Masculinity is more common than mud in the working world. Not only are nearly 90% of CEOs and executive directors men, but women with ‘masculine’ traits and styles of work have been proven more likely to succeed in an environment otherwise dominated by men. Margaret Thatcher, for example, had professional voice coaching to lower her voice to a more ‘masculine’ level in order to seem more authoritative and respectable. This logic, unfortunately, carries through to work attire. The most common outfit worn by women in corporate environments usually involves a shirt and blazer, traditionally paired with a skirt, heels and makeup. While the latter components are becoming rarer as forcing traditional and inconvenient ‘femininity’ onto women is becoming less accepted, the classic collared blouse and jacket combination shows no sign of decline.

It is no coincidence that these two items both originated in men’s clothing, and still bear a large resemblance to the typical suit donned by businessmen globally. In fact, when Professor Sandra M. Forsythe of Auburn University conducted a study on the effects of ‘masculine’ clothing on the hiring of prospective job applicants, she found that the more masculine the outfit, the more likely the applicant would be hired – regardless of the gender of the person making the recommendation. Additionally, applicants in more ‘masculine’ clothing were perceived as having traits that predict success in climbing the corporate ladder.

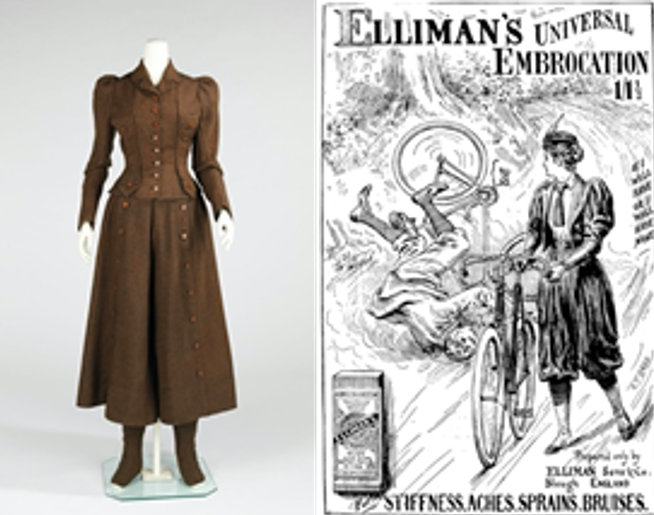

But where do these ideas and conventions come from? Well, throughout history, it has been a recurring theme that whenever women have participated in activities traditionally dominated by men, the clothing they wore to do so has emulated men’s styles. For example, between the mid 17th-19th centuries, women usually wore a set of garments called a ‘riding habit’ when riding on horseback (regarded as a very masculine activity). This outfit tended to consist of a tailored coat, shirt, long skirt, and a hat that often mimicked the most formal men’s style of the era. Skirt aside, most riding habits looked remarkably similar to men’s riding styles – to the extent that some women, such as Anne Lister (1791-1840), wore habits even when not riding to deliberately appear masculine.

Riding habits are not the only example of this trend. The emergence of walking or traveling ‘costumes’ in the early 19th century also took heavy inspiration from day-to-day menswear of the era. Much like riding, these outfits were worn for things traditionally ‘unfeminine’ (i.e., making your own way in the world), and reflected the growing independence of women in the contemporary society. Around the same time, sport started to grow in popularity as a leisure activity for women. Sports such as archery, tennis and cycling were previously very considered ‘men’s sports’. Thus, the clothes women wore for these activities were based on the typical menswear for them. This included ‘bloomers/knickerbockers’ and ‘split skirts/cycling skirts’- essentially trousers.

The legacy of these trends and choices is still present today – namely in the fact that traditionally ‘male’ garments are still donned without thought in traditionally male -dominated environments, almost like a camouflage. This perpetuates the harmful bias that femininity equates performing less well in a corporate environment, upholding and reaffirming patriarchal inequalities. This article is not a condemnation of the shirt/blazer combo – on the contrary, I am a massive advocate for women in suits in any context. That said, I urge you to examine the reasons behind your subconscious fashion choices, and be aware of the patriarchal conventions they uphold, and at least use those conventions to your advantage.