Colonialism is often perceived as a relic of the past, disconnected with the actions and policies of governments today. Likewise, modern day conflicts are regularly viewed through a vacuum, with little understanding of the historical background behind them. However, to understand the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine, one must look at historical events that altered the borders of the regions — The British Mandate, the UN partition of Palestine and 1948 Arab Israeli war that followed, and the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. The struggles over land, sovereignty, and a representation of identity are results of several border changes in the region throughout the past century. Borders provide a vital sense of clarity and security in an uncertain world and are thus powerful tools. However, when borders fail to reflect the interests of a group of people, they can become a site of resistance and conflict, underscoring the limitations of borders in fully encapsulating the complexities of nationhood and self-determination.

The British Mandate:

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, in 1922, Britain was granted a Mandate for Palestine. For the first time in centuries, Palestine’s borders were formally defined, but its newly drawn borders reflected imperial priorities rather than the aspirations of the region’s inhabitants. As part of the Mandate, Britain assumed a “dual responsibility” to both Arab and Jewish populations, which it sought to balance through the incorporation of the Balfour Declaration. By 1917, many Palestinians had already begun to view the Zionist movement, founded by Theodor Herzl, as a potential threat to their national sovereignty. However, the Balfour Declaration introduced a new dimension to their concerns. The statement pledged support for the establishment of a ‘national home for the Jewish people’ in Palestine, and committed to ‘facilitate the achievement’ of this. Behind the façade of diplomacy, the Declaration was problematic, as it dismissed the Arab majority— approximately 94% of the population—as the “non-Jewish communities”, reducing them to a marginal note in their own homeland. Moreover, the Balfour Declaration fundamentally contradicted the Hussein-McMahon correspondence: a series of letters exchanged between the Emir of Mecca and the British High Commissioner of Egypt outlining a deal in which Britain offered support for an independent Arab state in exchange for Arab cooperation in opposing the Ottoman Empire. Thus, two incompatible visions for the region were on the table. The British solution to this was the separation of the British Mandate for Palestine into two separate entities: Western Palestine, reserved for the Jewish State, and Transjordan, where Jewish settlement was prohibited. This division was not guided by the needs or wishes of the local population but rather by Britain’s desire to manage competing Zionist and Arab demands whilst securing its strategic interests in the Middle East. This demonstrates how imperial convenience in a nation is often prioritised over the aspirations of the people living within those borders. Notwithstanding the attempts to appease both groups, this decision laid the groundwork for deep division between the Arabs and the Jews. On one hand, Palestinian Arabs saw this partition as typical colonial manipulation, intensifying their territorial claims and resentment for the Zionist project. On the other hand, Zionist leaders focused on increasing Jewish immigration and settlement in Western Palestine. Undoubtedly, the imposed borders escalated tensions greatly and highlights the extent to which colonial powers used borders as tools of control, often with little consideration for the enduring human consequences.

The UN Partition Plan:

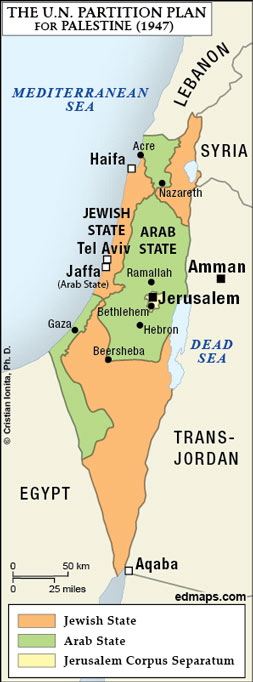

In the face of the threat of complete annihilation due to the Nazi extermination of Jews in Europe, the idea of partitioning Palestine, once more, began to gain traction. Zionist leaders considered: where were the displaced survivors of the Holocaust to go? This was an issue that was widely recognised by international governments, and subsequently, the UN General Assembly Resolution 181, recommending the partition of Palestine into two independent states, was passed on November 29, 1947. The plan stated that approximately 56% of the land would be allocated to the Jewish state and 43% to the Arab state, despite Jews comprising only about one-third of the population at the time. This decision was made under the assumption that the Jewish population would grow rapidly as a result of immigration. The Jewish state was to include two thirds of the coastal plains, where Tel-Aviv is situated, much of the fertile North, and the Negev Desert. The Arab state would comprise of Western Galilee, including Nazareth, the central Palestinian highlands encompassing the cities of Hebron and Ramallah, and one third of the coastline, where Gaza lies. Jerusalem and Bethlehem were to be placed under international administration due to their religious significance to both Muslims and Jews. What was once a single, unified entity under the British Mandate was now divided along ethnic and religious lines, sowing the seeds for future division. For the Jewish population, the plan represented a historic opportunity to achieve statehood after decades of Zionist activism and increasing Jewish immigration. On the contrary, the Palestinians viewed the partition as unjust, and, in their eyes, allocated a disproportionate amount of land to the Jewish state and disregarded their fear of Zionist settlement. The proposed borders fragmented Palestine into small, disconnected areas, which made the idea of a viable Palestinian state increasingly difficult. By ignoring the deep historical, cultural, and religious ties that Palestinians had to their land, particularly the holy city of Jerusalem, and failing to involve Palestinians in the decisions over their own borders, the feeling of injustice was intensified. The establishment of these geopolitical borders reveals the limitations of such boundaries in satisfying two groups of people. Whilst they can create new opportunities for identity and statehood, it is often at the cost of marginalising others.

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War:

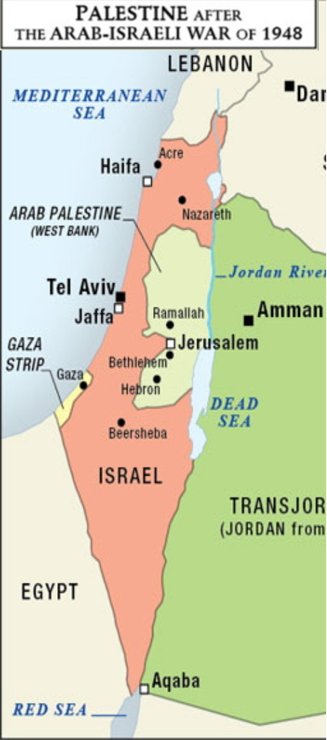

The Arab-Israeli war of 1948, originally contained to a Civil War between the Palestinians and Israelis, escalated into a wider war when Israel declared Independence, prompting the Egyptian, Transjordanian, Syrian, Lebanese, and Iraqi armies to join Palestinian forces in invading Israel. The war lasted for less than a year, officially ending with an Israeli victory, but the new borders were to remain for much longer. Under the Green Line, Israel gained control over 78% of historic Palestine, far beyond the partition’s allocation. Over 700,000 Palestinians were expelled or forced to flee by the Israeli military, resulting in a refugee crisis that persists to this day and a profound demographic shift. For Israelis, however, an even stronger national identity was fostered as it was tied to the physical boundaries of a state. Again, this highlights the fact that borders implemented for the safety of one group can have the opposite effect for another. Yet even for Israel, these borders remained contested and insecure. The Egyptian–Israeli General Armistice Agreement, for example, stated that “the Armistice Demarcation Line is not to be construed in any sense as a political or territorial boundary”. This statement emphasised that the Green Line was purely a military boundary, not a permanent border, and its purpose was to maintain peace in the region. Despite this, the Green Line was often treated as a permanent border due to the lack of concrete peace agreements. Furthermore, Israel fully integrated its territory by applying its legal framework, governance, and infrastructure, granting citizenship to residents and creating a unified economic system. This arguably made the quality of life for Israelis much higher than for Palestinians, who lived under military occupation by Jordan and Egypt. Additionally, Israeli courts and laws operated exclusively within the Green Line, distinguishing it from the areas beyond, where separate Jordanian and Egyptian legal systems prevailed. To this day, Israelis can cross the Green Line freely, whilst Palestinians cannot, with those who live in the West Bank facing strict Israeli controls at checkpoints and movement between Gaza and the Green Line being extremely limited due to an Israeli blockade. This stark contrast highlights that the experience of borders is not universal; the very same line can have vastly different effects for different people. It is clear that the borders implemented were used by powerful governments, particularly Israel, but also Jordan and Egypt, to advance their ambitions in the region, proving that borders do not always reflect the people living within them but rather the governments controlling them.

The 1967 Arab-Israeli War:

In 1967, tensions between Israel and the Arab States of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan escalated into war, triggered by Israel’s initiation of Operation Focus, a coordinated aerial attack on Egypt. This was in response to intelligence and rumours suggesting that Arab forces were mobilising at the borders. The war lasted for just six days, but similarly to the 1948 War, the geopolitical landscape of the region was significantly altered with the seizure of the remaining Palestinian territories — the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, as well as the Syrian Golan Heights and the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula. Whilst these borders remain unrecognised by the UN, the war’s aftermath was a watershed in the development of the Zionist project and the escalation of Palestinian oppression. This war shows us two things: the way in which borders are used as a means of control, and the importance of borders in shaping national identity, both Palestinian and Israeli. Palestinians in the captured lands were forced to live under strict Israeli control, and since the administration of these territories was set up to put Israeli interests first, Palestinians were left without a place to live freely. Perhaps the most significant indicator of this was the start of Israeli settlement programs, particularly in the West Bank, and the significant displacement of Palestinian communities that followed. The settlements deepened the fractures of the Palestinian State, making it extremely difficult for Palestinians to establish a cohesive society and viable government. Furthermore, these settlements were often built on land Palestinians needed for agricultural and urban developmental purposes, severely hindering economic progress. In regards to national identity, the loss of the remaining land meant that the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), formed in 1964, became much more active. Palestinians sought a centralised force to truly represent their aims and advocate for their rights, and the PLO became a unifying symbol of Palestinian identity. For Israelis, the idea of a ‘Greater Israel’, the Jewish ‘historic Biblical land’, was realised through the occupation of the West Bank. Territorial expansion was therefore seen as justified, fuelling a sense of national pride. This illustrates how the gaining of land can strengthen nationalist ideas, but the loss of land can also catalyse a movement to become stronger and more unified than ever in the face of such adversity.

Conclusion:

In light of all this, several conclusions can be drawn regarding the extent to which geopolitical borders define us. Firstly, borders are drawn by the few, but impact the many, and the few are often far removed from the profound consequences of their decisions. Second, borders are not experienced universally, in fact they often have completely contrasting effects on different groups living within in a territory. Additionally, borders are used as a way of fuelling ideology and exerting control. They enable governments to exploit and dominate, resulting in deep inequality. To this extent, borders define millions of people’s lives, rights, and freedoms, and dictate the success of political movements. However, borders also have limitations. Despite the efforts to divide communities, borders can inspire a resistance movement, leading to a seemingly endless cycle of violence. Evidently, borders transcend lines on a map; the profound implications for the people they separate and the states they define attempt to reshape national identities, and fuel conflict for political goals.