When you hear the term “pseudoscience” your mind may instinctively go towards the fields of study linked to acupuncture, aromatherapy, and other alternative types of medicine. And in this thinking, you would be correct. However, there is a whole segment of pseudoscience surrounding the study of psychology. Some of these sciences include phrenology, craniology, and the Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator personality test. These studies and practices have had major ripple effects on the way the brain is studied and how a person views themselves today.

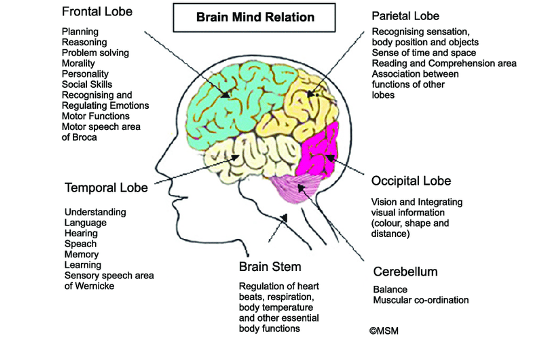

The pseudoscience of phrenology was developed by Franz Joseph Gall, a German physiologist, in 1796. He claimed that personality characteristics such as “benevolence”, “cautiousness” or even the capacity to produce children could be assessed by measuring the relevant part of a person’s skull. This theory attempted to prove that different sized bumps on the skull reflected the different sizes of the many different “organs” within the brain. These findings consistently proved that the more superior “organs” (parts that control intellect, impulsivity, rationality) appeared with larger bumps on men’s heads and were therefore larger and more powerful. Thankfully, the notion of phrenology fell into disrepute by the middle of the nineteenth century because of the unreliability of the skull measurements and lack of systematic testing. However, we still see some of the leading theories within modern neuropsychology particularly relating to the concept of cortical localization (Paul Broca, 1860), an idea that suggested that certain mental functions were localized in particular areas of the brain. While Gall and other phrenologists were incorrect about the importance of the lumps and bumps on the skull, they did inspire modern research methods which allow scientists to use sophisticated tools such as MRI and PET scans to learn more about the localization of functions within the brain. This knowledge can be used to treat, predict, and diagnose brain tumours or brain bleeds. Doctors know which areas of the brain control things like movement, behaviour and speech and the loss of these functions can indicate where the affected area may reside.

An important associate of phrenology was the pseudoscientific research of craniology, the study of skull measurements. The main studies would include measuring varied angles on the skull (height ratio, forehead) but the most popular, or the most likely to produce the “right” answer (that white males were “more intelligent and socially superior”), was the measurement of facial angles. Through these measurements it was concluded by a German anatomist Alexander Ecker, that women followed the facial characteristics of children and were therefore “infantile and inferior”. Racial craniology led to shocking discrimination on now what appeared to be “scientific” grounds. Georges Vacher de Lapouge, a prominent French anthropologist, was particularly in favour of such racialism. He created a hierarchy of humanity, hoping to instil a fixed social order. These conclusions and attempted hierarchy led to a deep-rooted movement towards conducting experiments to find the desired answer that would enforce the patriarchy and racist ideas, with eugenics adopted by the Nazi party for ideology and their race laws. Modern scientists are rightly addressing the horrors of what was done in the name of ‘science’. On a more positive note, craniology is used today in forensic investigations to determine the sex and race of deceased people when only skeletons remain. This can help solve a crime, determine the fate of a missing person, or enhance our historical knowledge surrounding a certain event.

In more recent times the phenomenon of personality tests through the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myer, 1917) has taken the world by storm. The test attempts to assign four categories: introversion or extraversion, sensing or intuition, thinking or feeling, and judging, or perceiving. It takes one letter from each category to produce a four-letter test result, such as “INFJ” or “ENTP” (Very Well Mind). These tests are regarded as pseudoscience because there are questions surrounding its validity, reliability, and how comprehensive it is of all parts of somebody’s personality. Also, it relies heavily on the Barnum effect which regards the “phenomenon that occurs when individuals believe that personality descriptions apply specifically to them (more so than to other people), despite the fact that the description is actually filled with information that applies to everyone” (Britannica definition). The results produced by these tests can influence the way people interact with the world and who they interact with. Although this type of pseudoscience does not present any dangerous issues it is interesting to think how gullible the human mind is and how much it craves understanding of itself. It can be damaging to compare a supposedly “scientific” test that tells you who you are and what you know about yourself. There are many websites that claim to tell a person who they should date or be friends with based on whether their personality tests are “compatible”. These types of conclusions can lead people to be narrow minded about their social circles and which opportunities they agree to or, on the other end of the scale, be overly trusting of someone who is supposedly “compatible” with them because of the personality test. Therefore, it has become important for the consumer to take any seemingly accurate result from a personality test with a grain of salt and continue to trust intuition over pseudoscience, which can be harder for some than others.

Overall, historic pseudoscientific psychology was used to elevate men and prove that women were inferior until they were largely discredited because of lack of validity. Nowadays elements of these theories are used to help fight crime, diagnose issues within the brain and they give a reason to make sure experiments are carried out fairly and without bias. Current pseudoscience in the form of personality tests is showing the world how easily influenced the human brain is, which could open even more doors of research. For these reasons, it is important to not completely ignore the pseudoscientific studies of the past or present because they may have elements of truth or logical thinking within them.

Credit: Research Gate

This article was inspired by the book “The Gendered Brain” by Gina Rippon, in which arguments have been especially used regarding Craniology and Phrenology.