Emma Ferraris in Year 12 gives us an insight into the new gene editing technology of the past 30 years and the potential it has for changing the world of medicine and how we view our species.

In the past 30 years editing of the human genome has evolved and improved leaps and bounds, most notably with the discovery of the new technology Crispr, which, since 2012 has been available and used by scientists to manipulate the genome.

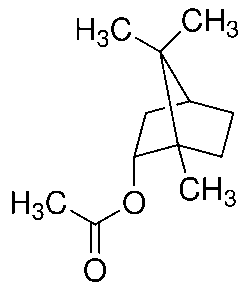

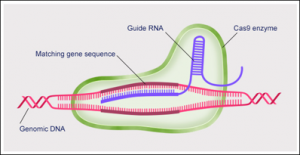

Crispr in itself is a short section of repeated DNA found in the genomes of bacteria and other microorganisms, but when coupled with an enzyme such as Cas-9, the technology enables geneticists to edit part of the human genome by cutting sections at a specific place and removing or adding new strings of DNA. This uses RNA which acts as a marker to ensure the Cas-9 enzyme edits the sequence in the right place.

As a result this technology is the most precise and versatile method of manipulating genetics to date and moreover can be purchased for around $60 – far cheaper than any other known method for DNA splicing. Hence unsurprisingly there has been much buzz and scruple around the new technology in the scientific world.

So, what will this gene editing mean for the future of medicine? And how will this affect you?

There is a whole host of possible uses for this new technology, including its capacity for combatting diseases, viruses and mutations in humans, as well as its ability to edit the genome of specific cells in the body.

On a small scale Crispr technology has been used successfully to edit the HIV virus out of the cells of rats. In 2016, Kamel Khalili, director of the Comprehensive NeuroAIDS Center at Temple University, managed to edit out around 50% of the HIV virus that was present in 99% of the rats cells. This success rate seems very hopeful for the future of the removal of this virus from both animals and humans, indeed Khalili himself commented that “CRISPR may be more convenient for gene editing than the prior gene editing tools used.” However, this is only one step, albeit an important one, in the process of using Crispr to actually edit out the virus from a human patient’s cells.

On a larger scale Crispr has, in the past year, been used in immunotherapy to treat certain cancers. Using Crispr, Michel Sadelain, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, was able to remove T-cells (a certain type of white blood cell which play a part in the immune system) from the blood and edit them using Crispr so that they were better able to recognise the antigens (individualised markers) on cancerous cells. As a result the T-cells could locate and destroy the tumour much more easily and with greater effect.

Similarly in Pennsylvania this month, scientists began an experiment in not only making the T-cells better able to locate the mutating cells, but also edit out two of the genes in the immune cell that mean they are better able to actually attack the tumour. This ex vivo (out of glass) therapy is also a lot safer than injection of Crispr straight into the blood as this sometimes causes a negative immune reaction.

Possibly most like a science-fiction plot, Crispr also has the capacity in the future to edit human genes and indeed the DNA in reproductive cells so that a new breed of eugenics could be on the horizon.

James J. Lee, a researcher at University of Minnesota said “In my opinion, CRISPR could in principle be used to boost the expected intelligence of an embryo by a considerable amount.” This theory is both exciting but has also unsurprisingly sparked many bioethnic debates in recent years, especially after a study in China 2015 used Crispr to edit a human embryo.

Whether or not you agree with the ethics, the prospects of designer babies and the perfect genetically engineered human soldier, which were once merely fictional, suddenly seem like a possible reality if the editing of human embryos continues to improve.

Without a doubt there are many benefits of this technology which in the next decades will become increasingly used by the biomedical field in treatments for diseases and viruses in humans and animals. The potentially unethical and dehumanising effects of DNA editing are much more obscure, so it is the future generation’s responsibility to ensure the use of Crispr remains purely in the interest of scientific improvement.

Follow the WHS Biology department on Twitter: @Biology_WHS

lp to discover how many parents and pupils you have in your class with scientific interests and skills.

lp to discover how many parents and pupils you have in your class with scientific interests and skills.