… is quantitative easing (QE). Okay granted, quantitative easing is not officially a secret – but most of you may not have heard of it before. Despite this, QE is a hot topic in the world of monetary policy. It is both fascinating and controversial. To fully explain and evaluate this ‘quantitative easing’, we must first understand the UK’s economy a little.

The core principle that underpins most modern economies is the existence of a reasonable level of aggregate demand (AD). It incentivises firms to invest, which through the multiplier ultimately incentivises consumers to spend; a nice self-fulfilling economic cycle. One way in which governments can keep this demand high is to encourage spending and lowering interest rates is their main tool in doing so. This method is effective as by lowering interest rates, both consumption and borrowing are more highly incentivised, both of which are key factors for increasing aggregate demand. But how does this connect to quantitative easing? Well, there exists a problem with interest rates: there’s a limit to how low they can go. When all else fails, governments have been known to use QE instead to stimulate demand in the economy.

Here’s how this works: central banks increase the money supply by introducing new, digital money that is used to buy bonds from financial institutions, like other banks, pension funds and the government. Now, these financial institutions have more cash, having sold their bonds to the government. Subsequently, there is more liquidity in the financial sector, ergo, these institutions can lend more to firms/consumers. With this money, resulting from this higher credit level in the economy, firms can therefore invest more whilst consumers can buy more. A higher level of demand has been achieved; consequently, so has a higher level of economic growth.

Not only does this lead to a higher level of credit and liquidity in the financial sector, but QE also impacts the price of other bonds. Large scale government spending on bonds creates higher demand, meaning their prices rise (ceteris paribus). Consequently, the yield on said bonds falls; returns have fallen in comparison to the price. The yields of other bonds in the bond market (there are many different types of bonds) fall in tandem, as are connected through the bond market. So, we see that QE has the effect of lowering the yield curve on bonds, meaning investors are more likely to invest in the real economy where better returns are to be found – providing a cheeky economic boost.

Why and when was it introduced?

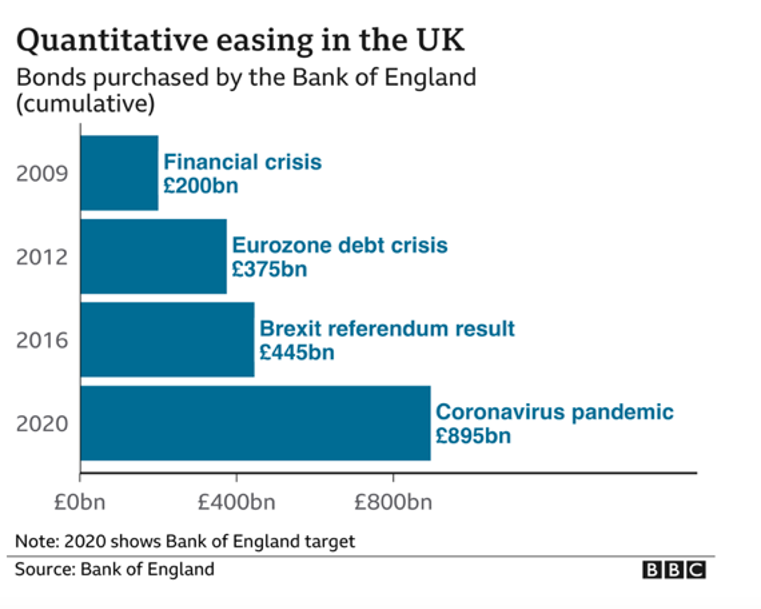

QE was introduced in 2009, when the UK economy was suffering terribly from the Financial Crash that had occurred in 2008. Whilst interest rates at the time were a mere 0.5%, demand was still very low, therefore the Bank of England (BOE) used this unconventional tool to try and remedy that. Mark Carney, governor of the BOE at the time has estimated that £200bn of quantitative easing is equivalent to lowering interest rates by 1%. In monetary policy, that’s a big deal. Ever since then, QE has been maintained in the UK economy, with further rounds being enacted at points of crises.

Graph to show rounds of QE in the UK. Note that the figures are cumulative. Source – Bank of England

But the question remains as to whether QE has adequately achieved its aims. Have there been unforeseen consequences of this large scale buying of bonds? Has this been a generally positive step for the UK and its economy?

The impacts of quantitative easing

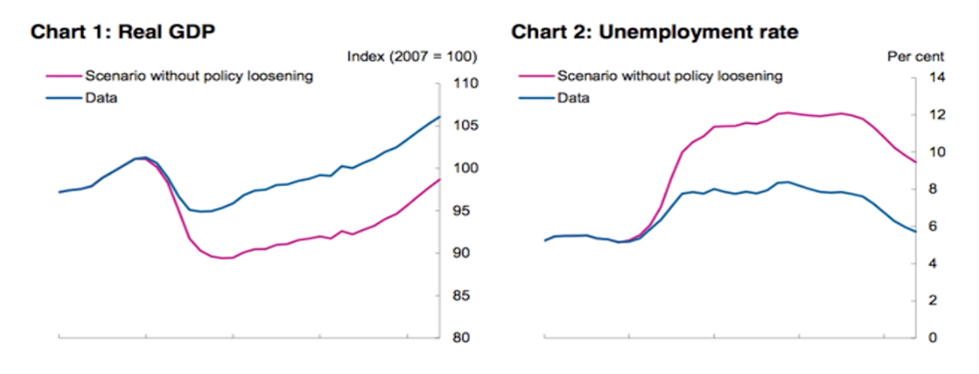

A key objective of the first round of quantitative easing (let’s call this QE1), was to mitigate the impacts of the 2008 Financial Crisis. Though we can never know what would have happened without QE1, analysis does suggest we managed to avoid the worst of the crisis. Unemployment peaked at 8.5%, compared to 10% in the US and 12.1% in eurozone following the crisis. The UK enjoyed a jobs-rich recovery post-crash and had the longest unbroken quarterly growth streak of any G7 nation.

Graphs to show the impact of QE1 on the UK’s economy post 2008 Financial Crash – comparing hypothetical data without QE1 with real data. Source – Office for National Statistics

Most research does suggest that the UK economy was protected from the Financial Crash due to QE1. As David Blanchflower, one of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) members who decided to enact QE1 says, “It was the equivalent of 10,000 Warren Buffets showing up. Two people saved the world. Bernanke saved the world on the monetary front and Gordon Brown on the fiscal front.”

On the flip side, though QE probably helped avert the Financial Crash’s impacts, its effectiveness has been somewhat stifled since. At the time, QE was thought of as a one-time, stand-alone monetary tool, only to be used in times of acute crisis. Whilst recent rounds of quantitative easing have been in response to crises, the eurozone crisis for example was arguably not as impactful on the UK economy. Not compared to the 2008 Financial Crash that is; after all, the UK is not part of the eurozone. It was certainly marketed as once-in-a-lifetime solution in 2009. Andrew Sentance, another economist who was on the MPC at the time states, “The real problem…is that [QE] hasn’t turned out to be an emergency measure, it’s turned out to be the status quo.” Not only has the BOE exhausted this extra tool of monetary policy, but now financial markets have learnt to anticipate QE, meaning it has lost its initial potency.

That being said, the additional credit in the financial system thanks to QE has helped firms greatly, even though this measure “has turned out to be the status quo”. Firms in the UK are now able to invest more, as banks have more cash due to quantitative easing. This is positive for the economy due to a number of reasons. It helps UK businesses expand and increases the UK’s global reach. Employment too is likely to rise if firms invest more; they will need more workers. However, there exists widespread criticism that QE has led to wealth inequality in the UK.

It’s hard to quantify whether wealth inequality would be lower without quantitative easing; though there is evidence suggesting that QE does cause inequality, the economic downturn it helps to mitigate certainly leads to wealth inequality too. But nonetheless, let’s look at a component of inequality that has most likely been furthered by QE: the inequality between homeowners and non-homeowners.

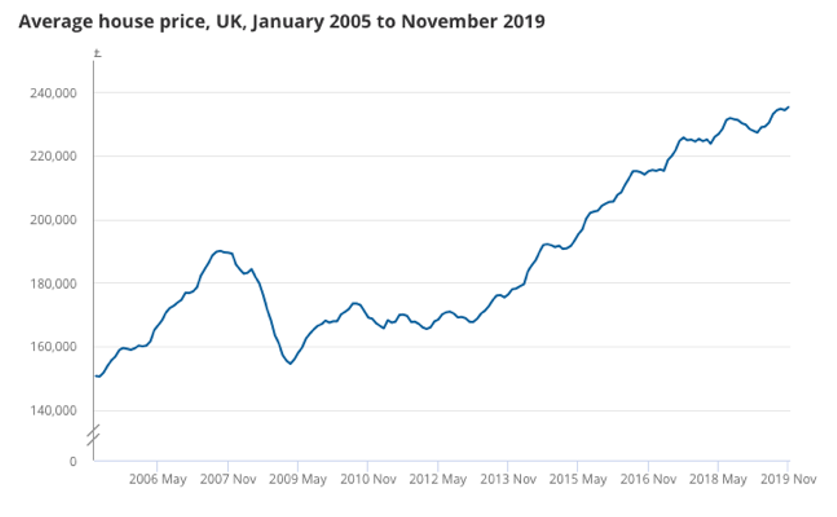

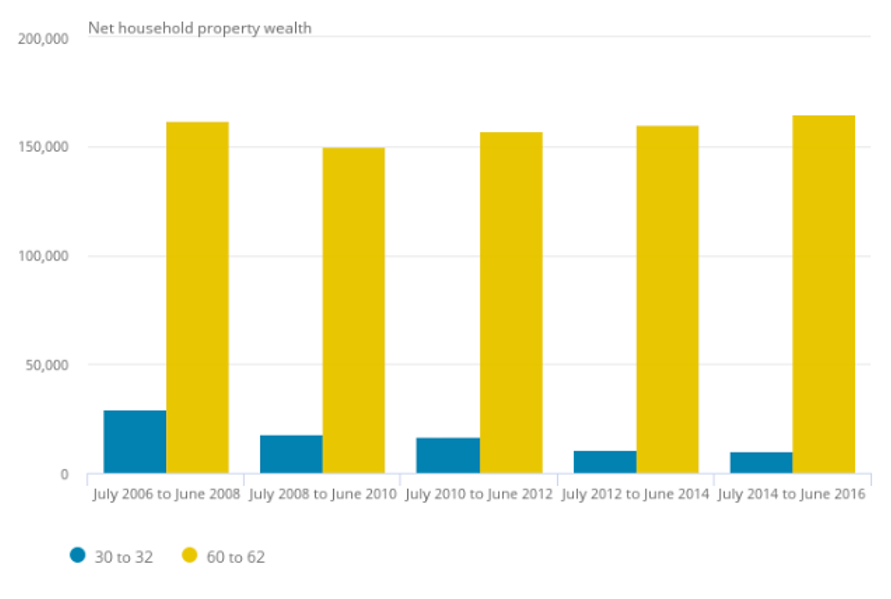

Just as QE lowers interest rates in the bond market, it does too in the wider economy; lower interest paid on deposits means consumers look elsewhere for better returns. Investors may move from the bond market to another market, for example the stock or housing market, if interest rates are too low on the bond one. In effect, this is how QE increases asset prices; stimulating demand in other markets. But how does this increase wealth inequality? Well, homeowners and those with significant investments in the stock market tend to already be wealthier and older; hence the rich get richer whilst the poor remain so. A higher level of saving becomes necessary for prospective homeowners, which also applies downwards pressure on the UK economy. In addition, older people tend to spend less in the economy than younger people, increasing wealth inequality in the UK whilst possibly hindering economic growth too.

Graph to show average UK house prices from January 2005 to November 2019. Source – Office for National Statistics

Wealth inequality can threaten social cohesion and raise crime levels, but most importantly for the question I’m seeking to answer, can lead to a two-speed economy; the top percentile getting richer and richer whilst the poorest remain stuck under the poverty line. Indeed, Britain is ranked the fifth most unequal country in Europe and there is a six-fold difference between the income of the top 20% and the lowest 20%. 44% of the UK’s wealth is owned by just 10% of the population. However, we can’t ignore the fact that QE leads to increased levels of employment, boosting the wealth of the worst-off in the country. Quantitative easing also makes it easier to borrow as stated earlier, again, benefitting those struggling to make it from month to month.

Graph to show the difference in net household property wealth of 30–32-year-olds, compared to 60–62-year-olds. Source – Office for National Statistics

There is no sure-fire way to decide definitively whether quantitative easing has had an overall positive effect on the UK’s economy. Hypothetical data analysing QE’s mitigation of the Financial Crash is just that: hypothetical. In many ways, quantitative easing has increased economic growth and created jobs. It is undoubtedly another nifty monetary tool that the BOE now has up its sleeve. Yet the wealth inequality that QE’s detractors blame it for causing does have some truth to it and it was always proposed as a one-time option. Nor have I even touched on the inflation that quantitative easing could play a part in. We can’t yet claim to know the extent of QE’s impacts on the UK; 12 years on is still too early to tell. I would say that the state-owned (though relatively independent) Bank of England owning such a large quantity of bonds could have possible repercussion in itself; here lies a more free-market argument. The question remains: would the UK’s economy be better off without quantitative easing? I’m not sure of the answer; you can decide this one for yourself.