As Phoebe advises, do exercise caution when foraging, and research carefully the risks involved.

As cliché as it may sound, I’ve never really considered myself a ‘city girl’. Before moving to London, I lived in very rural areas, giving me an intense appreciation for the wonders of the natural world. I love the (albeit romanticised and unrealistic) concept of ‘living off the land’ and have always been fascinated by the practical uses and applications of wild plants. Despite living in London, one of the most urban areas in Britain, I try to nurture this interest of mine, primarily through foraging.

Foraging is defined as ‘searching widely for food or provisions’. Upon hearing the word, I won’t blame you for picturing a Bear Grylls-wilderness-survival-type situation, we usually use the term in a much wilder context. But, unbeknownst to the average passer-by, London is absolutely teeming with naturally abundant, forgeable plants- often disguised as ‘weeds’ or unkept undergrowth. So, as someone who has been harvesting teas, cordials, dyes, and inks over the past few years using uncultivated plants from their local area, I’d love to introduce you to a few tips and tricks vital to the art of foraging in the concrete jungle:

- Know your legislation

While London is brimming with forgeable plants provided you know where to look, there are some places you really shouldn’t look. The Theft Act (1968) states:

‘(3)A person who picks mushrooms growing wild on any land, or who picks flowers, fruit or foliage from a plant growing wild on any land, does not (although not in possession of the land) steal what he picks, unless he does it for reward or for sale or other commercial purpose.’

Basically, as long as you avoid cultivated (deliberately grown) plants, for example a flower bed in a park, you’re in the clear. I also haven’t come across any legislation which specifically protects ‘Council maintained land’- e.g., parks and commons- from foraging.

That said, it is illegal to ‘interfere with any plant or fungus’ within the Royal Parks – unless you have ‘the Secretary of State’s written permission’, of course. There are eight Royal Parks in London: Hyde Park, Kensington Gardens, Richmond Park, Bushy Park, St. James’ Park, Green Park, Regent’s Park, Greenwich Park, Brompton Cemetery, and Victoria Tower Gardens.

Additionally, some specific boroughs forbid foraging (e.g., Wandsworth council) in local parks to avoid any upset of the ecosystem. But, providing you avoid these spaces and only take truly uncultivated plants and do so respectfully and in moderation, you should be well on the right side of the law.

2. Err on the side of caution when looking for food

This may seem like common sense, but if you’re planning to forage for foodstuff, be extremely sure you know what you’re looking for. Be aware of any possible inedible lookalikes and know which parts of a certain plant are edible (e.g., elderflowers are a common and versatile forgeable, but the leaves, stalks and roots of the plant are toxic if consumed). Basically, if you’re at all unsure about what it is that you’re picking, don’t put it in your mouth. Additionally, be aware of where you’re picking from. When looking for something I plan to consume, I try to avoid especially polluted areas. If somewhere is right by a roadside and absolutely covered in litter, you may be better off looking elsewhere. Also, be very wary of things growing at ‘dog-pee’ height- particularly along pathways. Where possible, collect from 0.5-1 metres above ground level and a little away from main pathways. Making food with hand-forged ingredients is such a special experience, and one I encourage you to try, but just be cautious.

3. Familiarise yourself with plants in your local area and their properties

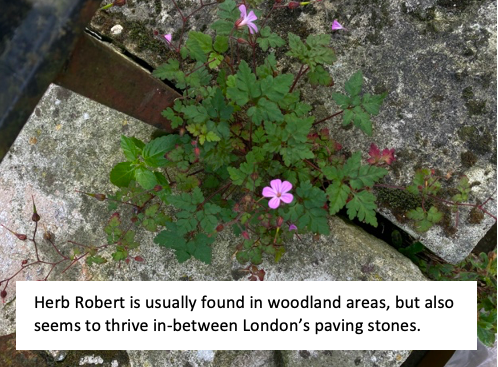

Building up a mental inventory of what grows where within your local area is one of the most useful tips that I can give you. Start learning to identify individual plants, including their properties and uses. By just keeping an eye out when out and about, you can build up a solid mental map of where to find specific plants. It may seem like an overwhelming task, but by learning a few new plants every week or so, you’ll be amazed by how quickly your knowledge improves. Plus, in the age of smartphones, identifying new plants literally couldn’t be easier- most plant ID apps allow you to upload a photo of the plant, then provide a detailed identification. From there, a quick Google search can lead to any practical uses the plant has. Don’t rule anywhere out! A few months ago, I discovered a thriving patch of lemon balm (one of my favourite tea herbs) growing in between two paving stones inside East Putney Station. Though I wouldn’t recommend using a tube station as a source of tea, it’s still useful information to have.

4. Be seasonal!

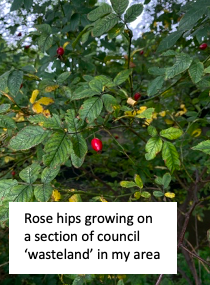

Plant stock and variation differs greatly depending on the season. Lean into this rather than searching in vain for something that’s no longer seasonal and will be much harder to find. Also, don’t think that because days are getting shorter and colder, the time for foraging is over. Rose hips (a delightful autumnal forgeable) are only just arriving! They can be used to make anything from tea, to dye, to cosmetic oil.

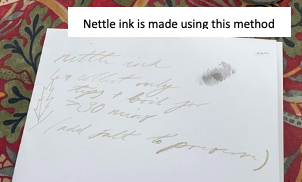

Helpful seasonal indicators can be used to keep track of the seasons. Indicators include: violets in early spring (a multi-purpose flower used for anything from syrup to ink), elderflowers in early midsummer (for that classic cordial), blackberries in late summer (which make a cracking jam but can also be eaten as they are), and acorns throughout autumn (these can be used to make a flour substitute, but they also produce a wonderful deep dye/ink). That said, there are also many marvellous year-round forgeable plants, such as chickweed (which can be used in salads and sauces) and nettles (nettle tea is a favourite of mine, but I’ve also made some great inks with it).

5. If in doubt, boil it.

Firstly, I highly recommend plant-specific research when foraging. If you have a particular product in mind, find out as much as possible about how to make it, including other factors that may affect the final result. That said, if all else fails, pretty much anything can be made from foraged plants by simmering them in water. This is how I make rose water and teas, but also dyes and inks, and even syrups, cordials, and jams.

If you’re trying to infuse an oil (e.g., to make rosemary hair oil), cover the plants with a base oil and heat at mid-temperature for half an hour or so (you’ll be able to smell it when it’s done). Though I do very much encourage specific research, often products require an extract sourced from simmering the plant in water.

Above all, my biggest golden rule of foraging (especially in urban areas) is to not take anything that’s absence will be noticed. If a passer-by is going to be able to tell that something was taken from that spot, then leave it well alone. Nature is for everyone, and we must be especially respectful of it in places such as London, where wild areas are so few and far between. Though there is something truly magical in writing with ink that you have hand collected and crafted yourself, it is absolutely no justification for depriving other people of the natural world and its gifts. With that in mind, happy foraging!