Isabelle, Lauren, Olivia and Homare (the WHS Social Robots team) describe how they are working on using the school’s social robots Bit and Byte as reading buddies in the Junior School, and update us on the progress made so far.

We are the Social Robots team, and we would love to present our project, which is robot reading buddies, to you. This club started in 2018 and we work with the 2 robots which we have at school. Since then, we have taken part in competitions (such as the Institut de Francais’ Night of Ideas competition[1] – which we won!) and other projects and challenges within the school. Currently, we have been working on how we could use these robots in the Junior School to help encourage reading practise.

What we want to achieve and how

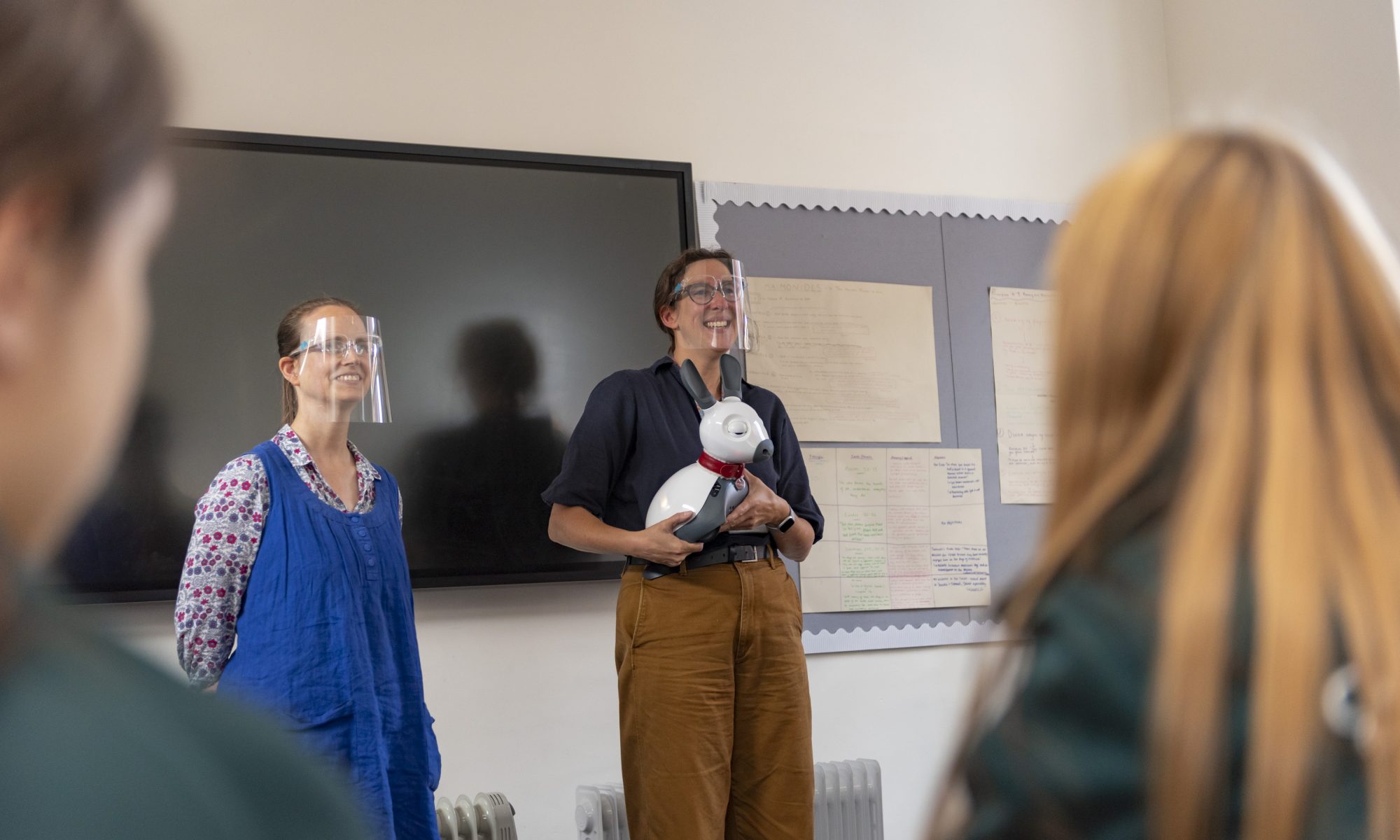

At Wimbledon High School we are lucky enough to have two Miro-E robots. They are social robots meaning they can react to touch, noise and other actions due to the sensors and cameras that they have. We can then code the robots into changing colours, wagging its tail, pricking up its ears and many other possibilities! The Miro-E robots are designed to mimic a pet. But we are not the only one’s coding Miro-E robots for a social cause: they are also used for the elderly to combat loneliness.[2] We hope they will have a similar calming effect on children.

We all know how important it is to learn how to read since it broadens knowledge and vocabulary, as well as opening doors for future learning; therefore, we want to include the Miro-E robots in the Junior School as reading buddies. In addition, reading improves presentation skills and develops confidence and independence. Enjoying reading from an early age will help to support these skills.

To encourage this crucial development in the child’s life, we believe that it is vital to make those learning to read feel comfortable and stimulated. As a social robotics team, we realised that one way to achieve this was by creating a robot reading buddy that helps young children at school to practise reading whilst also being motivated by a cute robot dog (cat, kangaroo, cow, bunny, or whatever animals you think the robots resemble)! If we can compel children to read with our social robots, as well as to teachers or parents, this might change the amount they read or the difficulty of the books they attempt; therefore increasing the speed of reading development, as it is encouraging in a non-judgmental environment.

Our research about reading buddies

Research has shown that it is beneficial for children who are learning to read to have a companion who just listens, rather than correcting them, as we know that reading can be a challenging and sometimes daunting experience for some students. Of course, it is equally important for a teacher to help the child when reading and correcting them so that they can learn and improve. But we also think it is crucial for children to enjoy the reading experience, so that they have the motivation to keep learning.

Therefore, Miro-E robots are perfect for this job as they can help find the balance between learning to read, and practising to read. Also, we can code the robot to adapt to the situation and make the reading experience the best it can be. As we have 2 of these robots at the school, it will also enable the Junior Staff to have multiple reading sessions at once. Finally, as we mentioned, the robots can react with sounds, movement, and lights which we are hoping will engage the students and keep the experience enjoyable.

While researching, we did also find many studies and papers regarding the effects of animals such as dogs on learning. However, we found little about robotics and coding to achieve the task we set out to complete, making it no mean feat. As school-aged children ourselves, what we are trying to do is pioneering and exciting but also has its challenges. We look forward to introducing Bit and Byte to the Junior pupils and inspiring them to get involved, not only with reading but also to get them excited about robotics and coding!

Our progress so far

We have been working on this project since the start of 2021, and we have been focussing on research, as well as some coding. At first, we had a discussion with some Junior School pupils, and we sent a survey to parents to see what their top priorities would be for the reading buddy and what their opinions were. We find it really important that the users of the robot reading buddy can contribute their ideas and opinions so that the reading buddies are as beneficial for them as possible.

An example of these results is that both the students and the parents wanted the robot to guide the child through nodding. Because of this, we set up 5 key stages of the reading process, with different coding programs (and therefore different emotions and actions shown in the robot) for each. We have coded these 5 key stages separately already. These stages are:

- Starting to read, so when the students have just started their reading session or when they continue after a break. We have coded this to have an excited emotion, through tilting the head up towards the child, for example.

- While reading, so while the robot can detect someone speaking through the microphone. We have coded this to have a motivational emotion, through slow nods and opening the angle of the ears.

- A pause in reading, so when the robot is unable to detect someone reading for a fixed amount of time (for example, 10 seconds). We have coded this to have a questioning emotion, such as with a tilting head position.

- Session finish, which is when the teacher says that the reading session is over. This could be a fixed time (for example, after exactly 10 minutes) or a different action which the robot could sense. We have coded this to have a celebrating emotion, such as moving in a circle.

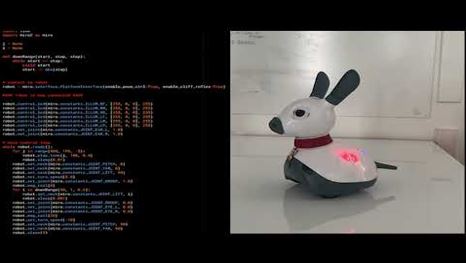

- Early finish, which is when the student decides to stop their reading session before the finishing time. We are still thinking about how the robot could sense this: either if no sound has been heard for over a minute, for example, or if the student does a specific action, such as clapping three times. We have coded this to have a sad emotion, with the robot looking down and the tail not wagging any more. Here is the example code of this:

Social Robots as Reading Buddies sample code

Throughout all these stages, we have also made use of the lights on the robots to portray what stage the students are on. This will allow the teachers to see the same.

We have learnt a lot in the project so far. For example, through the opportunity to talk with the younger students, we practised gathering data interactively, and how we can use this information. We also learnt a lot of new skills through our research, such as how we can receive papers from the writers and how we can use these effectively. Finally, we have experimented lots through coding by finding out how we can use the new functions in the miro2 library, as well as how we could use different libraries to overcome challenges such as not having a function to sense consistent sound, such as someone reading.

Our next steps

Our next steps for next year and beyond are to successfully complete the coding of this project and run a test with students in the Junior School, before finalising the code to make the robot reading buddy as effective as it can be. There are still a lot of problems that we need to solve for us to code the program successfully.

A key problem that we are facing now is that our robot currently cannot distinguish between a human voice (which can be constant) and a machine whirring away in the background. This is because the robot can only “hear” the difference between fluctuating noises and constant noises. There are many factors that contribute to this problem that we still need to test. Is it because the microphone is not good enough? Is it simply that the communication between the laptop, robot and lights is too slow for the robot to reflect what it is hearing? And how could we adapt our code to work with this?

It is problems like these which slow down the coding process. For example, there were times where the program would not send to the robot, which we struggled to fix for weeks. Or smaller problems, such as when I thought the program was not running but it was simply that the movements on the simulator that I had coded were not big enough for me to notice the impact of my code.

When all our coding works for each of the 5 stages, we are going to link this all into one bigger program, which will decide which stage the reader is at. For example, if no reading has been detected for x seconds, then the robot may go into the “pause” phase. We will need to experiment to see what timings suit these decisions best. While we continue to develop the coding, we will also need to constantly test and receive more feedback to improve. For example, how could we find the balance between distractions and interactions?

As you can tell, we have made progress, but we also have lots to do. We will continue to try to find effective solutions to the problems that we may encounter.

Reflection

We have all thoroughly enjoyed this project, and we also think that it has, and will continue to, help us build up several skills. For example, we have learnt to collaborate well as a team, being able to work both independently and with others. However, as previously mentioned we have encountered many challenges, and in these cases perseverance is key. Finally, we appreciate the project because it has been really rewarding and lots of fun to work with the robot and see our progress visually.

However, we cannot

do this project alone. As mentioned, we know it is vital that we receive

feedback and act on it. This is why we would also really appreciate any

feedback or suggestions that you may have for us! Feel free to complete this

form with any comments: https://forms.office.com/r/3yNJZEHBfy. Thank you so

much!

[1] Our video entry for Night of Ideas 2020: https://youtu.be/RlbzqTKAOTc

[2] Details about using Miro-E robots to combat loneliness for the elderly: https://www.miro-e.com/blog/2020/4/14/the-isolation-pandemic

Whilst the word ‘power’ has for a long time been associated with muscular strength, the word ‘knowledge’ has always been connected with the mind. The two words do not seem to have any connection whatsoever. However, today the world power has undergone a tremendous transformation. Today it is commonly recognised that the pen is mightier than the sword.

Whilst the word ‘power’ has for a long time been associated with muscular strength, the word ‘knowledge’ has always been connected with the mind. The two words do not seem to have any connection whatsoever. However, today the world power has undergone a tremendous transformation. Today it is commonly recognised that the pen is mightier than the sword. I remember receiving my first library card: the power granted – the exhilaration as the red light of the checkout scanner christened the book – my book. It is great that we have a student library as I, like many others, think libraries are essential. One reason is because they offer educational resources to everyone. Anyone can use libraries to succeed and have the answers to curious minds. Secondly, they preserve history and truth and the preservation of truth is important, now more than ever. Libraries, which house centuries of learning, information and history are important while we fight against fake news.

I remember receiving my first library card: the power granted – the exhilaration as the red light of the checkout scanner christened the book – my book. It is great that we have a student library as I, like many others, think libraries are essential. One reason is because they offer educational resources to everyone. Anyone can use libraries to succeed and have the answers to curious minds. Secondly, they preserve history and truth and the preservation of truth is important, now more than ever. Libraries, which house centuries of learning, information and history are important while we fight against fake news.