Holly Beckwith, Teacher of History and Politics at WHS, explains how the History and English departments are using a small-scale action research project to try and rethink the way in which analytical writing is taught at Key Stage 3.

The age-old question for history teachers: how do we get our pupils to produce effective written analysis? It is a question we regularly grapple with as a department. Constructing and sustaining arguments is at the centre of what we do as Historians and analytical writing is thus at the core of our teaching of the discipline. But it has not always been an easy task for history practitioners to get pupils to achieve this, even over a whole key stage.

Through published discourse, history teachers have explored the ways in which we can teach pupils to produce argued causal explanations in writing (Laffin, 2000; Hammond, 2002; Chapman, 2003; Counsell, 2004; Pate and Evans, 2007; Fordham, 2007). Extended writing has been seen as an important pedagogical tool in developing pupils’ causal reasoning as it necessitates thinking about the organisation, arrangement and relative importance of causes.

In 2003, History teacher Mary Bakalis theorised pupils’ difficulty with writing as a difficulty with history. She posited that writing is both a form of thinking and a tool for thinking and, therefore, that historical understanding is shaped and expressed by writing. Rather than viewing writing as a skill that one acquires through history, Bakalis saw writing as part of the process of historical reasoning and thinking. Through an analysis of her own Year 7 pupils’ essays, she noticed that pupils had often failed to see the relevance of a fact in relation to a question. She realised that pupils thought that history was merely an activity of stating facts rather than using facts to construct an argument.

As a solution to similar observations in pupils’ writing, history teachers have used various forms of scaffolding to help pupils construct arguments. This includes the well-known PEE tool, which was advocated by genre theorists and cross-curricular literary initiatives as put forward by, for example, Wray and Lewis (1994), and has since been used widely in History and English departments nationwide, including ours at Wimbledon High. The concept of PEE (point, evidence, explanation) is simple and therefore a helpful tool for teaching paragraph structure. It gives pupils security in knowing how to organise their knowledge on a page.

Figure 1: PEE – Point, Evidence, Explanation

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing.

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing.

After reflecting on this research conducted by History teachers as a department, we started to consider that encouraging our pupils to use structural devices to help pupils’ historical writing may not be very purposeful if divorced from getting pupils to see the function and role of arguments in the discipline of history itself. Through discussions with the English department, who have also used the PEE tool in their teaching, we realised we shared similar concerns.

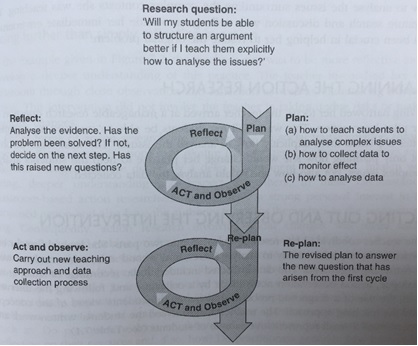

Not satisfied with simply holding these, we decided to do something about it and have since embarked on a piece of action research with the English department. Action research is interested in finding solutions to problems to produce better outcomes in education and involves a continual cycle of planning, action, observation and reflection such as Figure 2 below illustrates.

We started our first cycle of our piece of small-scale research last term teaching analytical writing to classes using two different lesson sequences: one which teaches pupils PEE and one which omits this.

We then compared the writing produced by these classes to identify any noticeable differences and structured our reflections around four questions:

1. How has the experience of teaching and learning been different to previous experience, and why?

2. How have students responded to the new method?

3. How far has the intervention resulted in a different approach to analytical writing so far?

4. What are our next steps – what went well, and what needs adjusting?

Figure 2: The action research spiral (Wilson, 2017, p. 113)

Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.

Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.

The first research cycle has thus been a worthwhile collaborative reflection on our teaching practice in the pursuit of improving our pupils’ historical and literary analysis. It has given us some insights which we’re looking to develop further as we head into the second term of the academic year.

–