Mrs Efua Aremo, a Design & Technology Teacher at WHS, explores whether a ‘human-centred design’ approach can help us deliver solutions which are effective in meeting local and global needs.

A World full of Need

It is impossible to adequately describe the profound losses experienced over the past 12 months. There are the more measurable losses such as employment, finance and health but then there are also the relational losses caused by isolation and tragic bereavements. It has been a brutal year for many, and the impact of the pandemic has been acutely felt by the most vulnerable.

When we are confronted with such needs both locally and internationally, we desire to help in any way we can, as Mr Keith Cawsey observed in his December article. However, it doesn’t take long to discover that people have many different types of needs and there are many different types of help we might provide.

What do we need?

“I need blue skies, I need them old times, I need something good…”

Those words from singer-songwriter, Maverick Sabre, powerfully captures the sense of longing many of us feel for simple things like sunshine and for more intangible things we struggle to name.

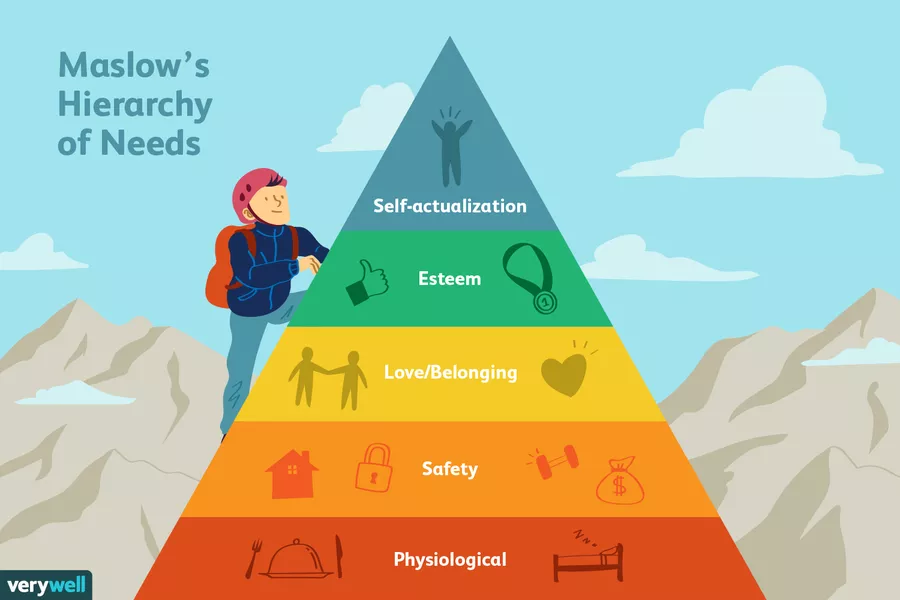

One of the most popular ways of categorising human needs was introduced by Abraham Maslow in 1943, it is known as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Maslow’s hierarchy describes five different levels of need:

- Physiological: basic needs such as water, food and sleep.

- Safety: security and freedom from danger.

- Love/Belonging: the desire for relationships of love, affection and belonging.

- Esteem: a stable, positive self-evaluation and respect from others.

- Self-actualisation: the desire to realise one’s full potential.

How can we help?

“Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.”

The old proverb quoted above helps us as we think about the types of help we might provide to people in need.

Through observing the charitable work of religious and humanitarian organisations, we can identify at least four levels of assistance:

- Emergency Relief: giving direct help to meet immediate needs – “give a man a fish.”

- Longer-Term Development: giving assistance which results in a person or community being able to meet their own needs – “teach a man to fish.”

- Social Reform: overcoming the adverse social conditions or systems which lead to injustice or oppression.

- Advocacy/Campaigns: providing information about needs to people who are able to help.

This article focusses on the first two categories.

When Helping isn’t Helpful

Sometimes, efforts to provide help do not achieve the intended result. For example, in 2010, a US aid agency installed 600 hand pumps to supply clean water for rural households in northern Mozambique. The aim was to help the women and girls who travelled long distances to collect contaminated water from wells and rivers. The aid agency imagined that the pumps would save time, improve health conditions and empower the women to start small businesses. However, these water pumps were not used by most of the people in the community. What went wrong?

Helping those who are different to ourselves

Though the desire to help others is always to be commended, it can often be accompanied by wrong assumptions which hinder our ability to help effectively. This is especially true when we are seeking to help people from a different economic status, ethnicity or culture to our own.

It is tempting to assume we know what people need, especially if they have basic physiological needs which are not being met. However, even in his original paper, Maslow acknowledged that human beings are more complex than the tidy logic of his hierarchy suggests. He recognised that the lower-order needs do not need to be completely satisfied before the higher-order needs become important. Therefore, when helping the neediest people in society, we need to get to know them beyond their basic needs.

Recognising this fact is key to understanding what went wrong with the water pumps in Mozambique. The aid agency seems to have stereotyped the rural women as passive, needy people and so failed to ask their opinion about where best to locate the new pumps. They focussed their attention on providing access to clean water but did not account for the fact that the original water sites were “important social spaces where women exchanged information, shared work, socialized their children, and had freedom outside the home.” The new sites lacked the privacy, shade and areas for laundry and bathing which the women valued, and so the new water pumps were rejected.

Thankfully, we can learn from experiences like this to devise better ways of helping people in need.

Human-Centred Design: A Better Way?

“In order to get to new solutions, you have to get to know different people, different scenarios, different places.”

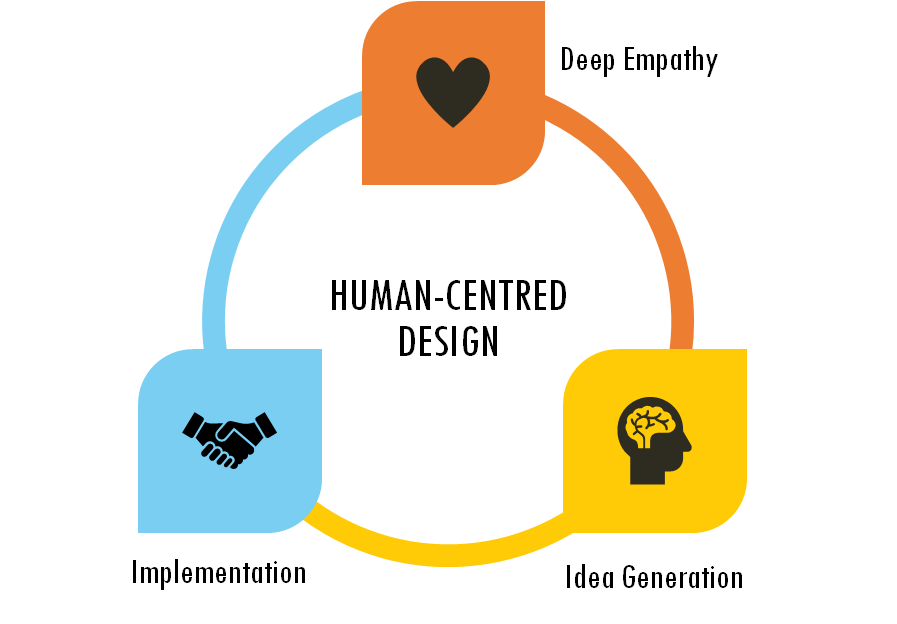

Human-centred design (also known as ‘design thinking’) is an approach to problem-solving which involves partnering with those in need of help to deliver the solutions which most benefit them. It involves “building deep empathy with the people you’re designing for… as you immerse yourself in their lives and come to deeply understand their needs.”

But this does not mean that those who are being helped are only consulted at the start of the process. Human-centred design is a non-linear collaborative process which involves back-and-forth communication between those helping and those needing help. Together they produce many design iterations until they find a solution which best suits those who need it. It is obvious how this approach might have led to better results in Mozambique.

Human-centred design involves looking beyond their needs and acknowledging the full humanity of the people who we wish to help: appreciating their culture, discovering what they value, and how they might contribute to meeting their own needs.

Taking a more human-centred approach enabled Jerry Sternin from Save the Children to successfully deal with the problem of severe malnutrition amongst children in rural Vietnam in the 1990s. Previous attempts had relied on aid workers providing resources from outside the affected communities – these methods proved unsustainable and ineffective.

Sternin discovered that despite their poverty, some mothers were managing to keep their children healthy. So he sought to learn from them and discovered what they were doing differently from their neighbours: they were feeding their children smaller meals multiple times a day rather than the conventional twice daily. They were also adding to these meals freely available shellfish and sweet potato greens even though other villagers did not deem these appropriate for children.

By empowering the mothers to train other families in these practices, Sternin was able to help the community help itself. Malnutrition in northern Vietnam was greatly reduced through implementing this effective, empowering and sustainable local solution.

The Wonderbag

Another sustainable design solution is the Wonderbag, which is a non-electric slow-cooker. Once a pot of food has been brought to the boil and placed in the foam-insulated Wonderbag, it will continue to cook (without the need for additional heat) for up to 12 hours. This product was developed in South Africa to address the problems caused by cooking indoors on open fires. It has vastly improved the lives of the women who use them because cooking with the Wonderbag uses less fuel and water, improves indoor air-quality, and frees up time which many girls and women have used to invest in their education, employment, or to start their own businesses. Local women use their sewing skills to customise the Wonderbags with their own cultural designs.

Human-Centred Design at WHS

In Year 9, design students at WHS are tasked with designing assistive devices for clients with disabilities. One of the first things they need to do is get to know their users; seeing beyond their disabilities and discovering who they are, what they love, and what they hate.

One pupil found that her client who suffers from benign tremors loves to paint but hates having to use massive assistive devices because they draw too much attention to her. This pupil is currently developing a discrete product which will help their client paint again, meeting her needs for esteem and self-actualisation.

Helping Others in this Time of Need

In the midst of a global pandemic and in its aftermath, we will encounter people in need of both emergency relief and longer-term development assistance. Perhaps by adopting a human-centred design approach, we will be able to help others in ways which are effective, sustainable, and which recognise the beautifully complex humanity of those in need.

- Rawpixel.com, Shutterstock Image ID: 212764069, n.d.

- Keith Cawsey, “What Has COVID Taught Us about Our Relationships with Others?,” WimTeach, 10 December 2020, http://whs-blogs.co.uk/teaching/covid-taught-us-relationships-others/.

- Maverick Sabre, I Need (Official Video), 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GZNtticFI60.

- Abraham H. Maslow, A Theory of Human Motivation, 1943, http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm.

- Joshua Seong, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, 2020, https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-4136760.

- Timothy Keller, Generous Justice (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2010); Oxfam GB, “How We Spend Your Money,” n.d., https://www.oxfam.org.uk/donate/how-we-spend-your-money/.

- Africacollection, Shutterstock Image ID: 714414436, n.d.

- Emily Van Houweling, Misunderstanding Women’s Empowerment (Posner Center, 2020), https://posnercenter.org/catalyst_entry/misunderstanding-womens-empowerment/.

- Emily Van Houweling, Misunderstanding Women’s Empowerment.

- Emi Kolawole, Stanford University d.school cited in IDEO.org, The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design: Design Kit, 2015, 22.

- IDEO.org, “What Is Human-Centred Design?,” Design Kit, n.d., https://www.designkit.org/human-centered-design.

- Monique Sternin, “The Vietnam Story: 25 Years Later,” Positive Deviance Collaborative, n.d., https://positivedeviance.org/case-studies-all/2018/4/16/the-vietnam-story-25-years-later.

- Jerry Sternin and Robert Choo, “The Power of Positive Deviancy,” Harvard Business Review, 1 January 2000, https://hbr.org/2000/01/the-power-of-positive-deviancy.

- Conasi.eu, Wonderbag CC BY-NC 3.0, n.d., https://www.conasi.eu/cocina-lenta/3088-wonderbag-mediana-batik-rosa.html.