Children’s learning about relationships, personal agency and emotional wellbeing is the responsibility of the whole community from infancy onwards, writes the Head of Junior School, Claire Boyd

It has been eighteen months since the Department of Education made the teaching of RSHE (relationships, sex and health education) statutory in all primary schools. Informed by a recognition that “today’s children and young people are growing up in an increasingly complex world and living their lives seamlessly on and offline”[1], it is now expected that, by the end of Year 6, children will be able to recognise diversity of family set-ups, appreciate the tenets of caring, respectful relationships and understand how to navigate life online safely.

Following closely behind these changes to RSHE, Ofsted also published its Review of Sexual Abuse in Schools and Colleges in June last year. A sobering read, the report found not only significant failings in the robustness of safeguarding frameworks in many schools, but also suggested that the teaching of Personal, Social & Health education frequently fell short of its intended purpose. The findings for girls were particularly concerning, with high numbers stating that they “do not want to talk about sexual abuse…even where their school encourages them to”, due to a fear of not being believed or being ostracised by their peers. Others worry about how adults will react and feel concerned that they will lose control of the situation in which they find themselves. Although most of the testimonies collected by the review focused on children of secondary age, children aged 11 and under were referenced as victims of sexual abuse and harassment in schools, often describing similar preoccupations as older girls about the implications of speaking up about their experiences.

Rising to the challenges

With these changes and recommendations from the DfE and Ofsted fresh in our minds, in the Junior School we have begun to evaluate the impact and efficacy of our approach to helping students navigate relationships. We are attempting to measure our success against broad and subjective statements, including whether a child is able “to recognise who to trust and who not to trust”, can “judge when a friendship is making them feel unhappy or uncomfortable”, and can “manage conflict [and] seek help or advice from others, if needed”[2].

Whilst there can be no doubt that high quality, systematic teaching of RSHE is imperative for twenty-first century schools, at WHS our reflections have led us to believe that real progress relies on much more than the rewriting of curricula and the upskilling of teachers on their safeguarding responsibilities. Certainly, a nuanced, proactive approach – evident, for example, in the innovative Wimbledon Charter (the WHS-led response to Everyone’s Invited) – is urgently needed, and ultimately, sustainable and far-reaching change must start with the earliest childhood experiences.

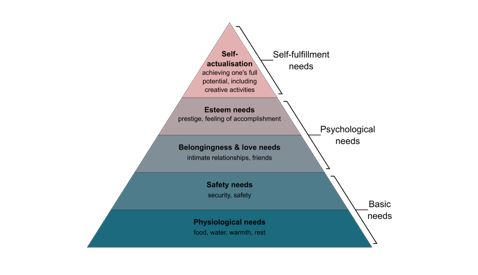

A wholesale and deliberate realignment of how we – teachers, parents, families and communities – nurture our children from the Early Years onwards is essential. If the gold standard we want our young people to attain is self-knowledge that can be communicated with confidence and agency, then we must ensure we embed these skills in their everyday contexts from infancy. We must ensure that we place the principles of character development, emotional resilience and autonomous decision-making in the foreground of everything our children experience both at home and at school. This requires parents and teachers to fight the inevitable urge to smooth over and fix difficult situations for the children in our care. It means we must resist speaking on behalf of our young people, and must consciously fight against the gender biases related to the stereotypical behaviours of ‘troublesome boys and compliant girls’.

Schools as leaders and allies

Our ambition to release future generations from power imbalances such as those reported on by Ofsted depends on schools leading the way. Schools must support parents and families to engage, wholeheartedly, in giving agency to our girls to become comfortable with quiet assertiveness from a young age. We must prioritise opportunities to develop the skills which allow them to resolve conflict for themselves, even if this runs the risk of them experiencing some discomfort along the way. If our young children have not developed the voice to say no, to set their own boundaries and resolve the conflicts they have experienced during early childhood, how can we expect them to do so as teenagers and adults?

What our young people – and our

girls in particular – require from us is the bravery to lead a step change; one

that sees teachers and parents walking alongside them, coaching and empowering

them to develop the resilience and character to be happy, successful and

productive members of society.

[1] N.Zahawi, Department of Education, 2021, Statutory Guidance by the Secretary of State, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education/foreword-by-the-secretary-of-state

[2] Department for Education, Relationships, Sex & Health Education (RSE), Statutory guidance for governing bodies, proprietors, head teachers, principals, senior leadership teams, teachers, 2019, p20 –p22, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1019542/Relationships_Education__Relationships_and_Sex_Education__RSE__and_Health_Education.pdf

We prefer ‘Stepping In’…… I fondly call my new cohort of Year 7s on their first day (or should I say term?), ‘turtles’…. their backpack has their life in it and appears to dwarf them as they wide-eyed, set off down school corridors navigating their way around what will be ‘home’ for the next 7 years.

We prefer ‘Stepping In’…… I fondly call my new cohort of Year 7s on their first day (or should I say term?), ‘turtles’…. their backpack has their life in it and appears to dwarf them as they wide-eyed, set off down school corridors navigating their way around what will be ‘home’ for the next 7 years. The crux of her book ‘Daring Greatly’

The crux of her book ‘Daring Greatly’