WHS Head of French and Mandarin, Claire Baty, extols the crucial, intrinsic importance for linguists of broadening their cultural and imaginative horizons, and discusses two school initiatives to support this – Linguistica magazine and its associated club, Linguistica and Friends

My MFL colleagues and I are currently busy proof-reading articles for the summer edition of the department’s Linguistica magazine. Each term, as the deadline for submissions comes and goes, I feel a sense of curiosity tinged with apprehension. I am excited to read the fruits of students’ efforts beyond the language classroom but I can’t escape the underlying worry that they may not feel sufficiently impassioned to actually submit articles for publication. Why is that?

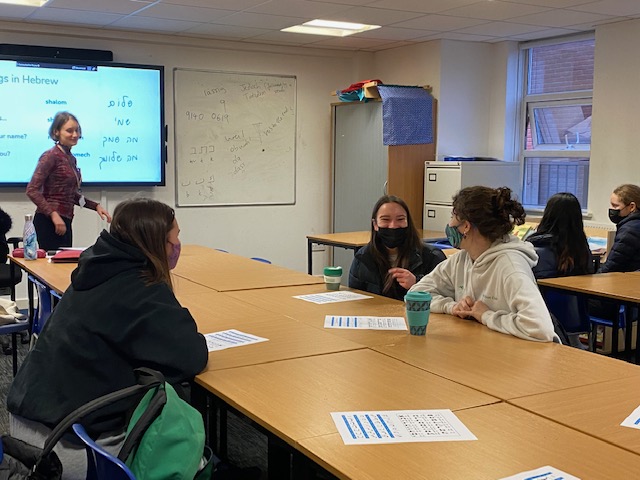

Linguistica was created to be more than just a magazine – it is a space to explore language learning and the myriad opportunities this affords. Fortunately, post-covid, our classrooms have once again become inspiring, collaborative spaces where students can assimilate new language through role plays, and can put their heads together, literally, to work out the rules of a new grammatical structure. Whilst rote learning of vocabulary and grammar rules is important, language learning is and should be much more than this. An understanding of the music, film, fashion, food, history, politics, literature, geography of the country is just as significant as being able to use the words correctly.

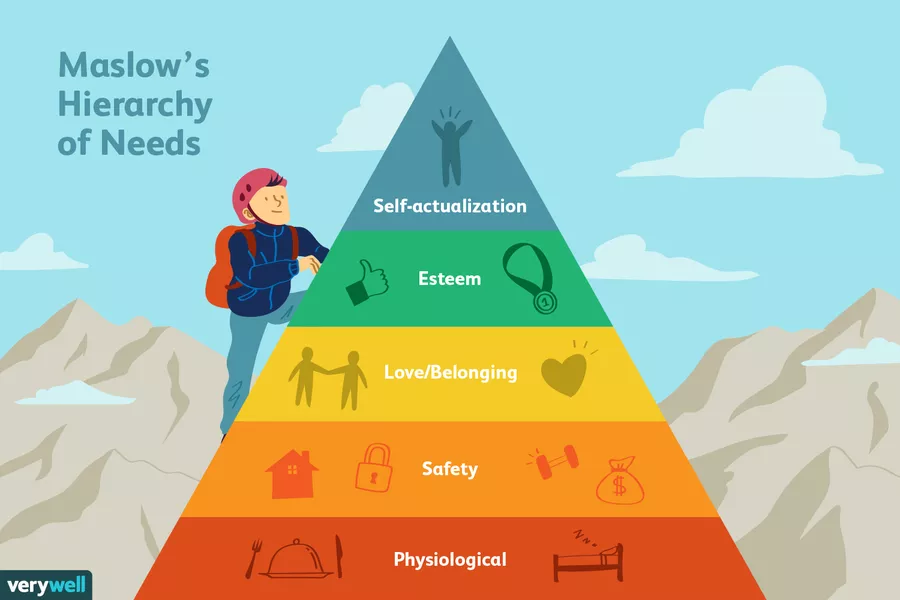

It is this cultural understanding, coupled with strong syntactical awareness, that ultimately creates an expert communicator. In a world that is increasingly driven by technology, it is our ability as human beings to empathise and communicate with each other that will become the most important 21st century skill. Linguistica is a platform for our students to engage with the cultural, social and political world of the country they are studying.

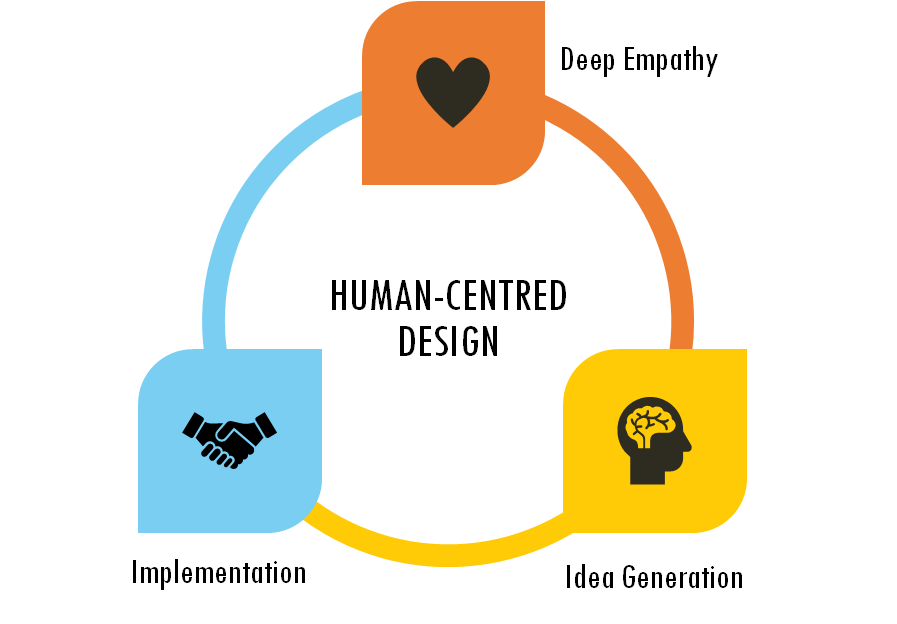

This term our ‘Linguistica and Friends’ club has whole-heartedly embraced the STEAM+ ethos by inviting other departments to deliver workshops, seminars and lectures exploring the interplay between their subject and MFL. Our aim, to enrich our students’ understanding of the world around them. We have encouraged them to ask big questions which force them to make connections between their subjects such as:

- How does Maths help me with translation in a foreign language?

- Does learning Latin mean I am better at French?

- If we all spoke the same language would there be less conflict in the world?

- What helps me understand people better – learning their language or learning their history?

- Science has nothing to do with languages: discuss.

- Is computer code a language?

We have enticed them to see things through a different lens. Ultimately no discipline can exist in isolation and learning a language really does entail learning a whole other perspective on the world.

Why does this matter?

The WHS Civil Discourse programme has as its core aim for our students “to be truly flexible, robust and open in their thinking, and for the world to re-awaken itself to the notion of real debate and discussion, based on authentic encounters between enquiring hearts and minds”. Exploring topics we thought we understood from a new perspective allows for nuanced thinking and offers access to opinions which differ from our own.

We all start out with a ‘blik’ or worldview, informed by our upbringing, circumstances and personal experiences. Our ‘blik’ tells us how to interpret the world, and we then choose to embrace the facts that support our ‘blik’ whilst selectively ignoring or explaining away those that go against it (R.M Hare in his response to Anthony Flew’s 1971 Symposium). Our job as teachers is to challenge a student’s ‘blik’ by offering them diverse ways to engage with subject material outside of the classroom. To stride out into the world, our students need to be able to see that world and how concepts connect with in it. This was exactly the aim of ‘Linguistica and Friends’ this term when we offered sessions designed to show the connections between subjects that the students in KS3 at least, often see as disparate.

But why do I worry our students won’t engage? Why am I concerned they won’t be as excited as I am about the opportunity to spend my lunchtime time considering the flaws of a translation of the New Testament? As teachers we can see the value of inter-connected thinking, we are excited by this opportunity to engage with the big picture, and we are frustrated by how exam specifications can thwart and potentially diminish a student’s desire to explore. For the students, however, “c’est l’arbre qui cache la forêt” and the demands of exams can hinder true scholarship, taking away the passion, the willingness to engage and explore just for the fun of it.

And this is precisely why Linguistica matters. It is in this co-curricular space that we can open our students’ minds to new concepts, encourage them to challenge their pre-existing ideas without the judgement of an exam. Here they can discover their passions, find out who they are and what inspires them.

So look out for this term’s edition of Linguistica, which will be published in hard copy before the summer holidays. It will showcase the creative and eloquent writing of our fantastic MFL students, who have had success in all manner of competitions. You can find out more about how our students engaged with the inspiring ‘Linguistica and Friends’ workshops, as well as the big questions considered by Years 8 and 9. Here is a flavour of what they explored.

- The interplay between Maths and language exemplified by the deciphering work done at Bletchley Park during WW2

- How textiles and fashion are inextricably linked to culture and history, as demonstrated by traditional Chinese Hanfu

- The use of Greek in the New Testament: symbolism and translation. How the meaning of a text is not separate from the language in which it is written.

- Furthering our understanding of scientific concepts by exploring the derivation of scientific words and their language of origin.

- The role of cognates, body language and demonstration when making sense of a language you don’t speak. (Loom weaving in Italian.)

- How Semitic languages fit into the European languages we commonly learn in school.

- How the use of language in popular film could be used as a way of raising awareness of languages at risk of dying out. With a focus on Polynesian languages and the Disney film Moana.

- The recent presidential elections in France and how language can be used to persuade, convince and influence.