Gaining publicity following Youtuber Logan Paul’s video filmed in Aokigahara, one of Japan’s suicide hotspots, the extremely high suicide rate in Japan has been featured increasingly in Western news. In this article, Jess Marrais aims to explore possible historical and traditional reasons for both Japan and Western attitudes towards suicide.

The world of YouTube and social media crossed over into mainstream media on 1st January 2018 following a video uploaded by popular YouTuber, Logan Paul. Paul and a group of friends, while traveling around Japan, decided to film a video in ‘Aokigahara’, a forest at the base of Mt Fuji, famous as the second most popular suicide location in the world. The video, which has since been taken down, showed graphic images of an unknown man who had recently hanged himself, and Paul and the rest of his party were shown to joke and trivialise the forest and all that it represents.

Unsurprisingly, Paul received a lot of backlash, as did YouTube for their lack of response in regards to the video itself. This whole situation has restarted a discussion into Japanese suicide rates, both online and in mainstream media sources such as the BBC.

In the discussions surrounding the problem, I fear that little has been said in the UK about the cultural attitudes in Japan towards suicide, and how drastically they conflict with the historical beliefs entrenched in our own culture.

In Christianity, suicide is seen as one of the ultimate sins- to kill oneself is to play God, to decide when a soul should leave the Earth, and breaks one of the 10 Commandments (‘Thou shall not murder’). Historically, those victim to suicide were forbidden from having a Christian funeral or burial, and it was believed that their souls would have no access to heaven. As a result of this, it makes sense that in Christian countries suicide is frowned upon. We in the West view the high suicide rate in Japan, and other East-Asian countries, through our own cultural understanding; while in actual fact, the problem should be seen within the context of the cultural and historical setting of the countries themselves.

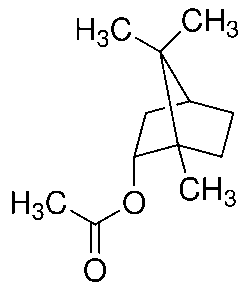

In Japan, the history of the samurai plays a large role in attitudes towards suicide. The samurai (military nobility) had monopoly over early Japan, and they lived by the code of ‘Bushido’- moral values emphasising honour. One of the core values of Bushido was that of ‘seppuku’- should a samurai lose in battle or bring dishonour to his family or shogun (feudal lord), he must kill himself by slitting open his stomach with his own sword in order to regain his- and his family’s – honour in death. Due to the prominent role the samurai played in Japanese society, this idea of killing oneself to regain honour seeped into all aspects of society, thanks to personal and familial honour being a central part of Japanese values, even today.

More recently, this warrior attitude to death can be seen in the famous World War II ‘kamikaze’ pilots- pilots who purposefully crashed their planes, killing themselves and destroying their targets (usually Allied ships). These pilots were typically young, and motivated by the prospect of bringing honour to their family and Emperor in death. During the war, 3,682 kamikaze pilots died, spurred on by the samurai code of Bushido.

In modern day, suicide is seen by many in Japan as taking responsibility. Suicide rates in Japan soared after the 2008 financial crash, reaching their highest at the end of the 2011 economic year. Current statistics say around 30,000 Japanese people of all ages commit suicide each year, as opposed to 6,600 per year in the UK. Increasing numbers of Japan’s aging population (those over 65) are turning to suicide to relieve their family of the burden of caring for them. Some cases even say of unemployed men killing themselves to enable their family to claim their life insurance, in contrast to the UK where suicide prevents life insurance being from claimed. Regardless of the end of the samurai era and the Second World War, the ingrained mentality of honour drives thousands of people in Japan to end their own lives, motivated not only by desperation, but also the desire to do the right thing.

If anything can be taken away from this, it is to view stories and events from the cultural context within which they occur. While suicide is a tragic occurrence regardless of the country/culture in which it happens, social pressures and upbringing can – whether we are aware of it or not – influence a person’s actions. If this lesson can be carried forward to different cultures and stories, we will find ourselves in a world far more understanding and less judgemental than our current one.

Follow History Twitter: @History_WHS

Suicide hotlines:

- PAPYRUS: support for teenagers and young adults who are feeling suicidal – 0800 068 41 41

Further reading: