Dr Clare Roper, Director of Science, Technology and Engineering at WHS, looks at how advances in information technology have removed the barriers that often limit the scope for school students to embark on their own innovative authentic scientific research.

I was sitting in a lecture at Oxford University about 18 months ago when it suddenly became clear to me that the factor most often restricting school students from undertaking their own authentic research had evaporated and was no longer an issue.

Classroom science experiments commonly involve replicating known scientific phenomena to backup discoveries that are well documented in the scientific literature. Unfortunately, quite often we cannot even so much as replicate the data from a science textbook in a school laboratory because the data collection is too complex. Instead, we might explore the scientific process taken by a research group as we unpack a beautiful classic experiment and marvel at their discovery and how it has shaped our understanding of scientific concepts . A personal favourite is the magically simple experiment of Meselson and Stahl which elucidated how exact copies of DNA are created each time a new cell is formed [1]. At the end of a lesson exploring their experiment, it is customary to have a look at photographs of the scientists and perhaps consider how they may have come up with their experimental design.

I often ponder whilst looking at a black and white photograph of a scientist with his unrecognisable equipment, how this person might be perceived by the students sitting in front of me in our shiny new STEAM tower. Is this what being a scientist entails? Even after removing the stereotype of the person themselves, there is the barrier of the often sophisticated machinery and the hours of patient work required to collect sufficient data to make meaningful conclusions. I have no doubt that although we can enjoy the simplicity of their experiments in class, it surely reinforces the notion that novel scientific research is something inaccessible and unattractive to many school students.

In sport, there are countless role models of young athletes competing on the world stage, with celebrated successes at their local schools. The same can be said of talented young actors, artists, musicians and even activists and politicians. But try to think of a brilliant young scientist who has gone on to become a world leader having had the opportunity to hone their skills and find their path whilst at school. The fantastic news that two leading female scientists, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, have just been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work on genome editing [2] will certainly go a long way to inspiring more female scientists to dream big. However, like most leading scientists, their first taste of authentic research came after entering university and most are often only recognised much later in life.

The good news is that a growing number of passionate science teachers have teamed up with academics and a variety of institutions to provide opportunities for young scientists. Most research projects require access to expensive machinery or software that is beyond the reach of a school science department budget, and even those projects that are possible often tend to focus more on one or two aspects of the scientific process and cannot give the students carte blanche to explore their own curiosities because of time or cost constraints. Nevertheless at WHS we jumped on board and our students have benefitted hugely from projects including ORBYTS, and IRIS.

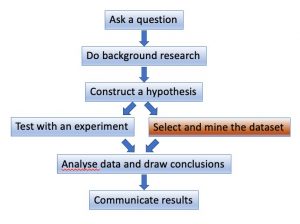

While I was in that lecture at Oxford that I suddenly realised that the missing ingredient that has recently evaporated was the need for the sophisticated machinery, and along with it, the prohibitive costs, and lengthy time required to collect data. The lecture was given by Prof Stephen Roberts, who specialises in machine learning and data analysis. Talking to him after his presentation about how ‘big data’ has shifted the emphasis in many university research labs from classic experimental design and data collection, towards a notion of data mining confirmed for me that the vast array of publicly available big datasets means that this modern approach to the scientific method makes novel research a feasible venture for all school students.

Scientific research using a data mining approach is exciting in that the data already exists, replacing the need for laborious experimental testing. The phenomenal progress in the field of artificial intelligence has meant that individual lab-bench experimental datasets are being replaced with enormous datasets which bring with them greater authenticity to the results, and also the ability to explore an expansive array of research questions that were never possible before. Data is amassing quicker than tertiary-level scientists can analyse it, and so the potential for school students to pose innovative research questions of these big datasets is not only boundless, but also a welcome and untapped asset in the quest to answer the world’s most pressing scientific questions.

Novel research already on the go at WHS

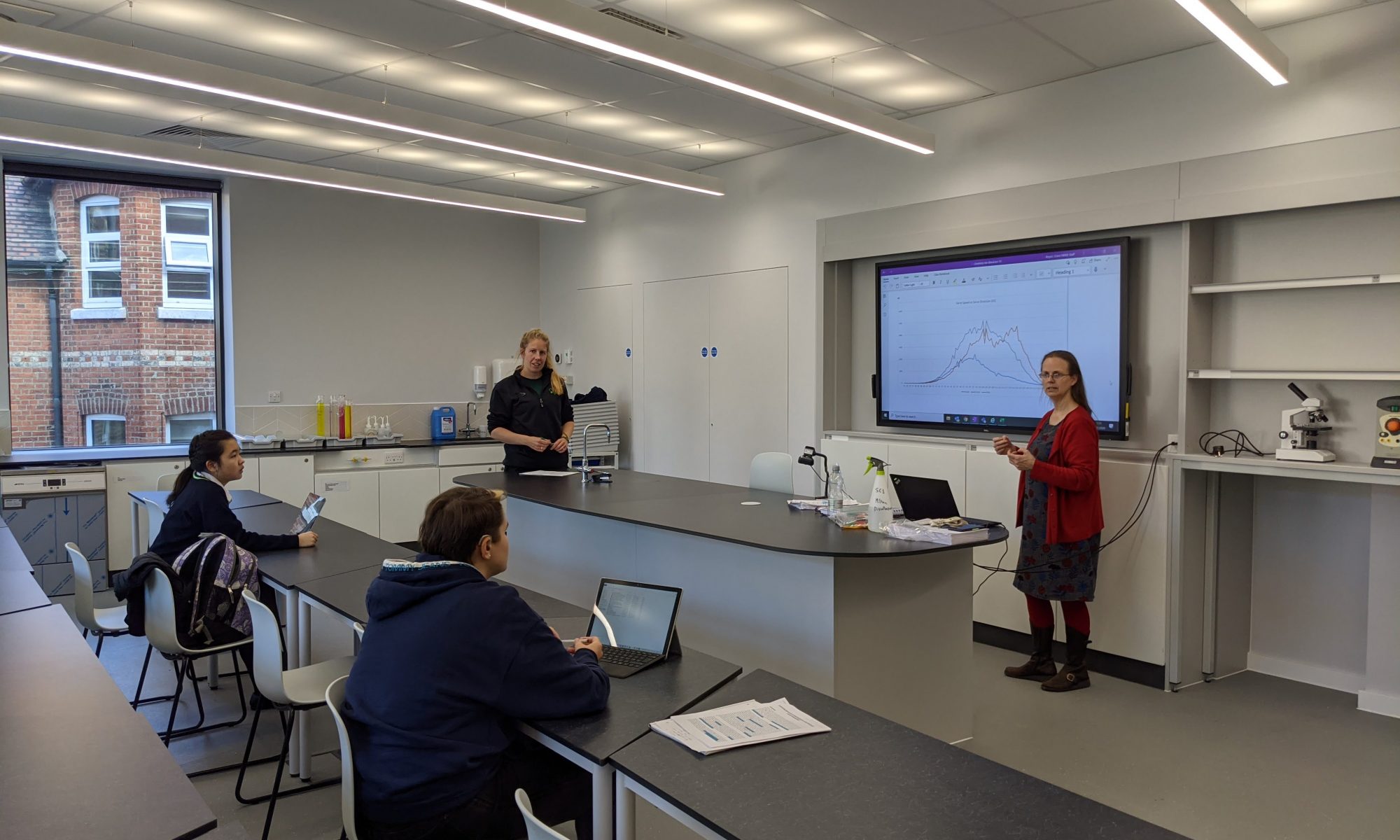

We have already embarked on this exciting journey. Our first venture has been a collaboration with AELTC and IBM, who have kindly provided us with access to a huge dataset from the Wimbledon Tennis Championships. Like all great research groups, and in true STEAM+ style, we bring together different skills. The creative powers of the unclouded vision of the young scientists, supported by our Director of Sport Ms Coutts-Wood’s expertise in sport science and my experience of data analysis, has meant than we are in the final stages of publishing our first scientific paper on the impact of serve speed on winning the point. How apt!

Two more groups started during lockdown. One group under the supervision of Ms McGovern (Head of Chemistry) in collaboration with the University of Bristol, has recently received a special award for their research on Air Pollution. The other group are drawing on the expertise at the European Bioinformatics Institute in Heidelberg, Germany and the Wellcome Trust Genome Campus outside Cambridge. Their research questions range from discovering the differences in proteins associated with immune function in red and grey squirrels, to determining which mammalian species do not have attachment sites for the coronavirus (SARS CoV-2) spike protein. These bioinformatics projects will be launched on the EBI website soon to allow other schools to join in as well. Watch this space!

Just as the new STEAM tower is about to open, so too are new exciting possibilities for our young imaginative scientists at WHS.

References

[1] https://magazine.caltech.edu/post/the-most-beautiful-experiment

[2] https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2020/press-release/

Alongside high-quality provision in lessons, the academic stretch programme challenges our learners throughout the school.

Alongside high-quality provision in lessons, the academic stretch programme challenges our learners throughout the school. Our robust Explore and Rosewell lecture series welcomes external speakers to challenge and provoke those girls in Years 9 to 13 to think more deeply both within and without their subject specialism. Parents, teachers and partner schools are welcome at these lectures. Our external speakers have included: Janet Henry, Chief Global Economist for HSBC, “Diverging fortunes”; “In conversation with” Gillian Clark, poet, playwright,

Our robust Explore and Rosewell lecture series welcomes external speakers to challenge and provoke those girls in Years 9 to 13 to think more deeply both within and without their subject specialism. Parents, teachers and partner schools are welcome at these lectures. Our external speakers have included: Janet Henry, Chief Global Economist for HSBC, “Diverging fortunes”; “In conversation with” Gillian Clark, poet, playwright,  editor, broadcaster; Prof Vicky Neale, Whitehead lecturer at the Mathematical Institute, “Closing the Gap, the quest to understand prime numbers”; Dr Guy Sutton, “Mind and brain in the 21st Century”.

editor, broadcaster; Prof Vicky Neale, Whitehead lecturer at the Mathematical Institute, “Closing the Gap, the quest to understand prime numbers”; Dr Guy Sutton, “Mind and brain in the 21st Century”.

A discussion of “The Lazy Teacher’s Handbook” by Jim Smith drew the following comments:

A discussion of “The Lazy Teacher’s Handbook” by Jim Smith drew the following comments: “Independent Thinking” by Ian Gilbert elicited the following:

“Independent Thinking” by Ian Gilbert elicited the following:

That’s the important thing isn’t it? Being right. Now, you have evidence backing your own view. You are not the only person who thinks this way. Other people important enough to be published in some medium think this way. Therefore, they must be right and you must be right. Moreover, all you see is the same information reiterated in your News feed, Instagram account, or amongst your friends. This corroborates your view. The opinion you had which was a small delicate thing is growing and hardening, becoming a wall to keep your psyche safe from thoughts that it assumes might damage it. Your confidence grows. Your surety of opinion flourishes.

That’s the important thing isn’t it? Being right. Now, you have evidence backing your own view. You are not the only person who thinks this way. Other people important enough to be published in some medium think this way. Therefore, they must be right and you must be right. Moreover, all you see is the same information reiterated in your News feed, Instagram account, or amongst your friends. This corroborates your view. The opinion you had which was a small delicate thing is growing and hardening, becoming a wall to keep your psyche safe from thoughts that it assumes might damage it. Your confidence grows. Your surety of opinion flourishes.

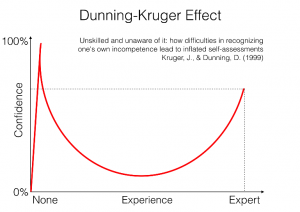

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If we consider the Dunning-Kruger effect (demonstrated on the diagram to the right) we might agree. The principle is that ‘knowledge without sufficient experience can lead to an overestimation of ability’. It is no surprise that Donald Trump has been nicknamed the ‘Dunning-Kruger President’ in articles by the New York Times, Bloomberg, and the Independent. I recall an interview where he tries to explain uranium to his audience:

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If we consider the Dunning-Kruger effect (demonstrated on the diagram to the right) we might agree. The principle is that ‘knowledge without sufficient experience can lead to an overestimation of ability’. It is no surprise that Donald Trump has been nicknamed the ‘Dunning-Kruger President’ in articles by the New York Times, Bloomberg, and the Independent. I recall an interview where he tries to explain uranium to his audience: