Amy (Year 13) looks at the issues surrounding gentrification of an area and the impact this has on the value and cultural capital of an area.

Gentrification has often been seen as a contested and negatively connoted process; it is routinely blamed to be destroying the ‘souls’ and ‘hearts’ of many cities across the globe, with higher housing costs to increasingly globalised high streets acting as forces driving those less privileged out of historically culturally rich community areas. It can be seen as an oppressive mechanism which, in potentially adding fiscal value to an area, does so at the expense of cultural diversity.[1]

Gentrification is a term first created more than 50 years ago by the German-born British sociologist Ruth Glass to describe changes she observed in north London – but it is a phenomenon that has been at the heart of how cities evolve for centuries. Cambridge dictionary defines the term as ‘the process by which a place, especially part of a city, changes from being a poor area to a richer one, where people from a higher social class live.’[2] It is an important factor in the change and transformation of urban areas. However, whether it really eradicates poverty is subject to lively debate.

In London especially, gentrification characterises economic and demographic changes as the predominantly middle-class citizens settle in areas often occupied by high percentages of ethnic minority residents, who are often priced out of the new ‘improved’ areas. Not only does it have significant negative impact on smaller community areas, it also sends ripples throughout the rest of the country and down the class hierarchy.

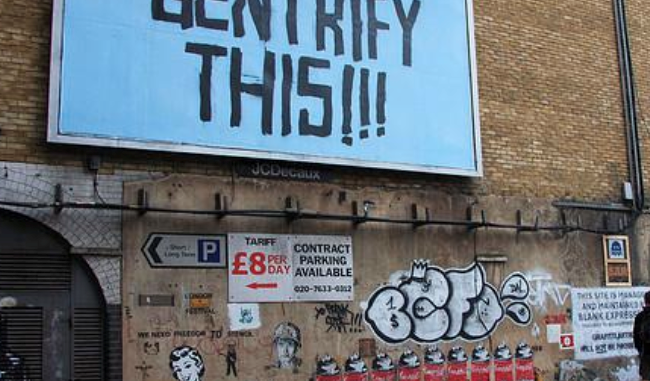

Much resistance has been seen from those who see the process as an antagonised way of removing character and community from an area. In particular, estate agents and property developers are subject to this disapproval, with many campaigners vocal against their activities, given they seek to make money from attracting new, richer residents. Especially extreme campaigns such as the 200 anti-gentrification and housing campaigners that disrupted the beginning of the annual Property Awards in 2016 reveal the strong opinions many people have towards the process of gentrification.

When examining this change in London, it is important to inspect the history and background of the city itself. Gentrification is not a new process to the city, beginning in the 1960s when bits of the run-down, old post-war city attracted adventurous young architects who started doing up often cheaper, damaged, Georgian squares. The process is deeply ironic, as these forces of change accused of ruining London are products of its revitalisation.

Decades ago London was still recovering from detrimental damage done during World War 2. The population of inner London was still attempting to recover to its pre-war importance. At this point, it wasn’t the wealthy being the cause of change in the area but skilled manual workers seeking cheap and convenient land, headed for ‘the New Towns’ in the 1950s.

By the start of the 2000s however, London’s dynamic had completely changed. London had become an influential source of economic growth, catalysed by its ability to generate money from its ‘turbo-charged’ Square Mile. Increased profit immensely amplified the attractivity of London, in turn increasing the demand of space in the city. It is regularly said that ‘demand for space is the seed of gentrification’[3], and a failure to meet that demand is what stimulates the growth of it. London is a prime example of this. Hugely inflated property prices are a certain cost of gentrification, and this can be seen all throughout London. The average house price in Hackney, and area renowned for its influence of gentrification, has increased by 489% in the last two decades, up from £91,000 in 1998 to £536,000 in 2018. This directly drives out many ethnic minorities and those living on low income or relying on government benefits to afford housing costs.

The standard picture of gentrification is that new arrivals benefit greatly from gentrification at the expense of lower-income residents. This picture is often true in many cases. New arrivals to a community often get stylish housing and all of the expensive accessories of life in a trendy urban neighbourhood (boutiques, bookstores, coffee shops, clubs and more) that they can afford. While long-time residents may benefit initially from cleaner, safer streets and better schools, they are eventually priced out of renting or buying. As the new arrivals impose their culture on the neighbourhood, lower-income residents become economically and socially marginalized. This can lead to resentment and community conflict that feeds racial and class tensions. Ultimately as lower-class members of the community move out this can induce loss of social and racial diversity. Rowland Atkinson, a member of the ERSC centre for research describes it as ‘a destructive and divisive process that has been aided by capital disinvestment to the detriment of poorer groups in cities.’[4]

However, should gentrification really be held accountable for the unacceptable level of poverty in London? Assertions that it is ‘pushing out’ the deprived of the city often look less persuasive when examining the figures of social housing which still exist in classic ‘gentrified’ areas of north London. In Camden, 35% of all housing is for social rent, in Islington it’s 42% and in Hackney, 44%. Although poverty rates have fallen in those boroughs, the absolute numbers of poor people (people living on the reliance of government benefits) remain high.

Although there are many deservingly negative outlooks on the consequences of gentrification, assumptions should not always be made to antagonise the process. For example, middle class pressure often leads to improvement in community features such as modernised and beautified public buildings and spaces. As the property tax base increases, so does funding to local public schools. Jobs arrive with the increased construction activity and new retail and service businesses, and crime rates habitually decline.

Edward Clarke of the UK urban policy research company Centre for Cities writes that the debate should not be reduced to ‘a simple battle between plucky communities and greedy gentrifies’, emphasising that this ‘fails to recognise that the roles and functions of urban neighbourhoods have always changed over time and within a city’ or to acknowledge that gentrifying ‘new work businesses can create new jobs and improve wages in many fields.[5]

Clarke concludes in general that the real roots of the problems that come with thriving urban economies are ultimately down to “poor city management”. He argues that to improve this it requires better skills training for local people, more planning and tax-raising powers to be devolved to local politicians and more land, including a small portion of green belt, being made available for building.

Ultimately gentrification, as a form of change and transformation in urban areas, is an issue that has been going on for decades. Although it potentially brings improvement to the appearance and functionality of urban environments, the problems created by this process must be addressed; failing to do so will result in places like London becoming so unaffordable they will begin to deteriorate – not only in potential economic value, but also in cultural capital. The process often exacerbates inequality on a local scale and drives out the cultural diversity that can so often be found at the heart of London’s communities.

Bibliography

Glass, R. (1964). London: Aspects of Change. London: MacGibbon & Kee

Hill, D. (2016). Let’s get our gentrification story straight. London: Guardian

Dr Atkinson, R. (2002). Does Gentrification help or harm urban neighbourhoods? An assessment of the evidence-base in the context of the new urban agenda. CNR Paper 5

Clarke, E. (2016). In defence of gentrification. London: Centre for Cities

[1] See https://newdream.org/blog/consumption-gentrification-and-you

[2] See https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/gentrification#:~:text=Meaning%20of%20gentrification%20in%20English&text=the%20process%20by%20which%20a,of%20East%20London%20by%20gentrification.

[3] See https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/davehillblog/2016/oct/24/lets-get-our-gentrification-story-straight#:~:text=Demand%20for%20space%20is%20the,were%20born%20%E2%80%93%20look%20further%20afield.

[4] See http://www.urbancenter.utoronto.ca/pdfs/curp/CNR_Getrifrication-Help-or-.pdf

[5] See https://www.centreforcities.org/blog/in-defence-of-gentrification/