Steph Harel, Acting Head of Geography at WHS, explores the journal article ‘Developing enquiry through questioning’

Wood, P. (2006) Developing enquiry through questioning. Teaching Geography, 31(2), 76-78.

“Any student wising to develop their capacity to enquire geographically requires a clear capacity to question” (Wood, 2006; p. 78).

Many classrooms, and even national strategies, focus on teachers as the main questioners; however, if students are to develop an independence in their work they must gain experiences which allow an opportunity to play a central role in framing questions of interest.

Wood accurately argues that students need to develop their questioning skills if they are to act as autonomous enquirers. His valuable exploration into different ‘levels’ of questioning in Geography highlights meaningful ways in which to support students to develop their own capacity for independent questioning:

1. Simple questioning: Simple questioning games can be used to develop and sharpen students’ questioning skills. For example, when revising a physical geography topic, students are given a post-it note with a keyword written on it, which they stick to their foreheads. Students then pose each other ‘yes’ ‘no’ questions to decipher which process they have been allocated.

2. Questions to compare: Students are asked to develop questions which will produce a clear and detailed comparison. For example, students studying tectonic hazards might explore two case studies, one from an AC and one from an LIDC, and are asked to compare their volcanic eruptions by posing questions. Importantly, students then reflect on why they have chosen their questions.

3. Questions to enquire: Wood uses an example of a KS3 class, who recently completed a unit on agriculture. Students were prompted to consider the underlying patterns and processes they studied and asked to formulate five questions they would use to investigate the agriculture of India. For example, “How does landscape and climate affect farming in India”? I was particularly struck by Wood’s focus on the importance of recognising that enquiry questions can lead to ‘dead-end’ responses, and that learning and understanding is not a simple or linear process.

4. Questions to research: When students have developed a questioning capability, they can be given a large amount of autonomy in both framing and researching questions. Wood explores this idea in KS5 Geography teaching, with students studying the global economy. Students were offered a new context in which to explore the changing economic fortunes of two contrasting locations and the opportunity to decide on questions they felt were pertinent to ask. The process culminated in a written report, which demonstrated deep and critical understanding of the information researched.

As an educator, it is my belief that the geography classroom is an ideal environment for developing the use of self-questioning. I found huge value in Wood’s article, which argues that it is crucial that teachers not only learn how to pose their own questions to greatest effect, but also guide and support students in developing their own enquiries about the world around them. “By focusing on the student as questioner, we can help them become more active, reflective learners, and this can only help in developing active, critical classrooms where quality geography [my emphasis] can blossom” (Wood, 2006; p. 78).

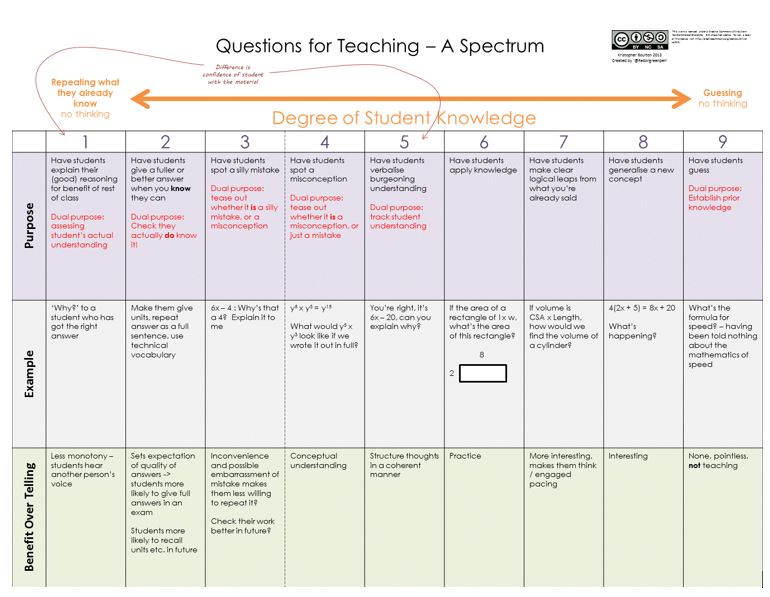

addresses that the question is not why questions are better, it is when. He concluded that: ‘questions can be very effective tools of teaching, but they must be used with incredible care.’ A very structured grid of various question types concluded by him and another blogger can be found here:

addresses that the question is not why questions are better, it is when. He concluded that: ‘questions can be very effective tools of teaching, but they must be used with incredible care.’ A very structured grid of various question types concluded by him and another blogger can be found here: