect (demonstrated on the diagram to the right) we might agree. The principle is that ‘knowledge without sufficient experience can lead to an overestimation of ability’. It is no surprise that Donald Trump has been nicknamed the ‘Dunning-Kruger President’ in articles by the New York Times, Bloomberg, and the Independent. I recall an interview where he tries to explain uranium to his audience: