Chemistry teacher Marcus Patterson unpacks why initiatives at Wimbledon High School to carry through students’ sense of wonder about the world, from Primary science right through to Key Stage 4, are so important

Curiosity may have killed the proverbial cat, but for us humans, it has been, and I’m sure will continue to be, our raison d’être. From the gastronomic delights we enjoy in restaurants to the latest technological gadgets we now take for granted, curiosity and investigation have been behind them all.

In Key Stage 4, students deepen and develop their scientific knowledge and skills in preparation for their GCSE exams. Some further their education by studying science subjects at A Level. However, for others, the science they study at KS4 will be the only science education they get. So it is important that they are not only exposed to high quality teaching but that they remain enthusiastic and curious about the world around them. Because we want – no, need – our students to leave Wimbledon High School equipped to face future challenges and to come up with creative solutions to current and future problems with knowledge, reason, and zeal.

Fading fervour?

My experience, as well as the consensus more widely, suggests that students’ fervour for science start to dwindle at Key Stage 4. All children come to primary school with their own ideas and questions about science; how nature works, what energy is, what things are made of, as well as a litany of whys about everything else. During Key Stage 2 at WHS, students investigate the phenomena of living organisms, materials, Earth, space and forces. Their curiosity and eagerness is evident in their exercise books, which contain some outstanding work.

However, at Key Stage 4, that same sense of enthusiasm and wonder for science is much more difficult to see in students’ work. To be fair, students spend more time taking notes and sitting assessments than they probably did in primary school. However, the point remains: many students’ eagerness for science starts to wane, and learning science becomes a chore, based on learning content and skills simply to receive some hoped-for grade in the GCSEs.

To turn the tide in this seeming trend, Key Stage 3 has a vital role to play, as a bridge between the zestful, open, and wondrous world of primary school science and the more sophisticated, yet more sedate, world of Key Stage 4 Science. At Wimbledon High School, teachers have come up with some interesting and effective ways to help primary school students transition to science education at Key Stage 3, enabling KS3 Science to become a more effective bridge between Key Stages 2 and 4.

Extending enthusiasm

One opportunity is the taster lesson. In May, Alex Farrer brought her Year 6 Science students to work alongside Year 7 Science students in the Key Stage 3 Science Lab located in the STEAM tower of the Senior School. In the past year, Year 6 students have studied electricity and have collaborated with Year 7 students to investigate electricity and cells, and to build coin-cell batteries.

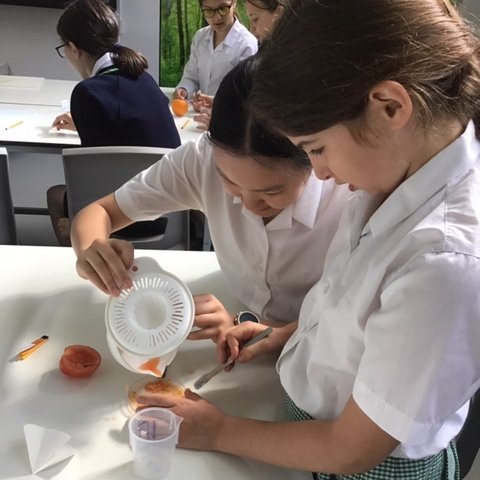

In addition, Year 5 students visited the Senior School Key Stage 3 Science Lab for a taster lesson during which they explored the world of chemical and physical changes. Both Years 5 and 6 taster sessions allowed students from the Junior School not only to see and experience how science education is done at KS3 in the Senior School, but also to reinforce and buoy the learning experiences they have had so far in science, giving students a sense of continuity. What they have learned so far continues to be explored, albeit a bit more deeply, at KS3. Such continuity allows students to maintain and further develop their curiosity and enthusiasm for science.

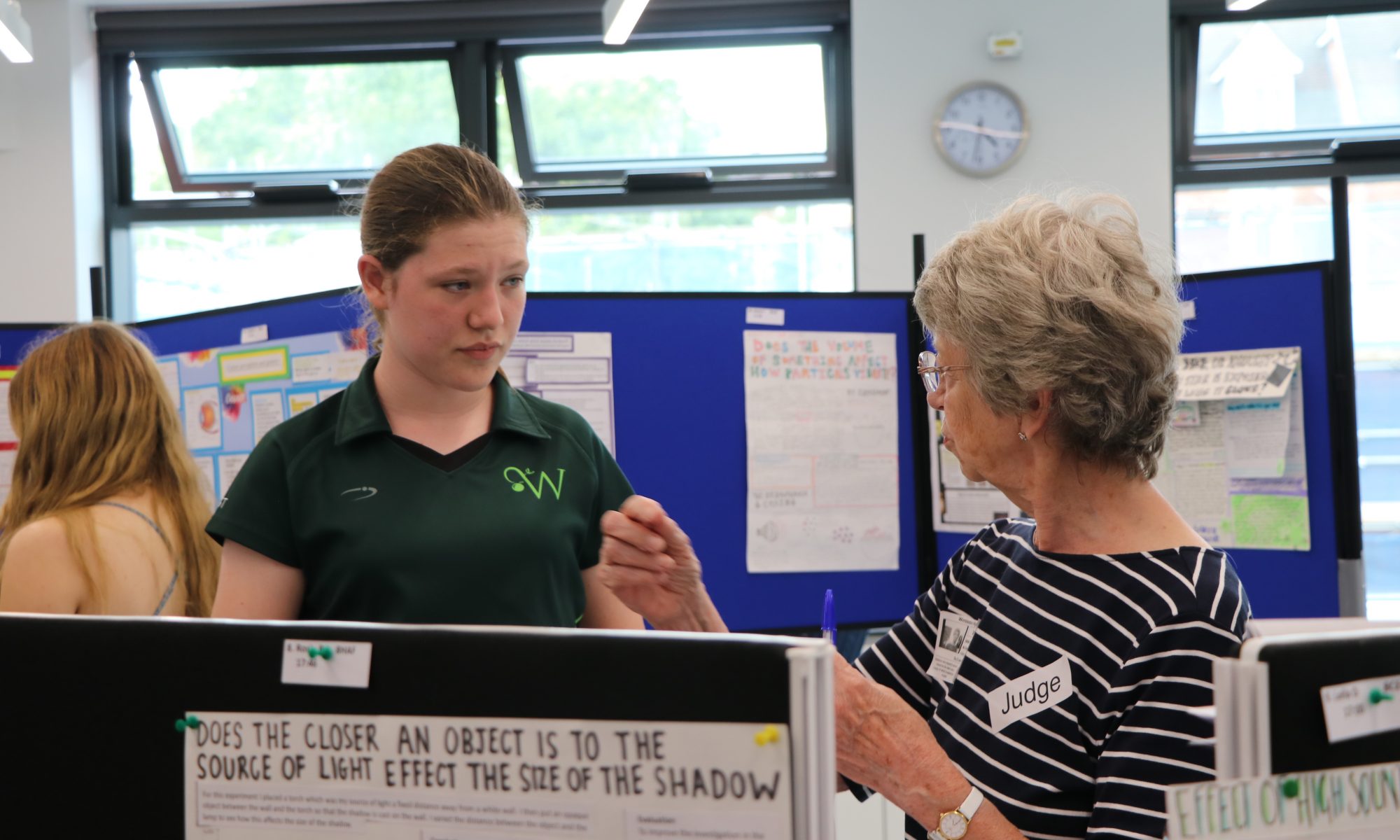

In Key Stage 3, students’ scientific knowledge and skills grow, and their ability to communicate scientifically is starting to develop. To give students an opportunity to apply what they have learned in interesting and creative ways, Year 8 Science students put on a Science Fair. They spent the last five weeks asking questions, coming up with hypotheses, and investigating the nature of light and sound. They presented their findings in a poster session and discussed their projects with judges, parents, teachers, and each other. Students were inquisitive and worked enthusiastically on their projects, and the results were consistently creative and superb.

Cultivating curiosity

As Key Stage 3 Science teachers, we can keep students wondering eagerly about the nature of the world around them as we encourage them to reflect upon and evaluate the answers to the questions they had before: are they satisfied, and what more do they want to know? Encouraging this type of self-reflection among students, whether through class discussions or a science journal, can do much to help them maintain that zealous and inquisitive momentum for science into and throughout their Key Stage 4 Science experience.

Just as Junior School students are given an opportunity to experience science at the Senior School, Key Stage 3 students could be given an opportunity to have taster lessons in Key Stage 4 science areas. They will come to see that the topics and themes they explored in KS3 continue to be explored at KS4, but their knowledge, understanding, and communication of science will become more sophisticated. Some of their previous questions will be answered, and then they will then have new questions. Our aim is to get them to seek the answers to those questions with the same zest and wonder as they had when they were in primary school. Exciting times are ahead!

Teacher support during the lesson is formative and needs to turn a spotlight on successes, hitches, failures, resilience, problems and solutions. For example, the teacher might interrupt learning briefly to point out that some groups have had a problem but after some frustrations, one pupil’s bright idea changed their fortunes. The other groups are then encouraged to refocus and to try to also find a good way to solve a specific problem. There might be a reason why problems are happening. Some groups may need some scaffolding or targeted questioning to help them think their way through hitches.

Teacher support during the lesson is formative and needs to turn a spotlight on successes, hitches, failures, resilience, problems and solutions. For example, the teacher might interrupt learning briefly to point out that some groups have had a problem but after some frustrations, one pupil’s bright idea changed their fortunes. The other groups are then encouraged to refocus and to try to also find a good way to solve a specific problem. There might be a reason why problems are happening. Some groups may need some scaffolding or targeted questioning to help them think their way through hitches.