What do John Coltrane, G.F. Handel, and Pyotr Tchaikovsky have in common? Apart from the obvious topic of music, they all integrated improvisatory techniques into their works. You may not think it, but improvising musically has been in use since the 10th century.

So how do we define musical improvisation? In the Western world, many think that the phrase ‘musically improvised’ can only be used in a jazz context, where you ‘create a melody’. However, to improvise on an instrument generally combines the skills of communicating through emotions and musical technique as well as responding concisely and spontaneously to other musicians.

Although plainchant and continuo in Baroque music may not have necessarily melodically influenced the jazz and ragtime of Charlie Parker or Miles Davis, the characteristics of a clear structure and use of improvising in both styles brings Baroque and Jazz are close enough to be comparable. Throughout the history of music up to the 20th century, these are the biggest and most common examples of musical improvisation:

Realisations and figured bass:

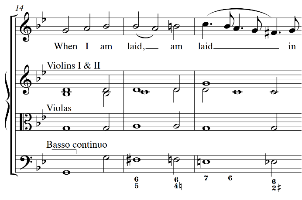

The origins of figured bass and realisations emerged from the late Renaissance practice of improvising harmonies over a bass line. The term ‘basso continuo’ was coined at the beginning of the 17th century by Lodovico Viadana, and was enough information to provide just enough information for an accompanist: like jazz, the accompanist is given the basic outline of a harmony through a bassline, as well as the chords they should play, shown through numbers of ‘figured bass’ that determine the harmony. This can be seen in the example shown: if an accompanist were on a harpsichord, then they would be able to understand the chord progression and inversion through the figured bass (numbers such as 6/5, 7 and 6 seen here) underneath the bassline. Thus, this allows an accompanist, usually the harpsichordist, to ‘realise’ a new line of melody alongside the original. Shown in the extract of music is Henry Purcell’s ‘When I am laid in earth’ from his opera Dido and Aeneas, and you can see the violins and violas building the harmony based off the figured bass in the basso continuo line.

Cadenzas:

One type of piece in classical music that has been written for many types of instruments throughout the Baroque, Classical and Romantic eras is the concerto. Since the beginning of concertos, cadenzas have been an underlying characteristic in the solo sections of the piece, hinting at the climax of the movement. The cadenza is usually a very virtuosic and technical part of the solo, usually unaccompanied and uses snippets of the original theme in the piece. The extract on the left is a snippet of the cadenza played in the first movement of PI Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto – this is a typical example of a cadenza due to the variety of technical skills needed to play it. However, while cadenzas used to be more ‘up to the soloist’s discretion’ and not musically notated, cadenzas are now usually written out by either a well-recognised performer or the composer themselves, so while cadenzas may not be strictly improvised on the spot, the overall improvisatory feel of the cadenza will always be there.

Jazz improvisation:

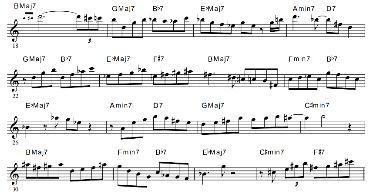

This is single-handedly the biggest example of musical improvisation used in any genre: classic jazz is built off improvising and ‘soloing’ on top of the chords of the main melody. Of course, the style and the length of your improvisation will depend entirely on what subgenre of jazz are you playing, and if there are backings to your solo (if the other instruments in your band give you an accompaniment of fragments of the head). One misconception about soloing in jazz music is that it must be very dense and very virtuosic every single second of the solo: this is not true at all. Yes, some soloists play very intensely and very technically (such as John Coltrane’s solo in Giant Steps seen here), but there are also very famous jazz musicians such as Miles Davis that are slower and calmer in their improvisation.