By Helena Rees, Head of Maths.

Many still see people who are good at maths as slightly weird, geeky, uncool. Why is this? Why should we study maths?

A couple of years ago Professor Brian Cox hosted ‘A Night with the Stars’ on the BBC. From the lecture theatre of the Royal Institution, he undertook to explain among other things how diamonds are made up of nothingness and how things can be in an infinite number of places at once. He took the audience, made up of famous faces, celebrities and scientists, through some of the most challenging concepts in physics, using maths and science experiments as he went along. It was a truly fascinating programme and if nothing else demonstrated the power of numbers and the speed with which they can make a grown man cry. Jonathan Ross (43 mins approx) was invited to assist Brian Cox in a maths calculation using standard form. The look of sheer panic on Ross’s face, followed by him saying, “This is the worst thing that’s happened to me as an adult” and “I’m sweating”, just about sums up many people’s attitude towards maths.

Mrs Duncan spoke to the whole school this week and used this example. Imagine going out for dinner with six friends and the bill comes. When the time comes to split the bill between seven, the bill is shuffled to the maths teacher or accountant with a slightly shame-faced look saying, “I am rubbish at maths” or “I couldn’t do maths at school”. Imagine, however, that same group of people sitting down to order and someone asking for the menu to be read out because they can’t read it. Few will admit that they can’t read as the stigma of this would be hugely embarrassing. Yet no such reservations exist for maths with individuals almost boasting about their lack of maths ability. Why is this?

Many still see people who are good at maths as slightly weird, geeky, uncool. A PhD in Maths or Physics at the end of a name tends to conjure up images of social awkwardness — people more to be pitied. On the whole surveys of attitudes over the past 50 years have shown that the cultural stereotype surrounding ‘scientist and mathematician’ has been largely consistent — and negative. However, things are changing, in November 2012, President Obama held a news conference to announce a new national science fair. “Scientists and engineers ought to stand side by side with athletes and entertainers as role models, and here at the White House, we’re going to lead by example,” he said. “We’re going to show young people how cool science can be.” The idea that scientists, mathematicians and engineers could attain iconic status is exciting.

The popularity of television shows such as ‘Think of a Number, ‘Countdown’ and more recently the use of numbers in ‘Numb3rs’, and ‘How Do They Do That?’ have boosted the public’s perception of Maths. CSI has done more for boosting number of students of forensic science than any careers fair. The Telegraph recently reported that students who had a Maths A Level earned on average £10,000 more than a student without. Perhaps statistics like these would encourage more students to take the subject seriously. A report by think-tank Reform estimates that the cost to the UK economy between 1990 and 2008 of not producing enough home-grown mathematicians was £9 billion, such is the value of maths expertise to business.

Marcus du Sautoy, second holder of the Charles Simonyi Chair in the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Oxford says he can’t understand the pride there is in being bad at Maths. “It’s bizarre why people are prepared to admit that because it’s an admission that you can’t think logically. Maths is more than just arithmetic. I would rather do business with someone who admits they’re good at Maths. You don’t get that in the Far East. In Korea or China they’re really proud of being good at Maths because they know the future of their economies depend on it, their finances depend on it. Mobile phones, the internet, Playstations and Google all depend on Maths,” he says. “If people realised that, then they wouldn’t poke fun at it so easily. In today’s information age, Mathematics is needed more than it ever was before – we need Maths. Problem solving skills are highly prized by employers today. There is an increasing need for Maths and the first step needed is a change in our attitudes and beliefs about Maths.”

It is true that many of us will not do another quadratic equation or use trigonometry in our daily lives. However, Mathematics is more than just the sum of subject knowledge. The training to become a scientist or an engineer comes with a long list of transferable skills that are of enormous value in the ‘outside world’. Communication skills, analytical skills, independence, problem-solving skills, learning ability — these are all valuable and at the top of Bloom’s taxonomy. But scientists, mathematicians and engineers tend to discount these assets because they are basic requirements of their profession. They tend to think of themselves as subject-matter experts rather than as adaptable problem solvers.

We have all heard of Pythagoras and his famous theorem. The theorem states that the sum of the squares on the two shorter sides of a right angle triangle sum to the square on the hypotenuse, more commonly shortened to a2 + b2 = c2. In 1637 Pierre de Fermat postulated that no three positive integers a, b, and c satisfy the equation an + bn = cn for any integer value of n greater than 2. For example to a3 + b3 = c3 After his death, his Fermat’s son found a note in a book that claimed Fermat had a proof that was too large to fit in the margin. It was among the most notable theorems in the history of mathematics and prior to its proof, it was in the Guinness Book of World Records as the “most difficult mathematical problem”.

(https://plus.maths.org/content/fermats-last-theorem-and-andrew-wiles ) However, in 1994 Andrew Wiles, published a proof after 358 years of effort by Mathematicians. The proof was described as a ‘stunning advance’ in the citation for his Abel Prize award in 2016. You can watch an interview with Andrew Wiles by Hannah Fry where he was interviewed this week in the London Public Lecture Series organised by Oxford University.

In a recent article Wiles commented “What you have to handle when you start doing Mathematics as an older child or as an adult is accepting the state of being stuck. People don’t get used to that. They find it very stressful.” He used another word, too: “afraid”. Even people who are very good at Mathematics sometimes find this hard to get used to. They feel they’re failing. “But being stuck, isn’t failure. It’s part of the process. It’s not something to be frightened of. Then you have to stop. Let your mind relax a bit…. Your subconscious is making connections. And you start again—the next afternoon, the next day, the next week.”

Patience, perseverance, acceptance—this is what defines a Mathematician.

Hilary Mantel, novelist and writer of Wolf Hall writes “If you get stuck, get away from your desk. Take a walk, take a bath, go to sleep, make a pie, draw, listen to music, meditate, exercise; whatever you do, don’t just stick there scowling at the problem. But don’t make telephone calls or go to a party; if you do, other people’s words will pour in where your lost words should be. Open a gap for them, create a space. Be patient” Perhaps Mathematicians and novelists are so different after all?

When it comes to Mathematics people tend to believe that this is something you’re born with, and either you have it or you don’t and this is the common refrain at parents evenings. But that’s not really the experience of Mathematicians. We all find it difficult. It’s not that we’re any different from someone who struggles with Mathematics problems in junior school…. We’re just prepared to handle that struggle on a much larger scale. We’ve built up resistance to those setbacks. A common comment on parents evening is to delegate the Maths homework to dad as that is ‘his thing’. What message does this give our girls of today? That this is a subject that boys are good at.

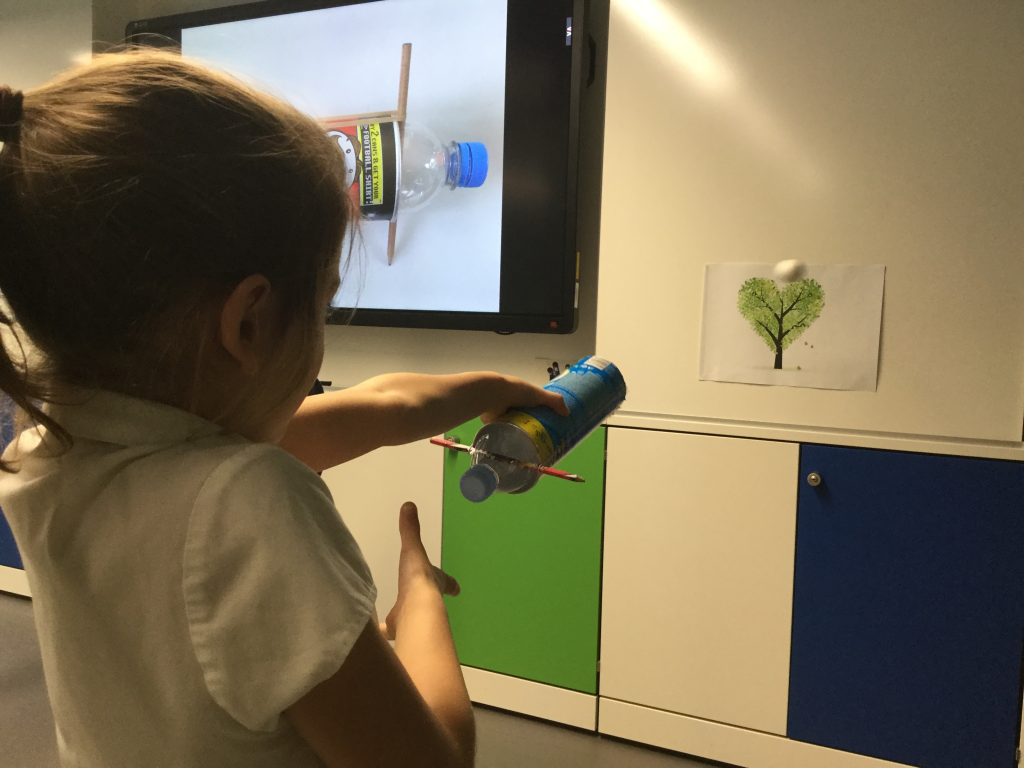

Luckily for us here at Wimbledon High School we have a strong culture of doing well in Maths. We have excellent results at iGCSE and there are over 50 girls this year in year 12 alone studying some form of post 16 Mathematics qualification with a view to a STEM career. The new Steam room is an exciting initiative to be part of. A recent article in the National Centre for the Excellence in Teaching of Mathematics journal, asked how can we get more girls to study A Level Maths. The answer at WHS? Keep doing what we are doing well and continue to be excited and positive about the beauty and the magic of numbers.

At school, I lead the annual trip for students in Year 10 – Year 13 to Poland, where we visit Auschwitz concentration camp and Oskar Schindler’s factory. When he died, Oskar Schindler asked to be buried in Jerusalem, facing the Mount of Olives and his grave is visited by millions each year. On my second day, I searched for his grave. In a way, it was closing a circle. I had visited his factory in Poland, listened to many Schindler survivor testimonies and, of course, watched the film. Here was my opportunity to pay tribute to that awe-inspiring man, who saved so many. His grave had stones placed on top of it, a Jewish tradition to honour the dead. Later in the week, I visited Yad Vashem, the Israeli memorial to the Shoah (Holocaust) and saw his tree planted in the ‘Avenue of the Righteous’ – a row of trees placed in memory of all the non–Jews who helped save the lives of Jewish people during the Shoah.

At school, I lead the annual trip for students in Year 10 – Year 13 to Poland, where we visit Auschwitz concentration camp and Oskar Schindler’s factory. When he died, Oskar Schindler asked to be buried in Jerusalem, facing the Mount of Olives and his grave is visited by millions each year. On my second day, I searched for his grave. In a way, it was closing a circle. I had visited his factory in Poland, listened to many Schindler survivor testimonies and, of course, watched the film. Here was my opportunity to pay tribute to that awe-inspiring man, who saved so many. His grave had stones placed on top of it, a Jewish tradition to honour the dead. Later in the week, I visited Yad Vashem, the Israeli memorial to the Shoah (Holocaust) and saw his tree planted in the ‘Avenue of the Righteous’ – a row of trees placed in memory of all the non–Jews who helped save the lives of Jewish people during the Shoah.