Spring Focus: Metacognition – Computer Science Skills

In this gem, I will be looking at the thinking skills that are taught as part of the Computer Science Curriculum and the ways in which they are taught. I hope that by sharing our ideas, we can start to think of problem solving as a set of skills involved across a range of subjects.

Metacognition skills are key to the study of computer programming. When encountering a new task, novice computer programmers are likely to concentrate on the superficial details of the problem, failing to break it down into manageable sub tasks and trying to solve the whole problem in one go. We often see this in our lessons and I’d be really interested to hear if any other colleagues encounter similar issues or use similar skills in their subjects.

Metacognition Skill 1: Decomposition

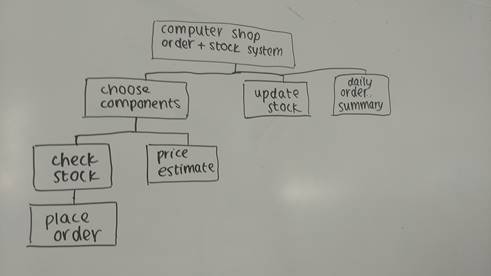

Decomposition is the process of breaking a large problem down into progressively smaller “chunks”, making it easier to solve. By the time they complete the GCSE course, students should be comfortable with these steps. In order to promote this at GCSE, students develop this skill in three ways:

|

At the start of the course: After introducing the concept of decomposition, students are asked to create an overview of the parts of their favourite board game. This gets them to take an algorithm (set of steps, as defined by the rules) and gets them to think about them in a different way. |

|

Further on in their learning, the class will be asked to attempt a decomposition diagram, working collaboratively to spot the key components of the problem. This work is not marked, nor do they have to follow a set format; it simply acts as their plan for the task. |

|

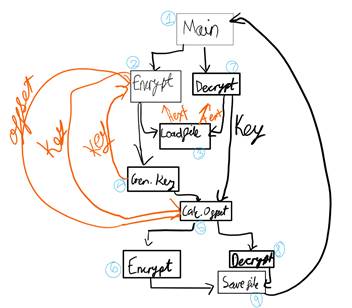

Finally, at the end of a project, the class is given a solution prepared by the teacher. Their task is then to reverse-engineer the decomposition diagram, so that they can follow the thought process used and begin to do it by themselves in the future.

|

Metacognition Skill 2: Abstraction

Abstraction is the skill of removing unnecessary detail, allowing the programmer to focus on the important parts of the problem. A famous example of this is tube map, where Harry Beck realised that the geographical positions of the tube stations was unimportant; his map focused more on the order of stations and highlighting interchanges, using approximate locations (click here for a geographically accurate tube map and see how much hared it is to follow).

In this activity, students are paired, with one partner blindfolded. The partner who can see is given a photograph (of a bird, for example) and has to get the blindfolded “artist” to recreate the picture as accurately as possible. The results are often comical, occasionally hilarious and always excite some sort of comment. After a couple of iterations, the class is asked to reflect and discuss how they made it easier to describe the image to their partner. Many of them will respond with ideas such as “I told her to draw a circle the size of a 10p” and this can lead us in to the concept.

Metacognition Skill 3: Mental Mapping

In creating larger software projects, it’s important to consider how users will interact with the solution; the user will create a mental map of software, giving them an idea of where they are, where they need to go and the way back to the beginning. The class are asked to close their eyes and count the number of windows in their house (some of the numbers shocked me when I first asked this in a private school). After asking for their responses and writing them on the board, they are asked to forget about the number and to describe the process they went through. Were they inside or outside? Which room did they start in if they were inside? Did they fly around the outside? This allows us to explore the idea that they have a mental model or map of their house in their heads. This can be broadened out into directions to their nearest train station or supermarket. Then we look at the steps involved in performing everyday computer tasks, such as writing a letter in Word. Using these examples, the students then design their solution.

Why these ideas are Useful…

- By introducing the skill in a non-technical and familiar situation to begin with, we can avoid overwhelming the pupils with new terminology

- Instead of this being something new that the students feel they have to acquire, we can give them the idea that these are skills that they already possess and with practice can develop

- It allows them to develop their confidence in the face of unknown problems and to draw out the similarities between tasks

- Although these are Computer Science examples, they can be applied to other subjects:

-

- Planning a project or research by splitting it into easy to achieve tasks

- Describing concepts to others in a simple and concise way

- Designing the layout of anything