In his address to the UN Security Council on 23rd February 2021, David Attenborough articulated the threat currently faced by humanity: “If we continue on our current path, we will face the collapse of everything that gives us our security…Climate change is the biggest threat to security that modern humans have ever faced.” According to Attenborough, food production, access to fresh water, habitable ambient temperature and ocean food chains are all at stake, the most basic of human needs. If ever humanity needed a weapon for changing the world, it is now. In the face of these challenges, it is difficult to conceive of a more powerful tool than education. It can leverage women’s concern for the environment, provide them with more life choices and develop technologies to plug the gaps left by an aging population. While education has a wealth of other benefits, mentioned are the central themes I will explore further in this essay, starting with the role of female education in driving the climate agenda.

Leveraging women’s concern for the environment

There is strong correlation between increased female political participation and the passing of environmentally orientated policies, with several studies demonstrating that greater female parliamentary representation results in countries adopting more stringent climate change policies (Mavisakalyan & Tarverdi, 2019). In Denmark, for example, a country with 37% female representation, climate change policies are around eight times as stringent as those of Bahrain, a country with 2% female parliamentarians. This concern for the environment is consistent with a study on attitudes more broadly. Namely, in America, a study of the general public in 2011, suggested females have a greater awareness and concern about climate change than males (McCright & Dunlap, 2011). According to Christina Kwauk, fellow at the Centre for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution, this is in part because women tend to be the key providers of care across society and therefore often have a higher perception of vulnerability and aversion to risk than men (Kwauk, 2020).

Furthermore, a study across nineteen OECD countries between 1960 and 2005 showed female politicians are more likely to address issues that affect women (Criado-Perez, 2019). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) showed the consequences of climate change are gender-differentiated: 80% of people displaced by climate change are women, who are more likely to suffer extreme poverty as a result of climate-related disasters (Habtezion, 2016). This goes some way to explaining why women care more about the environment than their male counterparts.

With female politicians more likely to drive environmentally focussed policies once in government, education can play a key role in increasing their numbers. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) found, as levels of female education rise, women’s political, social and economic representation expands (Goetz, 2003). American sociologists Burns, Schlozman and Verba assert that “education is an especially powerful predictor of political participation”. This is concordant with another study revealing that the higher the level of women’s formal education, the higher their tendency to participate in politics, both in voting participation in elections and occupation of political post (Dr Sahu & Yadav, 2018); clearly the planet benefits from increased levels of education too.

Providing women with more life choices

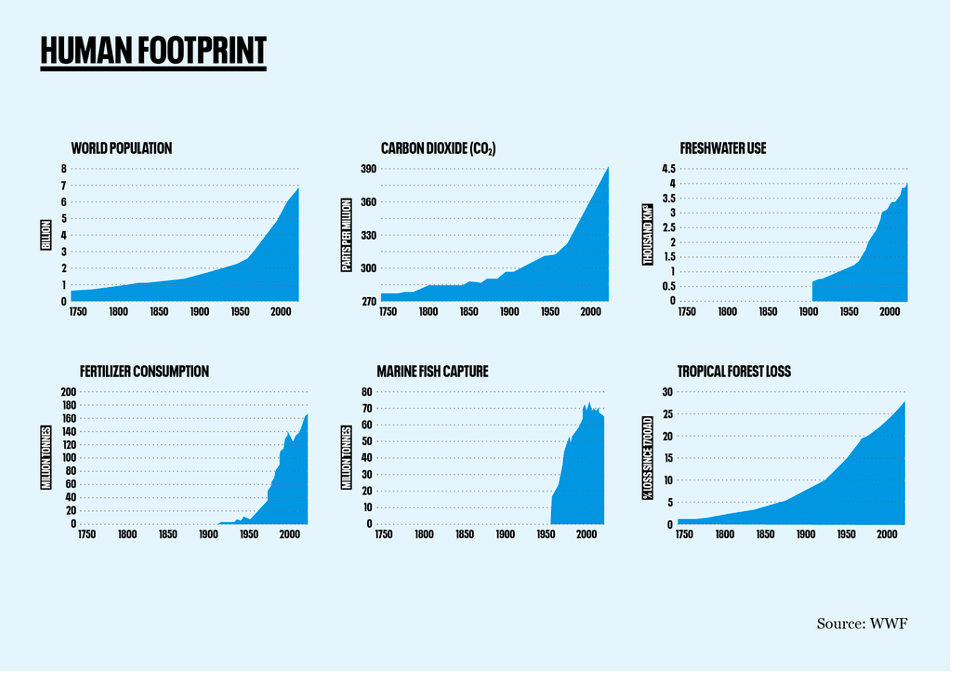

While increasing female political participation helps drive the climate agenda in politics, female education can play a much more impactful role in moving towards a sustainable future: slowing and, ultimately reversing, population growth. The environmental debate is currently focussed on shorter term, albeit necessary, strategies (for example, transitioning to a more plant-based diet and to renewable energy sources; and innovation in carbon capture technology). But, if the human population continues to grow, and many scientists argue even if it remains at its current level, it will consume more resources than Earth is able to provide. Evidence provided by the WWF shows humankind’s impact on key environmental measures (see Figure 1); only a reduction in population growth offers a long-term solution to the climate crisis.

However, politicians, female or otherwise, cannot demand people have fewer children: it is seen as a basic human right, driven by an evolutionary urge to procreate. A more viable and ethical alternative could be to facilitate greater individual choice through increasing levels of female education.

In some countries, particularly less developed countries, higher levels of female education can reduce fertility rates because:

- The older generations often rely on their children to provide care in later life. However, infant mortality rates can be very high and consequently women choose to have more children. With higher levels of education, women can provide better care for themselves, reducing the risk of infant mortality at childbirth (each extra year of schooling reduces the probability of infant mortality by 5-10% (UNESCO, 2011)), and better care for their children post-birth, driving higher infant survival rates (a child born to a mother who can read is 50% more likely to survive past the age of 5). When children are much more likely to survive to the time at which they provide care, the need to have more children is lessened.

- Families can be heavily dependent on children to provide a source of household income, but better education brings higher individual (parent) earnings (the UNESCO study showed one extra year of schooling increases an individual’s earnings by up to 10%). Higher levels of parental income lessen the need for income-generating children.

- Unintended pregnancies are minimised as focussed education raises awareness of family planning options and can debunk false perceptions about the side effects of contraception (Mahamed, et al., 2012).

Paul Hawken, founder of Project Drawdown, a major international study that ranks climate actions according to their effectiveness, says uneducated women (or girls taken out of school early) have an average of around five children, whereas girls who remain in education have an average of about two children (Hawken, 2020). This is consistent with a UNESCO study in Mali, showing women with secondary education or higher have an average of three children, whereas those with no education have an average of seven (UNESCO, 2011).

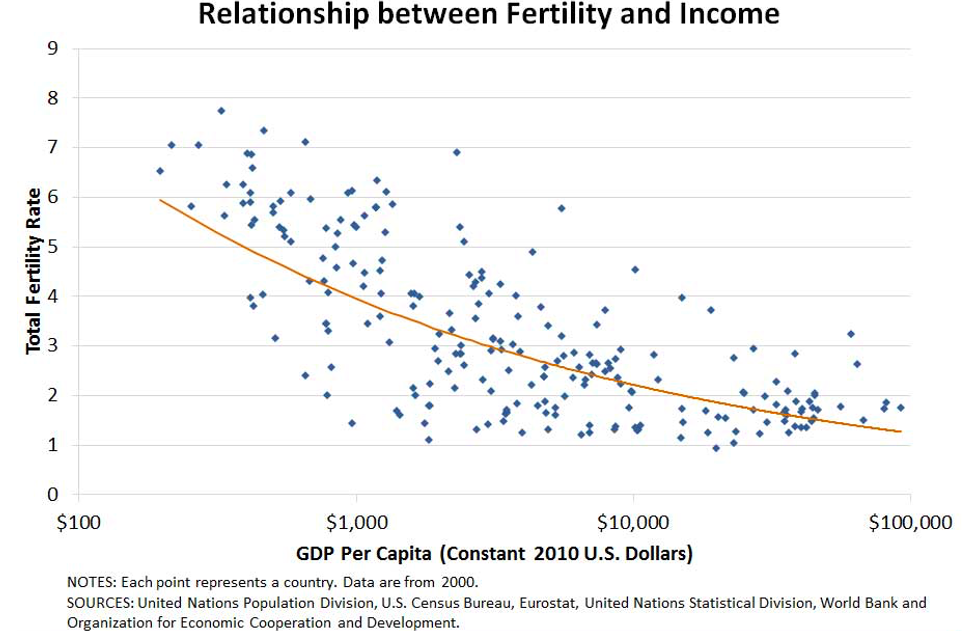

But the benefits of educating women are not just felt in developing countries: in all parts of the world, higher personal income, a product of higher educational attainment, results in a greater opportunity cost from having children – less income is earnt during the time spent on childcare – and as a result, women tend to choose to have fewer children. Figure 2 shows the strong negative correlation between income and fertility rates.

Project Drawdown predicts that in order to limit global warming to 2° by 2100, as set at the Paris Accord, combining increased levels of education of girls with increased access to family planning could reduce atmospheric CO2 levels by 85 billion tonnes by 2050 (Hawken, 2017), more than the combined potential benefits of offshore and onshore wind turbines.

Developing technologies to plug the gaps left by an aging population

Lowering fertility rates inadvertently increases the tax and social burden on the working population by the non-working, elderly population. Typically, state-funded benefits (e.g. pensions, healthcare, unemployment benefits) are primarily generated through the taxation of the workforce. Significantly slowing population growth inevitably increases a population’s average age (UN, 2017), reducing the relative size of the workforce, as retirees make up a higher proportion of the population. In Japan, the country with the fastest aging population (UN, 2019), the government is having to spend more on healthcare and public pensions alongside a shrinking workforce and, therefore, a shrinking tax base (Mühleisen & Faruqee, 2001) – a recipe for economic stagnation. This is where education, or training, not of people, but of Artificial Intelligence (AI), can compensate.

Machine learning is a branch of AI, that involves feeding large quantities of data into one of many algorithms which learn and detect patterns, and then applies these patterns to any new information it encounters (Pang, 2020). It is what allows a computer to tell the difference between a cat and a dog, diagnose cancer from an MRI scan and communicate effectively with human beings. By training algorithms, it is possible for AI to do many of the jobs that a smaller workforce would otherwise be unable to do (Schneider, et al., 2018). Consider a doctor whose workload is increasing due to the demands of an aging population; AI-powered software trained to diagnose common medical conditions (e.g. coronary heart disease, flu, diabetes) can work alongside her, allowing her to focus on more complex medical tasks. Consequently, one doctor can efficiently treat a much larger number of patients and so fewer will be required to meet the growing medical needs of an aging population.

Robots are already being deployed in care homes on an experimental basis, to support, for example, people with dementia. AI is trained in the interests and backgrounds of care home residents, and, via a human-form robot interface, provide much of the social interaction patients need, as well as offering reliable, practical help such as medicine reminders (Booth, 2020). In Japan it is predicted that there will be a shortage of one million caregivers by 2025 (Muoio, 2015); nurse-care robots are providing an alternative.

Generally, developed countries already have fertility rates below the level required for a population to exactly replace itself, which is roughly 2.1 live births per woman (Nargund, 2009). In the EU, for example, the fertility rate was 1.55 in 2018 (Anon., 2020). Many countries mitigate the effects of an aging population through immigration, providing them with human assets to boost the economy and care sector. While this is a sustainable arrangement for the developed world, this further exacerbates the potential effects of declining fertility rates in developing countries, as they are typically the countries that provide migrant workers to richer countries. For them, emigration results in loss of valuable human resources, further shrinking their workforce and tax base. Again, AI can compensate. AI offers countless ways to increase general productivity including:

- Analytics of crop data to help identify diseases, enable soil health monitoring and enhance the resilience of farming methods (IFC, 2020), resulting in more efficient food systems, yielding more produce and requiring fewer farmers.

- The provision of highly personalised healthcare via mobile phones (Houngbonon & Strusani, 2019), enabling widespread access to medical services with fewer trained doctors.

- Access to tailored tutoring via mobile learning platforms (UNESCO, 2019), allowing AI-based education to reach a much wider group, reducing the dependence on human teachers.

But AI can much more directly reduce anthropogenic impact on the environment. By harnessing the power of AI to, say, decipher trends in human behaviour, and weather and climate patterns, or to identify new materials to drive clean energy technologies, developing AI could be key to meeting the Paris climate targets.

Climate change and biodiversity loss are the biggest threats humanity has faced since its appearance on Earth seven million years ago. Immediate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, fertiliser usage and biodiversity loss are essential if humankind is to survive (Attenborough, 2020) – all impossible feats if population growth is not stalled. Education, specifically the education of women, could be the most powerful weapon conceivable when looking to prioritise the climate agenda and drive down fertility rates; whilst a growing implementation of AI is crucial in facilitating such significant change.

Bibliography

Anon., 2020. Africa’s population will double by 2050. The Economist, 28 March.

Anon., 2020. Fertility Statistics, s.l.: Eurostat.

Anon., n.d. Worldometer. [Online]

Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/japan-population/#:~:text=The%20median%20age%20in%20Japan%20is%2048.4%20years.

Attenborough, D., 2020. A Life on our Planet. 1 ed. London: Penguin Random House.

Booth, R., 2020. The Guardian. [Online]

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/sep/07/robots-used-uk-care-homes-help-reduce-loneliness

Corps, D., 2020. Births in England and Wales: 2019, s.l.: Office for National Statistics.

Criado-Perez, C., 2019. Invisible women: exposing data bias in a world designed for men. 1 ed. s.l.:Random House.

Dr Sahu, T. K. & Yadav, K., 2018. Women’s education and political participation. International Journal of Advanced Education and Research, November, 3(6), pp. 65-71.

Goetz, A. M., 2003. Women’s education and political participation, s.l.: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

Habtezion, S., 2016. Overview of linkages between gender and climate change, New York: United Nations Development Programme.

Hawken, P., 2017. Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming. 1 ed. s.l.:Penguin Books.

Hawken, P., 2020. The secret solution to climate change [Interview] (14 December 2020).

Houngbonon, G. V. & Strusani, D., 2019. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Supporting Development in Emerging Markets, s.l.: International Finance Corporation.

IFC, 2020. Artificial Intelligence in Emerging Markets, Washington, DC: IFC.

Kwauk, C., 2020. The secret solution to climate change [Interview] (14 December 2020).

Mahamed, F., Parhizkar, S. & Shirazi, A. R., 2012. Impact of Family Planning Health Education on the Knowledge and Attitude among Yasoujian Women. Global Journal of Health Science, March, 4(2), pp. 110-118.

Mavisakalyan, A. & Tarverdi, Y., 2019. Gender and climate change: Do female parliamentarians make difference?. European Journal of Political Economy, Volume 56, pp. 151-164.

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E., 2011. Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Global Environmental Change, October, 21(4), pp. 1163-1172.

Montoya, S., 2019. UNESCO.org. [Online]

Available at: http://uis.unesco.org/en/blog/data-celebrate-50-years-progress-girls-education

Mühleisen, M. & Faruqee, H., 2001. Japan: Population Aging and the Fiscal Challenge. Finance & Development, March.38(1).

Muoio, D., 2015. Business Insider. [Online]

Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/japan-developing-carebots-for-elderly-care-2015-11?r=US&IR=T

Nargund, G., 2009. Declining birth rate in Developed Countries: A radical policy re-think is required. Facts, Views & Vision, 1(3), pp. 191-193.

Pang, D. C., 2020. Explaining Humans. 1 ed. s.l.:Penguin.

Rolnick, D., 2019. Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, s.l.: s.n.

Schneider, T., Hong, G. H. & Le, A. V., 2018. Land of the Rising Robots. Finance & Development, June.55(2).

UN, 2017. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, s.l.: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

UN, 2019. World Population Prospects 2019, New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

UNESCO, 2011. Better Life, better Future: UNESCO Global Partnership for Girls’ and Women’s Education, Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO, 2011. Education counts: towards the Millennium Development Goals, Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

UNESCO, 2019. Mobile Learning Week 2019: Deciphering the impact of Artificial Intelligence on education, s.l.: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.