She considers the ‘illusion of mastery’ and how metacognition can help students avoid falling into this trap with our games players

In Make it Stick, P. Brown, H. Roediger III and M. McDaniel discuss the Science of Successful Learning. In general, it’s an incredibly interesting book peppered with examples of how we learn most effectively. Being aware of how we learn and think, can result in an improved ability to problem solve, decision make and over-come hurdles (apologies for the sport pun!). The content is enjoyable, supported by various examples and easy to consume – it’s almost as if they know how to convey information and make it memorable!

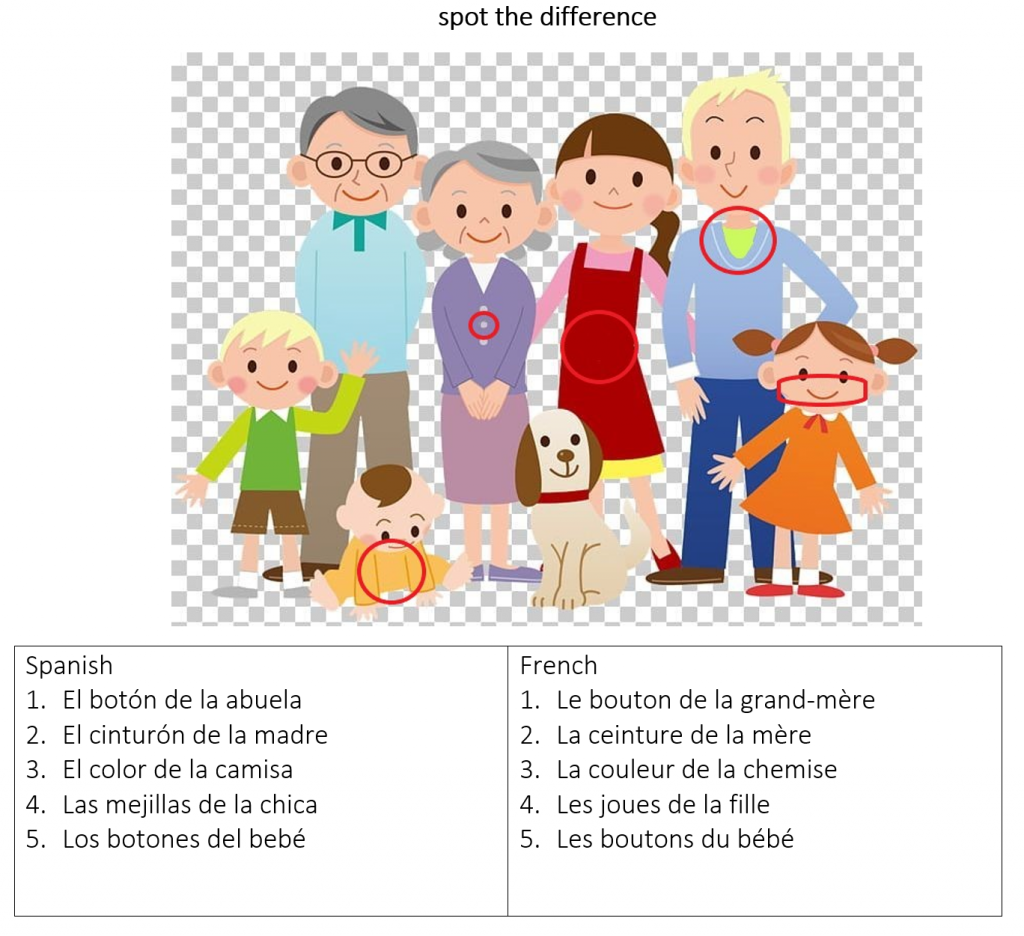

This book begins by addressing how learners can fall into the trap of the ‘illusion of mastery’. This is where pupils think they have grasped what they have been taught but once tested fall short. Frequently the revision strategy for this approach would involve making notes and then reading and re-reading them time and time again, simply creating the feeling and appearance of mastery.

With the return of competitive sport on the horizon, I turned my thoughts to how I was going to avoid this illusion with our Wimbledonian games players and make the most of this insight.

Practically in Sport, we must then be careful of striking the balance between enhancing the efficiency and fluency of skills, at the detriment of pupils being able respond flexibly and adapt to an unknown scenario during competition.

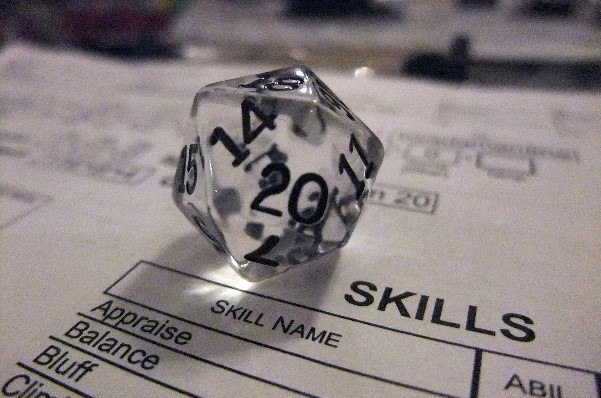

When teaching open skills, for example during invasion games eg Netball, adopting a games-sense approach is a desirable method. This allows pupils to become more self-aware, encouraging meta-cognition and evaluation of their own success criteria. It helps them to really judge when they have grasped a skill and perform it under pressure, rather than think that they have without success to prove it. This means that the pupils are improving their skills in a more realistic environment so that they are transferable to high-level competition against other schools. Furthermore, the ability to reflect on your performance and then have a flexible skill set when responding is useful when a taught ‘set play’ is challenged by the opposition. This means that pupils can’t fall into the illusion trap as they are constantly being challenged and having to apply their knowledge and skills appropriately.

Another important aspect of learning in sport is the ability to recognise when similar situations occur during this open environment. In a match context, quick recognition of when a ‘set play’ could be implemented is beneficial as it allows pupils to respond effectively whilst under pressure. It also encourages reflection on your own learning and performance.

Although this games-sense approach needs a good skill base to be effective, I think that it prepares pupils for competitions more effectively by helping them to become better critiques of their own learning than solely focusing on closed drills.