It’s hard to picture a world without the stunning landscapes of Antarctica and the Amazon rainforest. It’s even harder once you are aware of the many complex and vital roles these ecosystems play. They not only maintain the balance in the earth’s climate and systems, but also serve and protect human populations, even those who live thousands of kilometres away. In this essay, I will explore the vast quantity of reasons why both of these ecosystems are crucial to planet Earth and deliberate over the need of preserving both Antarctica and the Amazon.

Antarctica is a truly unique place. It is the fifth-largest continent, spanning almost one-fifth of the Southern Hemisphere. Although, there are no permanent inhabitants of the area, nor are there any countries. One may think that this must diminish its importance, but it does not take away from the essential part it plays for Earth at all.

Antarctica is almost completely covered by ice. Dominating the region, the Antarctic Ice sheet covers 19 million km² at its peak in winter. Ice, due to its hue, reflects solar energy back into the atmosphere, helping to regulate temperatures in the process known as the albedo effect. Due to increased temperatures, this ice is melting at an alarming rate of 150 billion tonnes a year, with no signs of slowing (NASA, 2024). This decreases the effect, causing solar radiation to remain on the Earth. This warms the globe further, causing even more melting of ice, ending in a vicious positive feedback loop. Antarctica has shown to be particularly vulnerable to rising temperatures, given that it has warmed nearly four times faster than the rest of the globe since 1979 (Rantanen, M., Karpechko, A.Y., Lipponen, A. et al., 2022). This illustrates the pressing importance of preserving this area and reducing our greenhouse gas emissions.

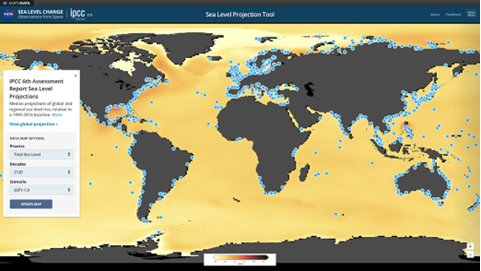

Similarly, as ice melts, there is an increased volume of water in oceans. This affects the entire globe. Firstly, 40% of the world’s population live within 100km of a coastline, and with every rise in sea levels, these areas become more and more at risk of flooding, or even being completely submerged underwater. This not only displaces people, but also damages infrastructure vital for transport, jobs, or even survival. The image below demonstrates areas that will be affected in the next century under even the optimistic, very low emissions scenario.

Those who live further inland aren’t left undisturbed. The billions of people who have had their homes destroyed will need to move somewhere, most likely to inland areas. This will create issues of overpopulation, which in turn leads to conflict over scarce resources. Ice sheet melting will not only affect countries physically and socially, but also economically. If there is no adaptation to the changes that will happen, global costs of incremental sea level rise from Antarctic Ice sheet melting are US$180 billion per year in 2050. In 2100, this will rise even more to US$1.04 trillion per year (Dietz and Koninx, 2022). In terms of the Amazon, increased immigration to inland areas could lead to flooding of the rivers and further deforestation in the rainforest to house new people, therefore impacting the entire region.

Small island developing states tend to be the most affected. Under the same scenario, in the mid-century (2040-2060) era, the Marshall Islands will have to pay costs representing 42.01% of their GDP, and furthermore, the Maldives will have to pay a shocking 53.39% (Dietz and Koninx, 2022). Despite making little contribution to carbon production, these countries will pay the biggest price. The Marshall Islands has pledged to reduce their carbon impact to net zero by 2050, and in 2023, they emitted only 3.9T of carbon per person. The Maldives also emitted 3.9T per person. In comparison, the United States and Canada emitted 14.3Tpp and 14Tpp respectively (Ritchie et al. 2023).

Antarctica also helps us understand the past and present of planet Earth. The Antarctic ice sheet is over 4 kilometers thick, and within it there is up to a million years worth of history. Scientists can drill down into the ice, producing huge ice cores, the longest of which being 2 miles long. They analyse gas bubbles and particles trapped in the ice, which can reveal past events that occurred, such as volcanic eruptions. The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) discovered the hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica in 1985 through studying the continent, which critically shaped the world, as it made scientists and the general public aware of it, and allowed us to find the information needed to help repair it.

Yet we cannot forget the absolutely critical role the Amazon plays on a local, national and global scale. The Amazon rainforest covers 7 million square kilometers, housing immense forests, winding rivers and 47 million people, of which over 2 million are from indigenous tribes. (WWF, 2022). The forest, which accounts for 97% of the land area, acts as a global carbon sink. From 2001-2021, Amazonian trees sequestered roughly 1.5 bn tonnes of carbon each year, which is equal to 4% of global fossil fuel emissions. In addition to this, there are roughly 200 billion tonnes of carbon stored within the Amazon ecosystem, both above and below ground. (Harris et al. 2021). This regulates the global climate and supports life across the planet.

This is changing. The Amazon has been a carbon emitter in recent years, due to mass deforestation for farming and unsustainable resource extraction. Trees are burnt, releasing huge quantities of CO2 that has been stored in the vegetation over many years. Since 2001, the Amazon has emitted 13% more each year than it absorbed, enhancing the greenhouse effect and therefore global warming (The Economist, 2022). Part of the reason for Antarctica’s rapid ice loss is due to the Amazon becoming a carbon source rather than sink.

The 2.2 million indigenous people who call the Amazon their home rely on it to live. These groups have lived on the land for thousands of years, living in harmony with the rainforest, taking only what they need through subsistence farming. Protection and connection with the forest is deeply rooted within many of their cultures, and indigenous Amazonian communities have been vital in conserving the areas. A study showed that indigenous lands had significantly lower rates of deforestation than non-protected areas (Sze, J.S., Carrasco, L.R., Childs, D. et al.). Native Amazonian tribes also use foods and medicinal herbs from the rainforest, using over 300 plant species and around 1,300 medicinal plants, all of which come from the Amazon rainforest (Shanley, 2011). These symbiotic connections between the rainforest and indigenous people are important for the wellbeing of both parties, helping sustain the life of both.

The Amazon is filled with huge, meandering rivers. The Amazon river has over 1,000 tributaries, several of which are over 1,500km in length (Sterling, 1979). There are around 412 dams operating along these rivers, which allow for hydroelectric power to be utilised by the countries which have regions in the forest. 80% of domestic energy production in Brazil comes from hydropower plants along Amazon rivers, resulting in it being one of the countries with the cleanest energy mix (International Energy Agency [IEA], 2023). The nine countries that own territories in the Amazon have the ability to become pioneers in renewable electricity generation.

On a global scale, the Amazon rainforest provides many resources that people use daily. Chocolate, avocados, moisturiser, medicine, coffee, nuts and vanilla are all products that commonly come from the Amazon. 10% of the whole globe’s biodiversity is found within the Amazon. The study of these creatures has led to pivotal discoveries. Through the study of Brazilian venomous vipers, scientists found ACE inhibitors which could treat high blood pressure, creating captopril and shaping modern medicine (Bryan, 2009). There are still vast sections of the Amazon that remain undiscovered. The advancements society could make through discoveries in these regions could change the world, displaying the importance this ecosystem holds.

It’s clear that the world would dramatically change without these ecosystems. There are so many reasons why they both play vital roles in regulating the globe and aiding human populations. They are also both interdependent: one could not exist without the other. They both regulate global climate and therefore, each other. I would like to challenge the question and argue that there is no way to preserve only one. The loss of one of these ecosystems would result in the degradation of the other. As discussed, sea level rise would result in deforestation and flooding of the Amazon, and deforestation in the Amazon would lead to increased CO2 emissions, causing melting of Antarctic ice. There is no binary decision that can be made when aiming to preserve ecosystems as large as Antarctica and the Amazon. In order to preserve one, you must preserve the other.