The destruction of art is as much a part of art history as its creation. From the Roman times to the present-day, people have felt the need to destroy it, often justified by religion, politics, power, and morality. The toppling of statues, the erasure of portraits or the destruction of images reveal what it is that people value in art and why it matters enough to be worth attacking.

An historical ideological debate about images that led to their widespread destruction was the Iconoclastic Controversy between 726 – 843 CE in the Byzantine Empire. At this time the Byzantine Empire was an expansion of the Roman Empire into the east with Constantinople (modern day Istanbul) acting as its capital. The core of the debate was over images of God and figures in Christianity, with iconoclasts arguing they would anger God due to their potential to be misused as idols. The ‘Quarrel of the Images’ became a violent argument and later a civil war which would ebb and flow throughout different rulers who each had varying stances. . Icons were, and are still, used as a way to enable you to communicate with the divine. The idea was you would say a prayer which could pass through the image to go directly to the figure represented. Icons were also valued as a way to connect the illiterate with religion and God. Pope Gregory the Great in a letter stated:

“To adore images is one thing; to teach with their help what should be adored is another. What scripture is to the educated, images are to the ignorant; who see through them what they must accept; they read in them what they cannot read in books”.

Icons were another way to tell the story of God. However, others argued that it was a violation of the Second Commandment: ‘You shall not make yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the Lord your God am a jealous God’. With the exception of brief periods when two women with iconodule policies ruled Byzantium, images were destroyed in vast numbers with paintings and mosaics whitewashed, while others were chiselled away with new, approved iconography like crosses, inserted.

The process of destroying art can also be seen as a way of asserting power. In the ancient world of Mesopotamia, Greece, Egypt and Rome, the process of damnatio memoriae, meaning ‘condemnation of memory’, was used. In ancient Rome the practice was a way to condemn Roman elites and emperors after their deaths. If the senate or following emperor did not like the acts of the individual, they could have his property seized, his name erased, his statues reworked, and his portraits defaced. One notable example is that of Emperor Geta who was murdered by his brother Caracalla. The new emperor ordered damnatio memoriae which led to the erasure of Geta throughout the Roman Empire. This removal can be seen in the Tondo of Septimius Severus, Julia Domna, Caracalla and Geta. Geta’s face clearly has been purposely erased but the very visible way in which it has been done conveys a very strong message. Caracalla wants people to know that he had the power to erase him, he’s saying ‘remember to forget Geta, remember I had the power to do so’.

The severity of the punishment and the assertion of power is further emphasised by the fact that the image of an emperor was just as important as the emperor himself, especially in an empire of its size. Images became stand-ins for him: ‘For the likeness of the emperor in the image is exact… to one who after viewing the image wished to view the emperor, the image might say: “I and the emperor are one; for what you see in me you behold in him, and what you have seen in him, that you behold in me’ Accordingly he who worships the image also worships the emperor in it, for the image is his form and appearance”. Like icons the image was another way of connecting to the person depicted and a way of legitimising power. The value placed upon these images made its destruction that much more significant.

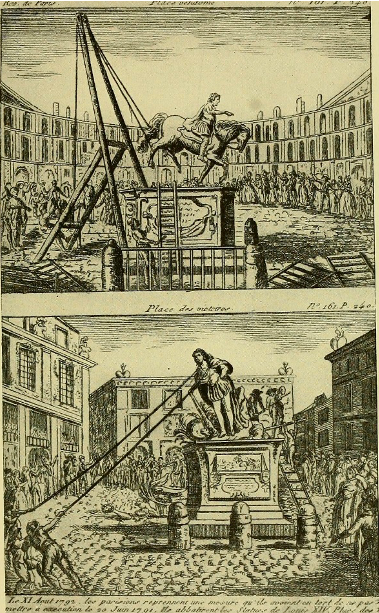

Maybe one of the most intense and frenzied periods of iconoclasm was during the French Revolution where the old order was destroyed to make room for a new nation. The value placed on art in France pre-revolution made the process divisive, mostly among academics. Art was valued as an important part of their heritage and culture, with it being utilised as a tool for both the illiterate and the literate. However, many saw the paintings, sculptures, and architecture as a representation of everything they were trying to remove. Like the monarchy, the magnificence of the art was seen as an insult to the poverty of the people and to ‘the simplicity of republican morals.’ The ‘emblems of feudalism’ and ‘spoils of prejudice and arrogance’ were everywhere and resulted in frenzied crowds destroying and taking down everything within their reach. Statues of kings, paintings in churches and buildings themselves were torn down, with items often being thrown onto bonfires. Iconoclasm played an important role in the Revolutionary process – to foster it, to incite conviction or fear and to make the change appear and become irreversible. There were some attempts to preserve the art by the Monuments Commission but were undermined by new legislation that required all symbols of the Ancien Regime to be destroyed within eight days, upon pain of confiscation of the property where such symbols still existed. It is because images are used to express, impose and legitimize power that the same images are destroyed in order to challenge, reject and delegitimize it.

Throughout history, people have been destroying art because it has inherent meaning and value. In the Byzantine and Roman era, and in the French Revolution, art and images, especially those of leaders, have been used as ways of connecting the people to a person and a way of legitimising their power. In destroying it, the iconoclasts are rejecting that authority and asserting their own.