Mrs Clare Duncan, Director of Studies at WHS @MATHS_WHS, describes the Harkness approach she observed at Wellington College and the impact that this collaborative approach has in the understanding of A Level Maths.

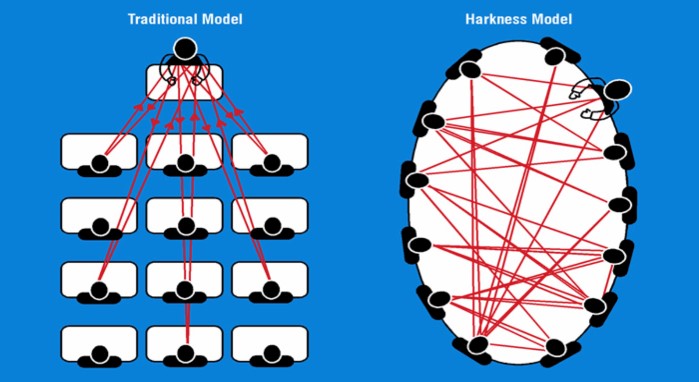

Named after its founder, Edward Harkness, Harkness it is a pedagogical approach that promotes collaborative thinking. Edward Harkness’ view was that learning should not be a solitary activity instead it would benefit from groups of minds joining forces to take on a challenging question or issue. What Harkness wanted was a method of schooling that would train young people not only to confer with one another to solve problems but that would give them the necessary skills for effective discussion. Harkness teaching is a philosophy that began at Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire in the 1930s.

Edward Harkness stated:

“What I have in mind is [a classroom] where [students] could sit around a table with a teacher who would talk with them and instruct them by a sort of tutorial or conference method, where [each student] would feel encouraged to speak up. This would be a real revolution in methods.”

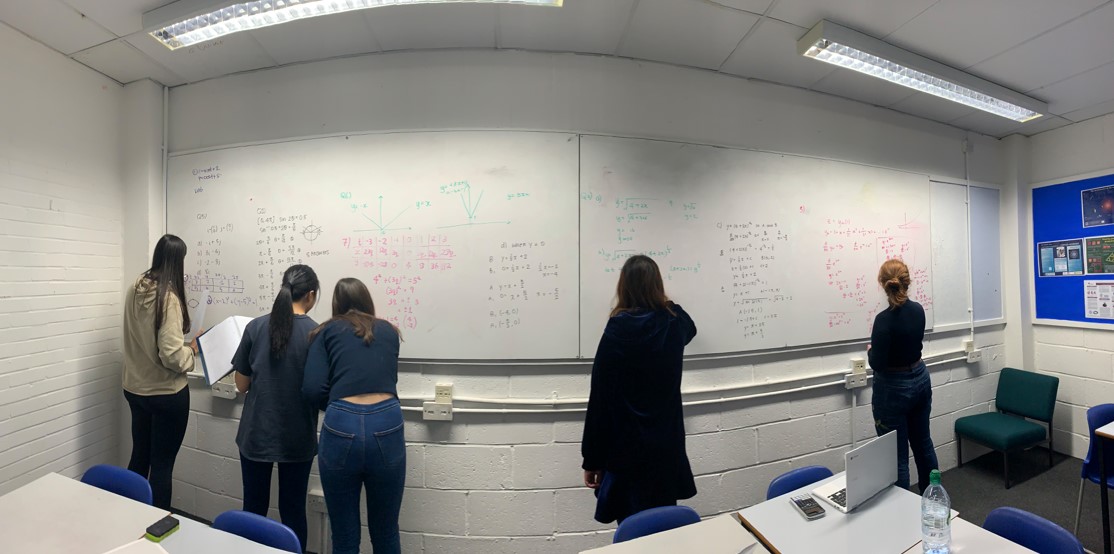

This was very much what the classroom looked like when I was lucky enough to observe Maths teaching at Wellington College last term. Their newly refurbished Maths rooms had floor to ceiling whiteboards on all the walls. On entering the classroom, the students were already writing their solutions to problems that were set at preparatory work for the lesson. Whether the solution was correct or not was irrelevant, it was a focal point which allowed students to engage in discussion and offer their own views, problems and suggestions. The discussion was student led with the teacher only interjecting to reinforce a significant Maths principle or concept. The key learning point is giving the students their own time before the lesson to get to grips with something before listening to the views of others.

The Maths teachers at Wellington College have developed their own sets of worksheets which the students complete prior to the lesson. Unlike conventional schemes of work, the worksheets follow an ‘interleaving’ approach whereby multiple topics are studied at once. Time is set aside at the start of the lesson for students to put their solutions on whiteboards, they then walk around the room comparing their solutions to those of others. Discussion follows in which students would discuss how they got to their answers and why they selected the approach they are trying to use. In convincing others that their method was correct, there was a need for them to justify mathematical concepts in a clear and articulate manner. The students sit at tables in an oval formation, they can see one another and no-one is left out of the discussion. The teacher would develop the idea further by asking questions such as ‘why did this work?’ or ‘where else could this come up?’.

The aim of Harkness teaching is to cultivate independence and allows student individual time to consume a new idea before being expected to understand it in a high-pressured classroom environment. This approach can help students of all abilities. Students who find topics hard have more time than they would have in class to think about and engage with new material and students who can move on and progress are allowed to do so too. In class, the teacher can direct questioning in such a way that all students feel valued and all are progressing towards the end objectives. It involves interaction throughout the whole class instead of the teacher simply delivering a lecture with students listening. It was clear that the quality of the teachers questioning and ability to lead the discussion was key to the success of the lesson.

Figure 1: WHS pupils in a Maths lesson solving problems using the Harkness approach

This was certainly confirmed by my observations. The level of Maths discussed was impressive, students could not only articulate why a concept worked but suggested how it could be developed further. I was also struck by how students were openly discussing where they went wrong and what they couldn’t understand; a clear case of learning from your mistakes. Whenever possible the teaching was student led. Even when teachers were writing up the ‘exemplar’ solutions, one teacher was saying ‘Talk me through what you want me to do next’. Technology was used to support the learning with it all captured on OneNote for students to refer to later. In one lesson, a student was selected as a scribe for notes. He typed them up directly to OneNote; a great way of the majority focusing on learning yet still having notes as an aide memoir.

Although new to me, at Wimbledon we have been teaching using the Harkness approach to the Sixth Form Further Maths students for the past couple of years. Having used this approach since September it has been a delight to see how much the Year 12 Further Maths pupils have progressed. Being able to their articulate mathematical thinking in a clear and concise way is an invaluable skill and, although hesitant at first, is now demonstrated ably by all the students. The questions posed and the discussions that ensue take the students beyond the confinements of the specifications.

–

As the lessons progressed, I started enjoying this method of teaching as it allowed me to understand not only how each formula and rule had come to be, but also how to derive them and prove them myself – something which I find incredibly satisfying. I also particularly like the fact that a specific problem set will test me on many topics. This means that I am constantly practising every topic and so am less likely to forget it. Also, if I get stuck, I can easily move on to the next question.

As the lessons progressed, I started enjoying this method of teaching as it allowed me to understand not only how each formula and rule had come to be, but also how to derive them and prove them myself – something which I find incredibly satisfying. I also particularly like the fact that a specific problem set will test me on many topics. This means that I am constantly practising every topic and so am less likely to forget it. Also, if I get stuck, I can easily move on to the next question. Moreover, I very much enjoyed seeing how other people completed the questions as they would often have other methods, which I found far easier than the way I had used. The other benefit of the lesson being in more like a discussion is that it has often felt like having multiple teachers as my fellow class member have all been able to explain the topics to me. I have found this very useful as I am in a small class of only five however, I certainly think that the method would not work as well in larger classes.

Moreover, I very much enjoyed seeing how other people completed the questions as they would often have other methods, which I found far easier than the way I had used. The other benefit of the lesson being in more like a discussion is that it has often felt like having multiple teachers as my fellow class member have all been able to explain the topics to me. I have found this very useful as I am in a small class of only five however, I certainly think that the method would not work as well in larger classes.

Both music and languages share the same building blocks as they are compositional. By this, I mean that they are both made of small parts that are meaningless alone but when combined can create something larger and meaningful.

Both music and languages share the same building blocks as they are compositional. By this, I mean that they are both made of small parts that are meaningless alone but when combined can create something larger and meaningful. But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing.

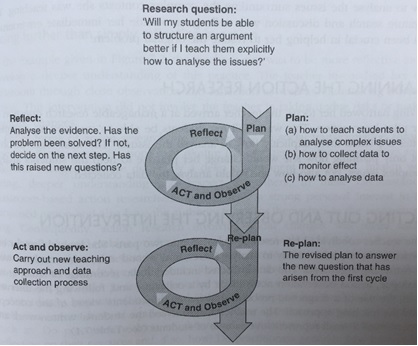

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing. Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.

Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.