Written by: Maria Pavin

This essay makes generalisations and assumptions that may not be true to all people and is modelled off what is seen in the wider world, particularly in western cultures.

The book ‘The beauty of everyday things’ by philosopher and Japanese folk craft pioneer Soetsu Yangai is a collection of essays discussing the relationships people have with objects. His main focus is on folk craft, ‘mingei’ in Japanese, and how the appreciation for these objects has diminished through time.

Folk craft objects are the objects of the everyday, not created by renowned artists and are neither expensive nor rare. Through his book, Yangai shares the importance of them and their natural beauty.

Although I disagree with his idea that objects have moved away from serving a truly utilitarian purpose and instead have become focussed on the aesthetics, with his idea that we no longer appreciate the objects used day to day is that one that resonates most powerfully. The epidemic of single use objects highlights this, whilst the recent ban on some of the most polluting single use plastics has made a step to reduce our reliance on them, the underlying problem of overconsumption still prevails.

So how does beauty relate to our consumption of products and our appreciation of them? One of the ideas that has settled in our minds mostly unconsciously is that beauty is something remarkable, unattainable or something that can only be attributed to the most significant things. Is it perhaps that if we label too many things ‘beautiful’ then suddenly the value of the word diminishes and society, which has been built to hold up those beautiful unattainable things, will crumble? Of course, in actuality societal collapse will not occur after coming to the realisation that beauty can indeed be found in almost anything, but it may help us to value the things we have more. Yangai explores this by saying ‘Beauty and life are treated as separate realms of being. Beauty is no longer viewed as an indispensable part of our everyday lives’ but in Yangai’s opinion, we will find the most beauty in that of the everyday. As he references that the very first people to recognize this beauty in ‘miscellaneous objects’ was that of the ‘first generation of tea masters’ and the ‘ido tea bowls’. These bowls now reaching the status of ‘omeibutsu’ (object of great renown) and thus high value is a testament to the way they were crafted.

However, beauty cannot and should not be found in every object that exists, even if there is always an element of beauty in most;to label an object as ‘beautiful’ must be conserved for those which wholly embody it. So which objects are beautiful? Yangai tells us that through the lens of folk craft, objects that are beautiful are those that which ‘honestly fulfil the practical purpose for which they were made.’ nYangai suggests the way to achieve a ‘kingdom of beauty’ is to ‘not place emphasis on appearance to the detriment of utility’. This is important to consider especially on the theme of sustainability and consumption, as the removal of the unnecessary can greatly reduce the materials and waste produced by an object.

Yangai writes: ‘what matters is not whether the manufacturing is new or old but whether the work is honest and sincere.’ However, as Yangai wrote this before the age of AI and automation the question of whether machines can be ‘honest and sincere’ arises. Although the company which programmes the machines and manufactures the products may have ‘honest and sincere’ intentions, many of the principles set out by Yangai require a sense of consciousness of the thing producing the object.

This contradicts some of his further statements that ‘no machine, no matter how powerful, can match its (the human hand’s) freedom of movement’ ‘modern-day organization, machinery, and labour conditions are not suited to the honest and sincere production of utilitarian ware’ therefore implying that his earlier statement does not encompass all new manufacturing but instead the resurgence of the production of folk craft and how this can be applied to a modern world.

In ‘Ways of seeing’ by art critic and essayist John Beger chapter one he states ‘we never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves.’ Applying this to the trend cycles that has exponentially sped up as a result of overconsumption and capitalism we can see how in context all objects can be deemed as valuable and thus beautiful. Yangai highlights this in his essays stating that ‘though these objects [folk craft] are the most familiar to us throughout our lives, their existence has been ignored in the flow of tie, because they are considered low and common’

On the contrary objects surrounded by those that we view as ugly or cheap (not in the monetary sense) can therefore become of little value themselves. Social media perpetuates ideas of grandeur and beauty, most to be unattainable whether that be to cost, scarcity or simply that it is falsified. Yet even when knowing this we apply them to our everyday lives. Suddenly what once was beautiful is bland and what was once a rarity is banal.

But could one see too much beauty in things, consumerism has led to people buying endless amounts of things they do not need, weather it is because they have been tricked into thinking they do or if they simply ‘want’ to have the item. Is it that they deem the objects as ‘beautiful’ or is it from other desires such as those to collect and surround themselves with objects of value. Reselling offers an interesting outlook on the value of objects, the main cause of reselling is the idea of exclusivity. If these products were not exclusive, then they would largely not be resold furthermore people’s desires for rare and unobtainable objects drive this market creating platforms where products are sold for tens or hundreds of pounds more than they are worth. By applying Yangai’s principles of folk craft, the mere idea of reselling contradicts that of the beauty of everyday things. Regardless of the fact that resold products are not those of folk craft and the every day, I think it adds an interesting perspective of why people find value in exclusivity especially when it comes about through processes as monotonous as mass production.

Furthermore, by applying John Berger’s description of how people perceive things in that ‘although every image embodies a way of seeing, our perception or appreciation of an image depends also upon our own way of seeing’, every object becomes exclusive for no two people can perceive it in the same way, therefore the correlation of scarcity to value loses some of its influence.

John Berger in chapter five of ‘Ways of seeing’ describes how ‘A patron cannot be surrounded by music or poems in the same way as he is surrounded by his pictures…. The[y] show him sights: sights of what he may possess. This perhaps gives an insight into why we feel the need to buy so many things, with so much diversity in culture, arts and academics surrounding ourselves with things that remind ourselves of them it helps to create our own identity as surround ourselves with things that may otherwise be unobtainable. After all, how do you represent the pursuit for knowledge on a wall, if not for a bookshelf? John Berger goes on to reference the anthropologist Levi-Strauss who wrote ’It is this avid and ambitious desire to take possession of the object for the benefit of the owner or even of the spectator which seems to me to constitute one of the outstandingly original features of the art of Western civilization.’ This reflection on the history and nature of the human condition to feel the need to possess something for ones own gain can perhaps give an explanation for overconsumption. Perhaps we have always felt the need to acquire products and objects but did not have the means, whether that be money, status, or locality. Globalisation resulting in time-space compression as well as the increase in industrialisation, manufacturing techniques and transnational corporations has

allowed for products to become dramatically cheaper. Therefore, the ability for us to buy things is easier than ever, but has it caused depreciation in our perception of their beauty?

Glossary

Utilitarian design- Design that prioritizes function over form and other elements.

Time-space compression- the way the world is perceived to be smaller due to the increase in transport, communications, and capitalist processes.

References

Berger, J., 1972. Ways of Seeing. s.l.:Penguin Classics.

Yanagi, S., 2019. The Beauty of Everyday Things. s.l.:Penguin Classics.

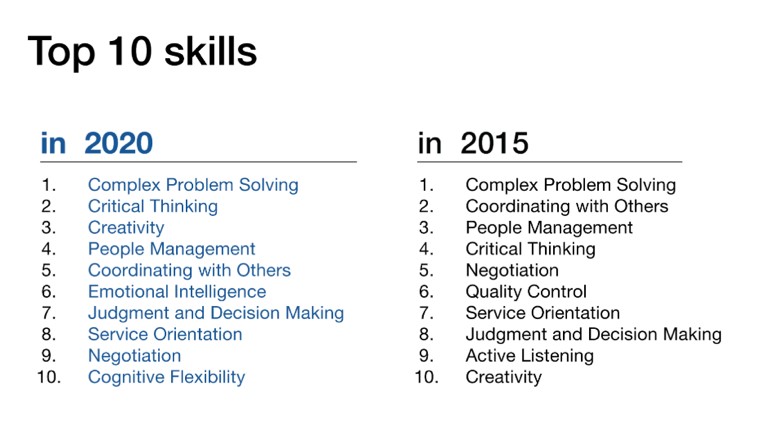

The aim at WHS is to equip students with the new skill set that they will require for the predicted ‘Fourth Industrial revolution 2020’ and to meet the shortage in UK Engineers, especially with women. We needed to change the approach to how Design and Technology is taught in response to a changing world.

The aim at WHS is to equip students with the new skill set that they will require for the predicted ‘Fourth Industrial revolution 2020’ and to meet the shortage in UK Engineers, especially with women. We needed to change the approach to how Design and Technology is taught in response to a changing world.

This was another valuable opportunity where the girls stood and presented their concepts. They responded extremely well to the questions from various delegates who were very impressed with their ideas. After their presentation a number of delegates had further conversations about how the ideas developed and took closer looks at the latest iterations developed in conjunction with DS Smith. A number of delegates were keen to see it progress and one in particular, Sara Nelson RGN from Healthy London Partnership based at the Evelina Hospital at St Thomas, was very interested in running a pilot at her clinic with the textiles monkey bag design created by Sascha. A great day was had by all.

This was another valuable opportunity where the girls stood and presented their concepts. They responded extremely well to the questions from various delegates who were very impressed with their ideas. After their presentation a number of delegates had further conversations about how the ideas developed and took closer looks at the latest iterations developed in conjunction with DS Smith. A number of delegates were keen to see it progress and one in particular, Sara Nelson RGN from Healthy London Partnership based at the Evelina Hospital at St Thomas, was very interested in running a pilot at her clinic with the textiles monkey bag design created by Sascha. A great day was had by all.