Classics teacher Callista McLaughlin examines the deeply enriching influence that a school production of a drama from Classical literature has had on learning in Years 10 and 12.

A major focus of my teaching of the Classics this year has been the Tragedy genre, in the Greek Theatre paper in A-Level Classical Civilisation, and the Verse Literature component of Greek GCSE. The Year 10 production of Euripides’ Women of Troy invigorated this task in more ways than one.

Women of Troy is set in the aftermath of the capture of Troy by the Greeks, which ended the conflict that is depicted most famously in Homer’s Iliad. As one Year 10 remarked when Hattie Franklin and I were team-teaching an A-Level taster on Homer’s epic, ‘Euripidesdramatises the fate the women fear in the Iliad’. Our eyes were widening at breadth of knowledge of Classical literature suggested by this observation, when we remembered that this pupil was in the play. This was the first of many gifts from this production to reach our Classics classrooms.

Beyond the classroom

While its dramatic content comes, like much of Tragedy, from myth, Euripides wrote and produced this play during the Peloponnesian War of the 5th Century, and it has been considered his response to its horrors.[1] His ever-empathetic, strikingly universal expressions have apparently enabled others to satisfy the same longing. Thus, millennia later, the play was notably produced with an astonishingly pacifistic slant, in Berlin in 1916.[2] In fact, the text has been re-translated and re-produced over time with constant urgency, in response to various world events, including the Boer war, European imperialism in Asia, the September 11 attacks and the US invasion of Iraq.[3] This term our school production of the tragedy was shot through with meaning and impact by the war in Ukraine.

The pain expressed by the chorus of women on the destruction of their homeland, and their questions for the future– where might they live? who might forcibly take them as a wife or lover? what might become of their children? – echoed the anxieties we see expressed by Ukrainian refugees on the news all too closely. Deb McDowell’s choice to set the production in a modern-day refugee camp meant it looked like what we see on television too: in class Year 12 remarked on the poignancy of each chorus member bearing baggage. The blue and yellow flag draped over the tiny casket of a slaughtered innocent towards the end of the play wove together the connections it was impossible to avoid throughout, as an audience member.

Inside the classroom

The unanimous observation of the Year 12 Classical Civilisation students who watched the production, and the Year 10 Greek students who were in it, was that these allusions increased their empathy with and understanding of Euripides’ characters. Moreover, just as powerfully as the modern setting brought the ancient tragedy to life, the tragic dialogues in turn brought the modern setting to life, with the potential to inform our understanding of the current state of war.

The play yielded high-level discussion from the Year 12 audience, from exploring their set author Euripides more deeply to making inspired proposals for setting their set plays in 2022. For the Year 10 actors, it was invaluable immersion. They have produced articulate, thoughtful responses to what they learned from the process, but also shown me what they learned, through the heightened emotion and energy with which they have tackled the – often tough and trying –[4] task of translating their set text.

The fantastic production set me up for an increased engagement with its content – though their spontaneously wailing like a tragic chorus when a character disrespected a Greek god surpassed my expectations! Less anticipated, and truly exciting, is the effect it has had on their handling of what is challenging Greek, particularly for students who have been learning the language for less than a year. Seeing a play, rather than a mere puzzle of particles and irregular verbs, they have begun to use their instinct and intuition to make logical connections between the different lines of dialogue. I am also taking advantage of the now-revealed acting skills of the class. The activity of performing a dialogue, proven effective for studying plays in translation,[5] has in some ways even more exciting potential when tackling the original Greek.

Conclusions on co-curricular cultivation

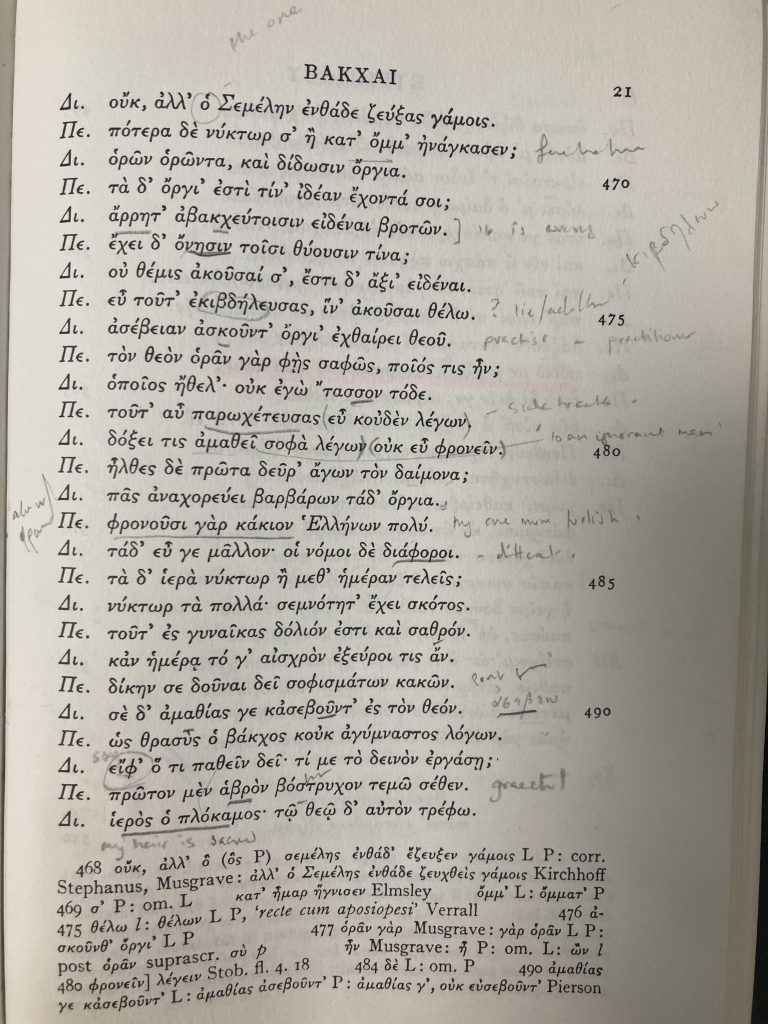

With the theatre

coming back into our lives, the Classics pupils will have seen two external

productions this year (the Bacchae in January and an Oedipus /

Antigone mash-up later this month). Such trips and exposure are inspiring,

especially when trying to bring such ancient texts back to life, but co-curricular

immersion, right here at school, magnifies this potential marvellously. And for

the non-Classicists starring in the tragedy, it has been a brilliant

intellectual and creative challenge, which will have allowed them to grow as

students, whatever their field of interest.

[1] Croally, Neil (2007). Euripidean Polemic: The Trojan Women and the Function of Tragedy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-04112-0

[2] Sharp, IE (2018) “A Peace Play in Wartime Germany? Pacifism in Franz Werfel’s The Trojan Women, Berlin 1916.” Classical Receptions Journal, 10 (4). pp. 476-495. ISSN 1759-5134 (https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/129895/).

[3]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Trojan_Women#Modern_treatments_and_adaptations

[4] Hunt, S. (2016), Starting to Teach Latin. London: Bloomsbury p.126.

[5] Speers, C. (2020). “How can teachers effectively use student dialogue to drive engagement with ancient drama? An analysis of a Year 12 Classical Civilisation class studying Aristophanes’ Frogs.” Journal of Classics Teaching, 21(41), 19-32. doi:10.1017/S2058631020000112