Spring Focus: Metacognition – students driving their own learning through reflection

Teaching and learning Gem #28 – exam/assessment wrapper

Lots of us are promoting metacognition in the self-reflective reviews we are setting for students following the Spring Assessments. By reflecting on their own performance, we are encouraging students to think about their skills/understanding and become self-regulated learners.

I’m aware that for self-reflection to work, students need to take it seriously, realise its impact rather than pay lip-service to it. We can help them do this in the way we approach this sort of task. Additionally, the first minute of this video is great at helping students realise that self-reflection is an important part of life for all sorts of people: it’s not just something that happens in the classroom.

Right now, there is lots of great practice going on around the school, so I thought I’d share five different approaches from five departments to give a flavour:

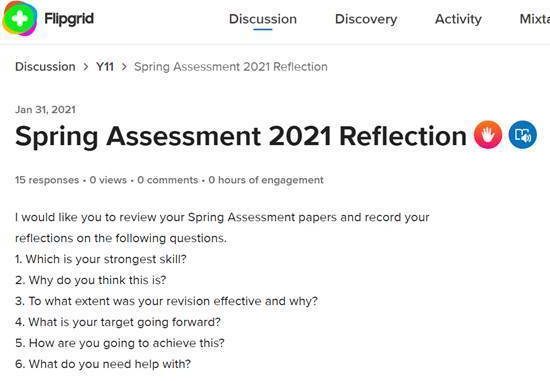

- Flipgrid for powerful, verbal self-reflection (Claire Baty)

Claire used Flipgrid as a way for students to send her a video of their self-reflection. This was quick to set up and powerful in its impact. Using a moderated Flpgrid board meant that students couldn’t see each other’s video reflections, so it felt like a personal one-to-one discussion with their teacher. Claire could then easily video a response back to the student using the platform. Claire says, “I am convinced that verbalising their self-reflection helps students to clarify their ideas and take on board their own advice more readily. I think they give more thought to something they have to say out loud than they would if I’d just asked them to jot down their ideas on OneNote.” Here were her instructions posted on Flipgrid.

NB: on a technical note, if you set up a moderated board and then want students to rewatch their video submission and see any video feedback from the teacher, they need to go to my.flipgrid.com Watch out for a video about this from Claire.

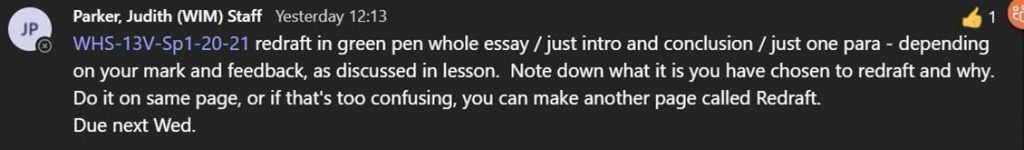

- Redrafting with students noting why they are redrafting (Judith Parker)

Giving students the time to redraft is an invaluable metacognitive process. This is a slow/deep activity and cannot be rattled off quickly – it’s worth the lesson or homework time in gold. Judith asked students to engage with their assessment responses and think carefully about how to improve their own work. She increased the metacognitive challenge by asking student to note down why they have chosen to redraft a particular section. Making their thought processes clear to themselves helps them drive their own learning.

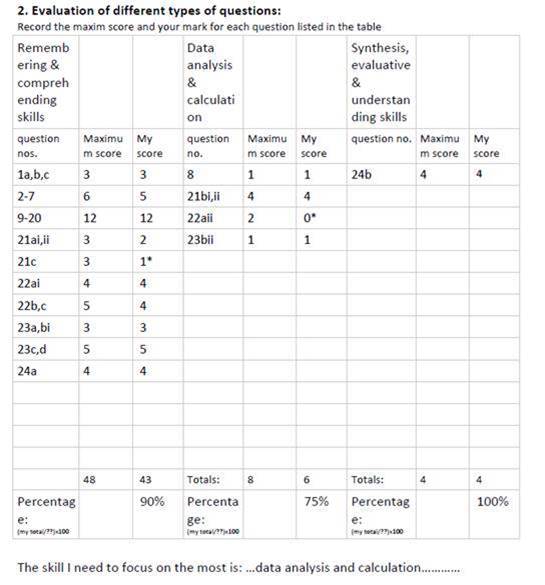

- Students categorising the questions into skill type and reviewing their performance in these different skills (Clare Roper)

This is one part of a self-reflection worksheet that students complete on OneNote. By identifying and categorising the skills in each question, Clare is asking students to think in a structured way about strengths and to identify for themselves next steps in their learning. Spotting patterns in their performance makes clear to students how to approach further learning, and helps them see the sorts of skills they need to employ in future assessments/tests.

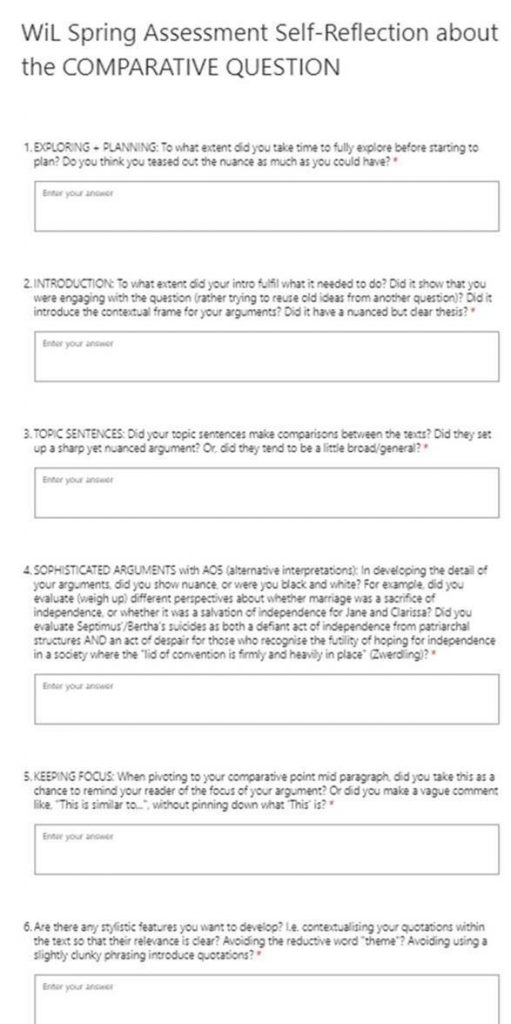

- Microsoft Forms for targeted reflection on specific skills/questions (Suzy Pett)

A questionnaire of focussed, self-reflection questions can be created using Microsoft Forms. Of course, these questions could easily be completed by students in OneNote, too.

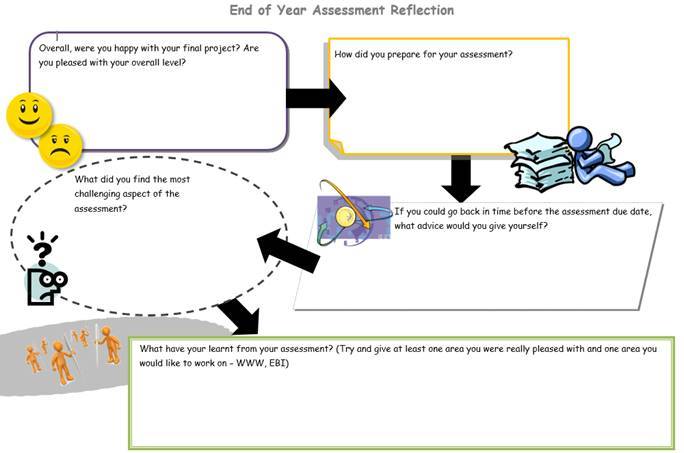

- And here is another example of a self-review for students at KS3 (Steph Harel)

I really like this metacognitive question on the below worksheet, “If you could go back in time before the assessment due date, what advice would you give yourself.” Encouraging a ‘self-dialogue’ is really valuable: the more students can ‘talk’ to themselves about what they are doing, the better.